On the imperative of engaging citizens in innovation policies

In an era where the urgency to transition our economies and societies towards environmentally sustainable and inclusive models is widely recognised, it is more important than ever for governments to engage in dialogues with citizens. Tackling the climate crisis does not only require major technological progress but changes in our daily lives, including in transportation and consumption modes. Moreover, the rise of artificial intelligence and automation transforms societies in fundamental ways, including by shaping employment options and affecting the nature of social interactions. Discussing innovation policy with citizens consequently matters to ensure technological progress builds desired futures.

However, according to the OECD Trust Survey, few people see opportunities to participate in policymaking. To foster a more inclusive and democratic approach to policymaking and bolster public trust in government, it is imperative for governments to proactively implement measures that encourage citizens to participate in public decision-making.

Modalities of engagement span from citizen assemblies and juries, scenario workshops, focus group discussions and urban innovation labs. As an illustration, Norway’s Board of Technology employs a combination of scenario workshops, focus group discussions, and public polls to gather insights from citizens and stakeholders regarding new transportation technologies. In the United Kingdom, the Climate Assembly UK held in 2020 engaged about 100 randomly selected citizens to develop jointly with experts recommendations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the country. Similar initiatives have been held in many other countries including Austria, France, Denmark and Germany. The Citizen Innovation Lab in Limerick, Ireland aims to empower city dwellers to take part in co-creating a climate-neutral city by 2050, and includes a Citizens’ Observatory, an Engagement Hub, a digital platform, and a programme of events.

A recently released OECD report delves into engaging citizens in innovation policymaking, building on the OECD Guidelines for citizen participation processes. The exploration is not merely about the “why” but also addresses the “when” and “how”. In this blog, we sketch some of its findings and insights.

Why engage citizens?

Engaging citizens in innovation policy has the following returns:

- Increasing the quality of policies. Decisions are affected by the perspectives of those taking them, as historically illustrated by the case of gender bias in medical research. Engaging with citizens brings a myriad of policy-relevant ideas, information, and resources to the table. This participatory approach mitigates potential biases inherent in policy decisions. When diverse perspectives are considered, the outcomes are more comprehensive and reflective of a broader societal spectrum.

- Designing policies that prioritize societal needs and fully consider their extensive socio-economic implications. Consider the implications of AI on employment or how offshore wind farms might reshape landscapes. By collaboratively setting policy directions, it is possible to anticipate and address potential concerns, thereby minimizing resistance to change. Such an approach is also essential to understand the varied impacts policies might have on different segments of the population, as illustrated by the contrasting effects of fuel carbon taxes on urban and rural households. This paves the way for appropriate compensatory measures, ensuring transitions are equitable and inclusive.

- Enhancing trusted government-citizen connections: Building stronger connections between citizens and government officials is pivotal for fostering trust in government. Consequently, engagement processes that facilitate the direct interaction between government representatives and civil servants and the citizens they serve can be highly effective. These interactions help reduce the perceived “distance” between citizens and public sector officials, making government more relatable and approachable for the people it serves.

- Enhancing positive technological progress: The full potential of technological advancements is realized when these innovations are widely adopted and integrated into society. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a stark example of suboptimal uptake of solutions, such as contact-tracing apps and vaccines, underscoring that uptake requires citizen endorsement. Public engagement is consequently central to advancing technological progress.

When to engage citizens?

As is often the case, quality over quantity. Policymakers should give priority to organising limited, yet well-designed and more impactful engagement processes, rather than multiplying processes as a “tick-the-box” formality, which may end up disappointing participants and increase mistrust in government.

Engagement is most relevant when any of these three conditions are met:

- Decisions on long-term policy directions among a diversity of possible pathways that require societal endorsement. These may involve value judgements, important trade-offs and significant costs in the short term, while benefits may only be reaped in the longer term.

- Policies requiring local community knowledge and inputs for their success. Citizens are the most knowledgeable about dynamics and challenges that affect their everyday lives in their communities. Their perspectives can critically inform innovation programmes aimed at responding to specific community needs (e.g. addressing public transportation challenges in a specific region), and be an important complement to experts’ perspectives.

- Policy topics citizens deeply care about, that possibly create divides between “winners” and “losers”. The areas citizens deeply care about are important for engagement where they risk polarising societal debates, including on social media. It is also essential to address issues that negatively impact certain segments of the population. For instance, industrial transitions can affect regions specialised in declining industries and those employed by them, while benefiting the rising sectors. In recent years many public dialogues have focused on the impacts on society of advances in the fields of data, artificial intelligence and robotics, voicing public concerns about the unequal distribution of benefits and risks of such advances.

How to engage citizens?

Implementing such processes will only succeed if they are well-designed around the following issues:

- Tailor outreach processes to involve a wide diversity of citizens beyond those that are already interested in the topic or have stakes in the decisions, including special means to engage underrepresented groups in STI spheres. This can be achieved by building engaging and inclusive narratives (stories about why a policy issue is relevant and how it will benefit society), recruiting “trusted voices” (e.g. community leaders, academics from a local university) to effectively connect to communities that feel more distant from government, and leveraging the press and social media.

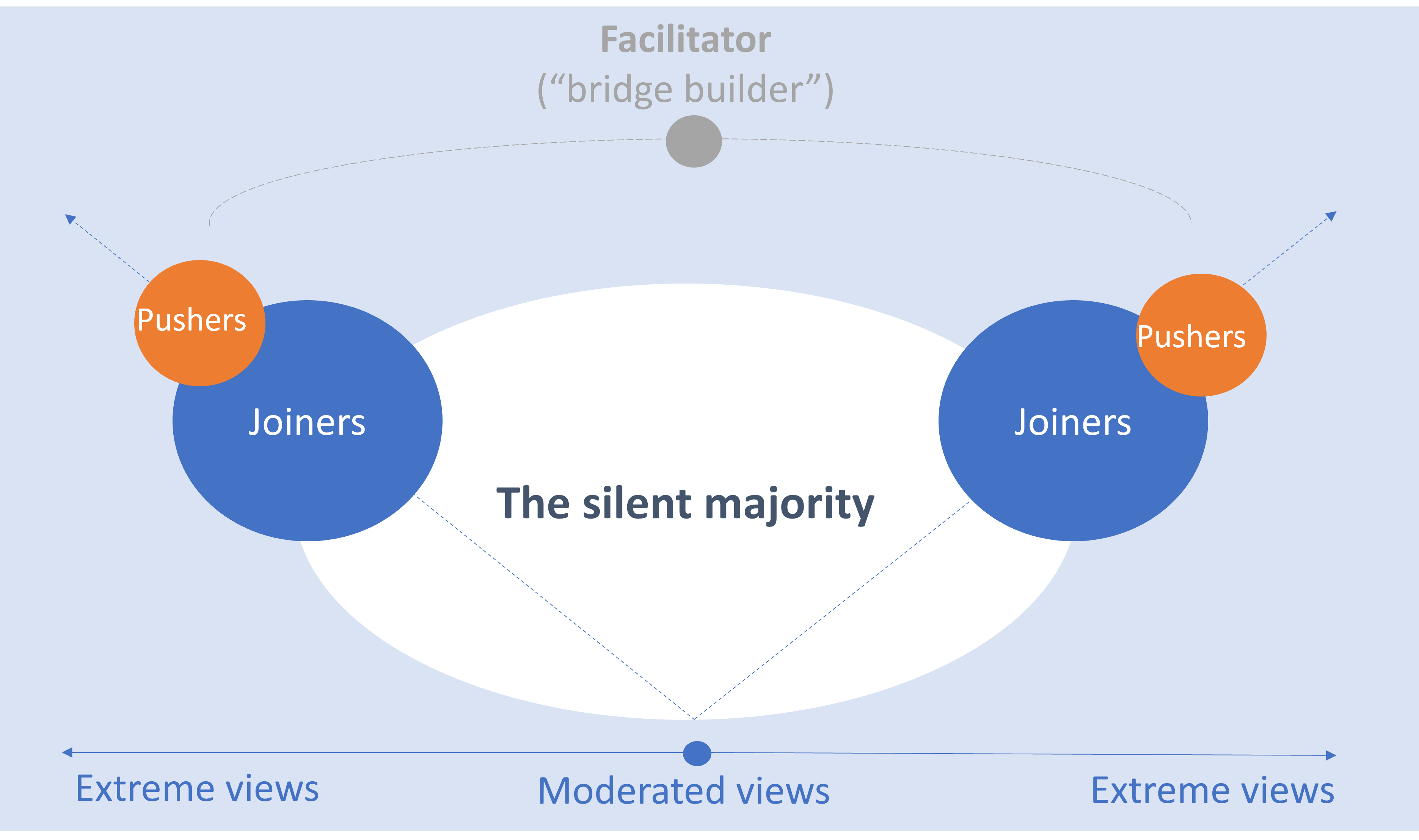

- Create a level-playing field for all participants to express their views and avoid polarisation of debates. It is critical to prevent that ‘louder voices’ (which are often those with more extreme views, see Figure 1) dominate the process and have an excessive influence on its results. This can be achieved by setting up discussion prior to citizens having formed strong opinions, engaging neutral and trustworthy facilitators, using neutral spaces for discussions, and devising methods for dealing with divergent (and sometimes polarised) perspectives.

- Integrate inputs from citizens in the policy process and communicate to participants (and the public) how their inputs were used and how they shaped the policy process. This can help to ensure that citizen inputs are not solicited as a mere formality, but are actually integrated into the policy-making process. It can also help to increase citizen awareness and support for innovation policies aimed at advancing societal goals, and enhance trust in the government and the public administration.

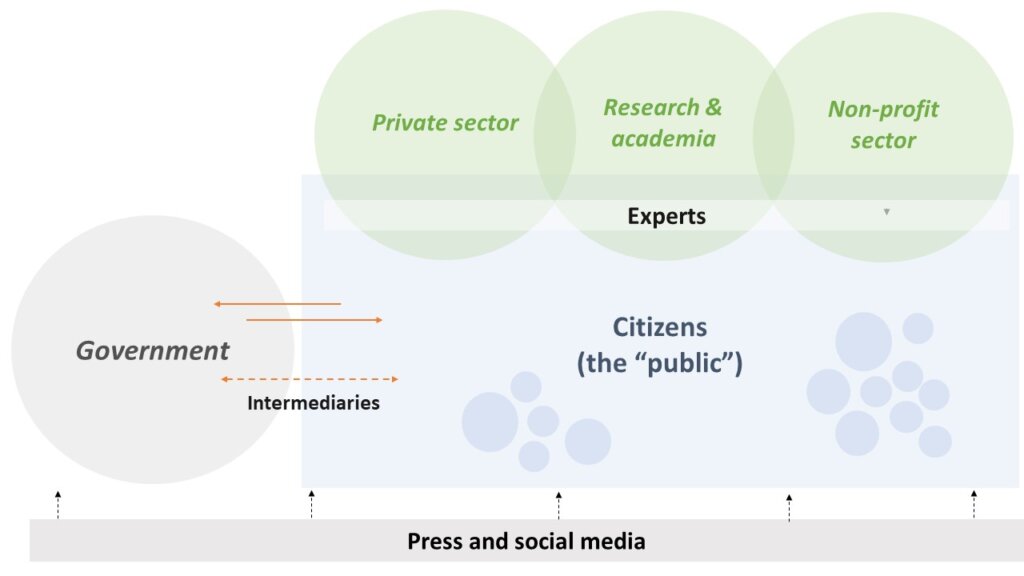

- Organise citizen engagement in complementarity to policy consultation processes and with other stakeholders, including experts and industry stakeholders. While experts and stakeholders provide specialized insights rooted in years of experience, citizen engagement ensures policies resonate with the broader public’s needs and aspirations. As illustrated in Figure 2, in some cases, experts and industry stakeholders also contribute to citizen engagement processes (e.g. as providers of different perspectives to inform the process). In those cases, it is important that their involvement is carefully calibrated to prevent any undue influence or bias.

- Finally, it’s crucial for engagement processes to align design choices with their specific objectives. These design considerations, such as choosing between in-person or online formats, selecting appropriate tools, determining the level of orchestration, specifying the number of interactions, and outlining expected outcomes, should be tailored to the unique purpose and context of the participatory initiative. For instance, when the aim is to elicit perspectives from minority groups that may be hesitant to engage with government, in-person smaller group discussions prove indispensable, as online formats are less likely to facilitate their active participation.

Find out more in: Paunov, C. and S. Planes-Satorra (2023), “Engaging citizens in innovation policy: Why, when and how?”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 149, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ba068fa6-en.