Fixing frictions: ‘Sludge audits’ around the world

How governments are using behavioural science to reduce psychological burdens in public services

Ever had to sit through long wait times without any update on where you are in the queue? How about spending hours applying to a government programme without knowing if you are eligible? These are both prime examples of ‘sludge’ in government services and processes. Sludge consumes significant time and resources, contributes to frustration and distrust, and jeopardises equitable access to government services.

The OECD’s Fixing frictions: ‘Sludge audits’ around the world policy paper puts forward nine good practice principles to support governments in reducing “sludge”, defined as unjustified frictions that create barriers for people when accessing a service or completing a process.

The paper presents ten case studies from the first International Sludge Academy – a joint initiative of the OECD and the Government of New South Wales (NSW) in Australia – in which 16 governments from 14 countries independently conducted ‘sludge audits.’ A sludge audit is a structured behavioural assessment of a service or process, aiming to identify, prevent and reduce unnecessary frictions and psychological costs which affect effectiveness and accessibility of the service.

What do we mean by ‘psychological costs’?

- Search costs: occur when people are searching for information about a process but encounter barriers due to outdated information, unclear language or confusing requirements.

- Decision costs: occur when people are asked to evaluate options, especially when differences between them are unclear due to ambiguous eligibility criteria and choice overload.

- Cognitivie costs: are the mental resources people spend on fulfilling requirements including understanding complex information or contacting support for clarity when instructions are unclear.

- Emotional costs: can occur throughout a process. These include encountering stigma, experiencing a loss of autonomy, or feeling stressed, disempowered, anxious, confused or frustrated.

The report includes ten case studies of successful sludge audits by governments from around the world. By employing a behavioural lens, sludge audits build upon and enhance traditional burden reduction approaches through an analysis of the psychological costs that people experience while trying to access a service or process.

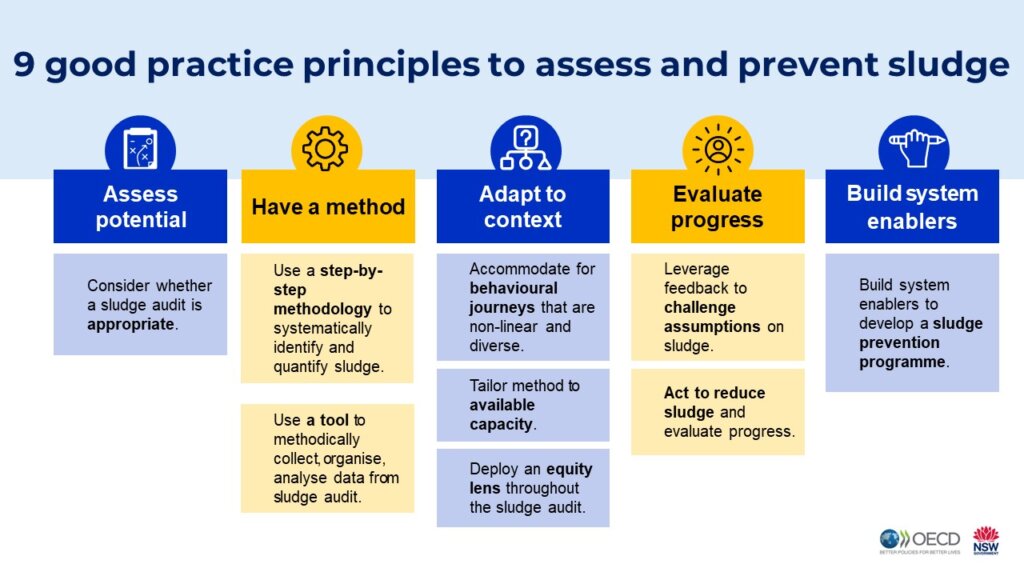

Nine Good Practice Principles for reducing sludge

The experience of teams that participated in the International Sludge Academy suggests nine good practices for organisations implementing sludge reduction initiatives:

- Consider whether a sludge audit is appropriate. Institutional context and available resources are essential to consider when committing to a sludge audit. Decision matrices can enable teams to make informed decisions about whether to conduct a sludge audit.

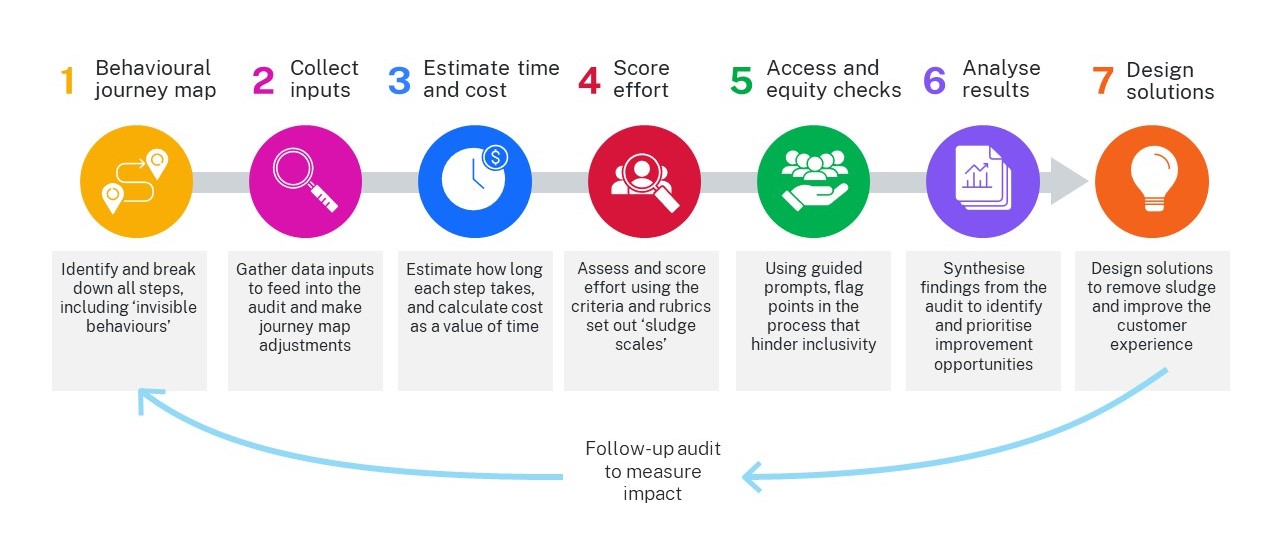

- Use a step-by-step methodology to systematically identify and quantify sludge. Pre-defined methodologies that have been tested in various contexts offer several advantages including rigour, replicability and comparability, and access to experience. Try out the NSW method here.

- Tailor the sludge audit methodology to available capacity. Sludge audits can be conducted by diverse types of teams. While behavioural science and customer experience expertise can be advantageous, it is not necessary to conduct an audit. Teams without behavioural science or customer experience expertise will benefit from mentors with experience in sludge audits.

- Use a tool to methodically collect, organise and analyse data from the sludge audit. A tool enables to organise sludge audit results, guide auditors through the audit, display results and prioritse frictions. Recommended features of a tool include guidance through a method, management of data, calculation of burden metrics, summary of results, suggestions for interventions and measurement of impact.

- Accommodate for behavioural journeys that are non-linear and diverse. Mapping non-linear journeys ensures auditors consider diverse people and paths to engaging with a process or service. This enables teams to account for people progressing through a service or process in different ways.

- Deploy an equity lens throughout the sludge audit process. Using an equity lens throughout the sludge audit enables auditors to address the disproportionate impact of sludge on underserved communities. Teams can use equity checklists as they complete the audit or identify an equity framework that suits the given context.

- Leverage feedback to challenge assumptions on sludge. The integration of feedback before, during and after a sludge audit is essential to selecting a process or service to audit, understanding people’s experiences and assessing the success of a sludge audit. Integrating feedback is important throughout the sludge audit by conducting interviews, onsite visits and surveys.

- Act to reduce sludge and evaluate progress. Sludge audit results should be used to develop solutions that address frictions. Teams should consider potential positive impacts, equity impacts and the institutional context when designing solutions.

- Build system-wide enablers to develop a sludge prevention programme. The systematic adoption of sludge auditing can be enabled by establishing clear and meaningful commitments to user-centred government services, considering institutional arrangements, embedding whole of government service user voice and data and promoting public sector capability.

The International Sludge Academy proved the applicability of sludge audits beyond Australia. By building upon and enhancing traditional approaches, sludge audits mark a significant milestone in advancing government efforts to make services and processes more accessible and fairer. The OECD Behavioural Insights team is eager to see these audits expand into new areas and to continue to work with governments to promote its widespread adoption.

The OECD and NSW are currently developing the next version of the International Sludge Academy, which will be accepting applications from a wide variety of teams working on service improvements in government. If you are interested in the International Sludge Academy 2.0, please get in touch at [email protected] for more information.

The good practice principles were co-developed with the New South Wales Government and members of the OECD Network of Behavioural Insights Experts in Government. They support governments in furthering the mission of enhancing public services and maintaining trust.

View recording

Fixing Frictions: ‘Sludge audits’ around the world

How governments are using behavioural science to reduce psychological burdens in public services

Published: 3 July 2024