Good News: Systems Change in the Public Sector is Possible!

The draft report “Working with Change: Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges” is now available online. In addition to the framework that was introduced previously on Hackpad, the team working on systems thinking at the Observatory has added four in-depth case studies from Canada, Finland, Iceland and the Netherlands to the analysis. The empirical cases show that systems change in the public sector is possible; moreover, that it can work in diverse settings: child protection in the Netherlands, responding to domestic violence in Iceland, engaging with the sharing economy in Canada, and in experimental policy design in Finland. The final version of the report is expected in June 2017.

Download the draft report here

The case studies proved to be very insightful about what is important for systems change in the public sector. They show that it is possible to move away from abstract discussions about complexity to hands-on practises in government. We have learned a great deal from the different case studies. Here is a snapshot:

In the case of Iceland, government designed an integrated support system – involving the police, social services, child protection and now also healthcare workers – to address domestic violence. The systems change started from the understanding that domestic violence is a social – and not a private – harm that affects everyone. This is known as the Austrian model of intervention in the case of domestic violence. The program started with an early pilot in the southern region of Iceland, in Suðurnes. Stemming from research findings on domestic violence, the community of Suðurnes came together to discuss how the problem could be addressed. As a result, different groups that previously were not used to work together (e.g., social services, police and prosecutors) came together to tackle the issue upfront. Enabled by new legislation – the program sets out a radical system change – from one organized around providers and authorities (mainly police) to one organized around the victim and focused on stabilizing the family. Part of the systems change was to start monitoring and evaluating domestic violence cases systematically. Changing very hierarchical systems – police, prosecution etc. – was far from easy, especially as no additional funds were given to implement the change, but today the different actors are working in a coordinated fashion to detect and respond effectively to domestic violence across Iceland.

In a similar field in the Netherlands, Jeugdbescherming Regio Amsterdam (in English: Child and Youth Protection Services in the Amsterdam area (CYPSA)) redefined its purpose and working methods through the “Vanguard method”, a system thinking approach based on the cycle of “check-plan-do.” The organisation was at the brink of financial collapse in 2008 and during this crisis the leadership saw the opportunity to take some time to analyse and redefine the mission of the organisation. As a result, the organization adopted a new mission for all its activities – “Every Child Safe, Forever” – and redesigned the whole system to fulfil that purpose and create meaningful impact. It was understood that only through changing complex family dynamics children’s safety could be guaranteed. Thus, a new way with working with families – “everybody present in a room” –, had to be adopted. To enable this change, a group of insurgent, change-minded employees were trained within the system method. Team by team, they took the whole organisation through the change process: everybody was allowed to experience the crisis themselves, not just be told about it. However, working in a new manner is not easy: many who did not get used to the new methods of working left the organisation in subsequent years. Having the right people to support the change and carry it through the implementation process is key for systems change in the long run.

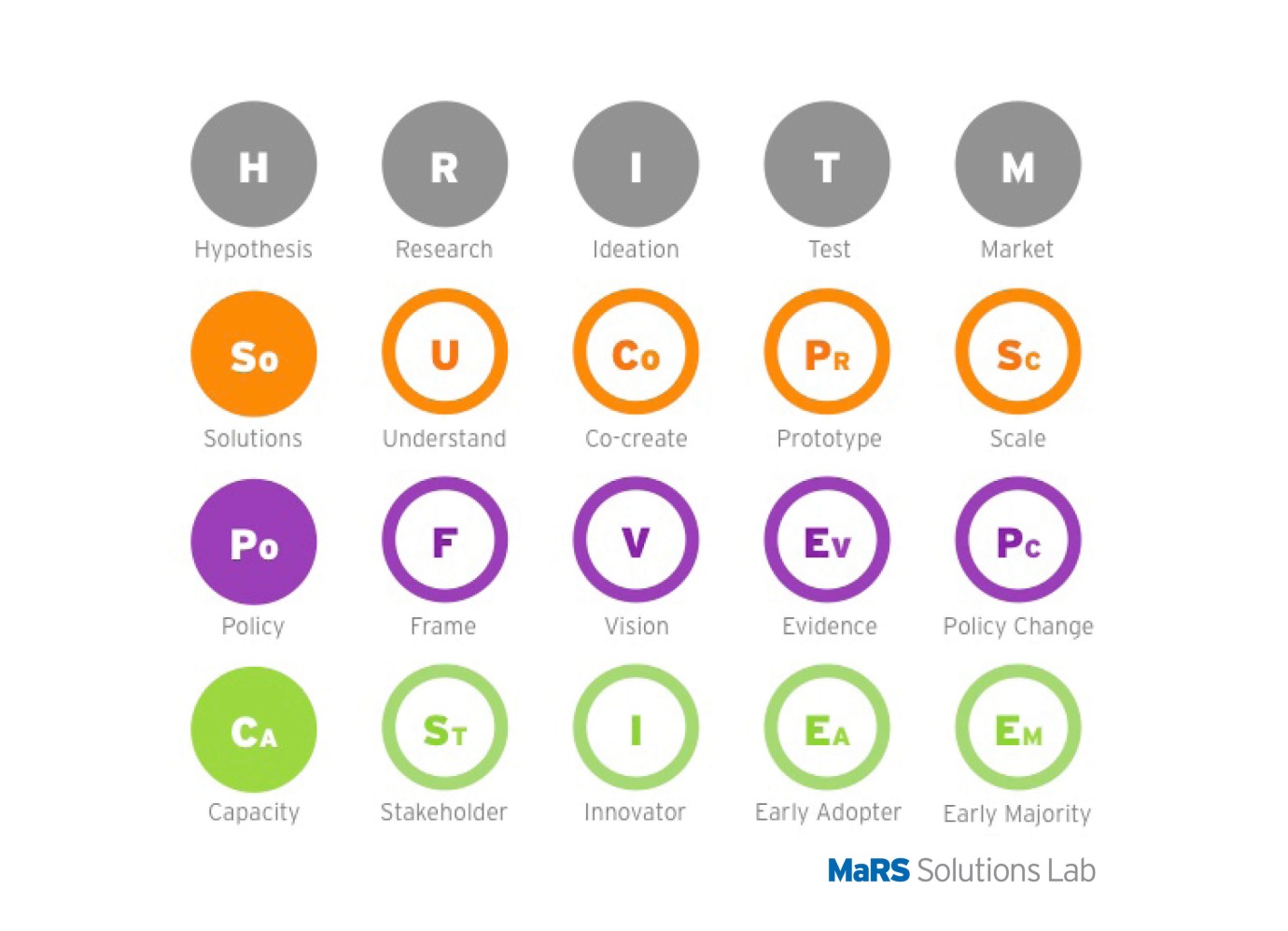

In Canada, the City of Toronto was confronted with a drastic change in technology – the rise of the sharing/platform economy. When Uber starting to operate in Toronto in 2014 without specific regulatory oversite, the city had to move quickly to regulate an unusual company and appease an alarmed incumbent industry. However, it became quickly clear that all levels of government – city, province, federal – had to be involved to make the change meaningful. Different types of policies connected to the emerging fields of sharing economy (housing and transportation bylaws, insurance, taxation, etc.) were regulated at different levels of government. This creates a problem: who has ownership over the issue? Much through coincidence – stars aligning – MaRS Solutions Lab became an independent arbiter who facilitated a productive dialogue between different stakeholders. Utilizing systems thinking and design methodologies, they proposed a user-centric vision and sharing economy city strategy for Toronto (and by extension for cities across Ontario) and contributed to a new form of legislation that enables the city and its citizens to both regulate and benefit from new entrants disrupting old businesses. Working across the board with the city, province, federal government, taxi industry and sharing-economy companies, they defined together what the public value connected to the bursting platform economy was and what a level playing field would look like for all. The case highlights the need to create a common language among all stakeholders to make changes on different levels of government symbiotic, especially, when confronted with radical change.

The case of Finland is slightly different as it tackles the ways of working of government itself. In 2015, Finland started to develop a new framework for experimental policy design. Together with Demos Helsinki, a Nordic ThinkThank, the Prime Minister’s Office of Finland employed a combined systems and design thinking approach to develop a new policy framework to carry out experiments in government. In parallel, key figures of the ruling Centre Party were involved with developing and spreading the idea of “experimental culture” in the Parliament of Finland. As a result, experimentation was included into the strategic Government Programme in May 2015 and an experimental policy design programme was set up. The new approach to policy design allowed both broader “strategic experiments” (formalized policy trials) – for example, the ongoing basic income experiment – and grassroots experiments designed to build up the “experimental culture.” Experiments are a good way to deal with uncertainty, test out new ideas before scaling them up. Thus, experimentation can be a big part in preparing systems change in government: the success or failure of a specific experiment will give insight about which direction to pursue next. The Finnish case in general shows that in many cases systems change has to accompany a change in the working culture itself. This does not happen by itself and time is needed for people’s perceptions to change. The conventional wisdom is that cultural change takes years, but this does not mean that radical transformations should be done far in the future. The Finnish case and the other systems change examples above, show that it is the decisive, thought-through and purposeful change (that might be difficult to stomach in the beginning) that brings forth broader cultural shifts in the future.

Studying the empirical cases of systems change was the most enlightening and insightful part of our understanding of systems change atOPSI. You can have a more detailed account of the cases outlined above in the draft report. Here are some of our main findings:

- While system transformation evolves differently depending on time and contextual factors, it is often triggered by the “perception” of a crisis, urgency for change. Systems change takes time and resources, so, not all public challenges are appropriate for systems thinking.

- After internalizing “crises,” organizations need to create room for dwelling – investing the time to understand and articulate both the problem and the objectives. Understanding the purpose of systems and framing problems accordingly is the cornerstone to analysing if existing systems actually produce the outcomes people are looking for.

- It is important to involve diverse stakeholders as early as possible to the process and take them through the same learning journey. Otherwise, it is difficult to explain to de facto outsiders why a new approach is needed. This makes time an essential resource in systems change, because people need to live through and experience the change rather than be told about it by a third party.

- Usually only high level leaders within organizations are able to create the space needed to explore unknowns on the system level and ease the way for radical shifts. This does not mean that senior management has to be in all the steps of the change process, rather they need to make their support explicit.

- Do not be afraid to ask help! Systems thinking requires different types of skills and capacities, and sometimes coming from a legacy sector can distort our vision. Having an outsider for an objective perspective, without the prior policymaking baggage, can be a good way to frame problems and take away stakeholders’ fears. Innovation labs and experts inside and outside the public sector can help with that.

We look forward to hear what you think, email us your comments and suggestions. OPSI will work on systems change and problem framing on the city level next and we look forward to working together directly with governments on their public challenges.

If you would like to be kept informed about this or our other projects on public sector innovation, you can sign up to our mailing list, follow us on Twitter, or join our LinkedIn group.