Systemic Governing – Applied systems thinking in practice

Guest blog from the Applied Systems Thinking in Practice Group, School of Engineering & Innovation, The Open University (UK)

Systems thinking in times of complex challenges

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown what governments can do when faced with an existential threat:

The climate and associated emergencies are existential threats. These will require even more of governments and of governance. Further, these new ways of governing are what is needed to enable governments to achieve real and lasting beneficial change, consistently, across the board. Our thesis is that it is only through new systems of governance and new ways of thinking and acting can the human world manage the climate and associated emergencies, reduce inequality and reestablish widespread confidence in government. This is termed ‘second order change’. A young Algerian woman interviewed recently by the BBC said:

‘I have decided not to leave the country. The system has to leave.’

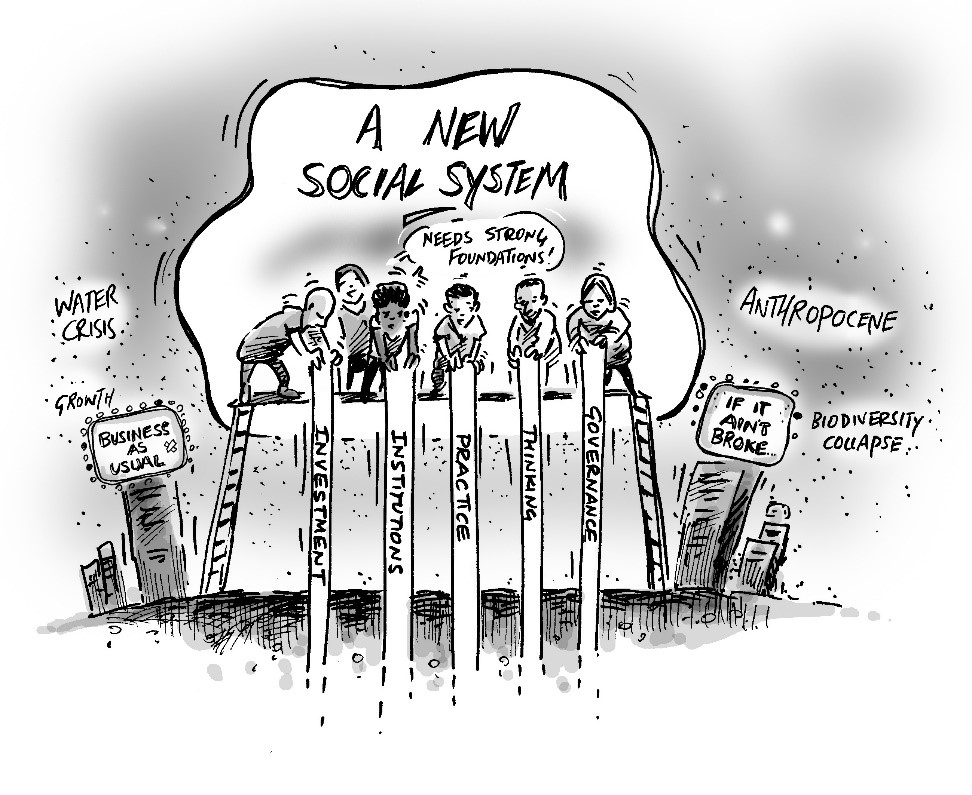

Our book is an invitation to us all to think about, and change, what we do when we do what we do. Leaders, administrators and practitioners, if imbued with systemic sensibility, systems literacy and – most importantly – Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP) capability, can engage in and lead transformative action. The potential is before us of a wave of innovation, particularly in systemic governing, in a period new to human history, an unfolding Anthropocene – the geological age in which humans have become a force of nature changing whole earth dynamics.

‘If we always do what we’ve always done, we’ll always get what we’ve always got’.

From the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Henry Ford’s maxim seems destined to continue unless a concerted effort is made to change our governance systems. The evidence for change is compelling. Such is the current volume and depth of critique from inside and outside government, few would cling to the notion that our systems of governing are working. Despite mostly good intentions, they struggle to produce results. Politicians and officials are as much victims of these systems as are citizens. Political and technological lock-in to institutions, policies, interests and lobby groups is a common governance failing. Ramshackle political processes are no match for the coming challenges.

Structure determined systems

Just as cats are structured through their evolution to kill birds – whether we like that or not – so many governance systems are structured to be incapable of responding to complex, uncertain situations. ‘Wicked’ situations transcend the period of elected governments, the attention spans of career politicians or the concerns of a fickle media. Constitutions, institutions and the rules we humans have invented ranging from voting systems to the separation of powers, are the structural ingredients of a governance system. These are part of the human social system. Almost all were invented before we realised we were in the midst of an unfolding Anthropocene –and are consequently and obviously out of date. Neither were they designed for globalisation, the rise of multinationals bigger than 70% of nation states, burgeoning social inequality, the internet and all that has followed, the distortions of the news media, ever-expanding responsibilities of governments, and a human-created technosphere – all that stuff from houses to rubbish and computers.

What is governance or governing?

Governance is different to government. Governance is what governments, boards, project teams do. It involves steering (think of a sailing boat) in relation to social purpose and, importantly, responding to feedback – thus learning and adapting, something few governments do consistently. No constitution in the world requires built-in, independent, timely, response-generating feedback. In the severe bushfires a few months ago, the Australian government was immune to feedback offered from the biophysical world about how dry it actually was. The severity of the fire season was knowable in advance. So, too, was the current pandemic. Despite the presence of plans and scenarios for pandemics, few governments were able to quickly activate what had been envisaged as being needed.

What is a governance system such that it can be said to be deficient?

In simple terms it can be seen as a generalised ‘diamond’ comprising the state (made up of the executive, parliament/congress/assembly, public service, staffers etc), the law, the private sector and the media, and civil society: a system of five key elements and the relations between them. Understood this way it soon becomes apparent that each element has major deficiencies, and the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

How do they malfunction?

One of the most powerful systemic obstacles in most governance systems is preferential lobbying (PL). In the prevailing economic system, business and government are locked into this once occasional but now ubiquitous practice. Studies show very high returns on investment for PL. It is wealth appropriating, not wealth creating. It maintains planetary destruction, strangles democracy and is at the heart of mass inequality. In some countries, it takes the form of state capture. If not convinced, take a look at how preferential lobbying by Big Oil, or Big Coal, or Big Tobacco or Big Pharma has driven decisions of governments. No one designed PL in, but it can and should be designed out.

What is missing from our governance systems?

Seeing governance in systemic terms makes what might otherwise seem impossibly complicated understandable, able to be acted upon to change. We propose adding to the old ‘diamond’ three new elements – the biosphere, technosphere and social purpose – creating new relationships and a very different systemic dynamic.

Collectively we humans fell into a trap when we began to think of the environment as a thing – something outside ourselves, able to be exploited, manipulated or regarded by conventional economics as an ‘externality’. We all carry the environment, that which surrounds, to give credit to its etymology, as part of us – the air we breathe, the water we are made from. As the pandemic makes clear, the biosphere will always do what it is capable of doing – we overvalue our agency at our peril. The Earth will survive us – but will the conditions for viable human existence? In a planet so much at risk, doing anything other than placing the biosphere at the centre of our governance model would be, arguably, the worst decision in human history.

Elements of the technosphere stare us in the face every day. But our regulations are designed to act only after some new technology’s insertion into our social fabric. Future governance should appreciate how technology functions in relation to who and what we are, and how it should operate.

Choices being made as we write about saving lives, whose life, a compassionate humanity, or saving the ‘normal’ economy exemplifies what we mean by our third new element, social purpose. Our argument is that the state or a political party or a fictitious market, are not able to deliberate on matters of social purpose. We should create new institutions of social purpose such as ‘constitutional assemblies’ or ‘climate emergency public commissions’ or other novel citizens’ engagements such as that proposed recently by former UK Chief Scientist, Sir David King to provide transparent, depoliticised, independent and expert knowing and advice – with all its caveats and uncertainties – for governing the pandemic.

Systems thinkers to the rescue

Into these structure determined systems has come a growing band of systems thinkers, and a growing catalogue of working examples of applied systems thinking in practice. The OECD’s OPSI makes particular conclusions for generating effective governance performances. Success has citizen engagement at its core: ‘Innovative governments are enhancing citizen engagement and ensuring public involvement at every stage of the policy cycle: from shaping ideas to designing, delivering and monitoring services. The goal is not only to improve the type and quality of services that governments provide, but also to transform the culture of government so that citizens are seen as partners who can shape and inform policy and services.’ Through this work the OECD is arguing for a new set of relationships between the state and, mainly, civil society.

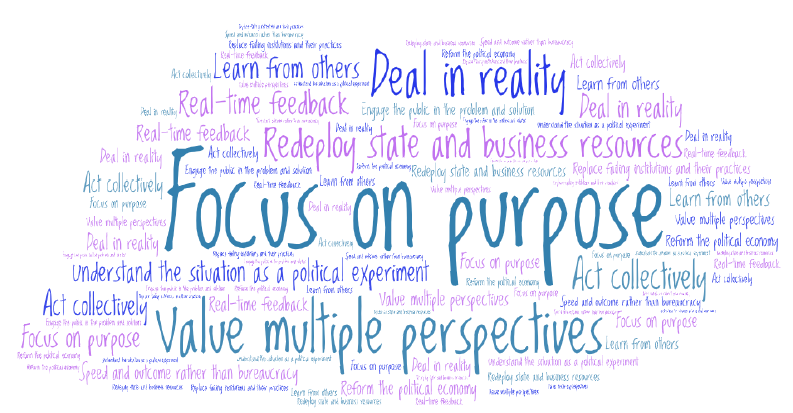

Several promising innovation pathways have emerged from OPSI work. These include governments:

- renegotiating what it means to be an ‘expert’

- arming public employees and citizens with tools to connect and establish dialogue

- building evaluation into the innovation process

- taking feedback into account

- not accepting the system as a given

- investing in human capacity

First or second order change?

What happens when government administrators, trained in the above processes, leave knowing that the structure determined system they work in will prevent system change happening, condemned to valiant efforts that ultimately make a difference only at the margin. They will be free only to improve within the existing system – first order change. Will systems thinking or preferential lobbying prevail? For as long as PL remains, what chance has STiP got of becoming the new normal? Will enlightenment dawn or will the established structures continue to do what they always did?

What would second order change look like?

Governance systems can be designed so that preferential lobbying is eliminated, for example. Based on our research, we propose these nine clauses to be enshrined in tamper-proof constitutions:

- Establish fair and limited political party funding

- Ensure powers are separate (i.e. no politicized judiciary)

- Remove political patronage

- Use effective proportional representation for all elections

- Introduce participatory and deliberative forms of decision taking and acting

- Change how government decisions are taken – STiP it, don’t politic it

- Invent institutions and practice that vet these decisions/designs for action

- Vet the results of these decisions to learn from their consequences and to establish accountability for them, principally through cybernetic feedback and a fourth separation of powers

- Eliminate widespread bribery.

Enacting a governance system?

In our book we provide 26 principles for systemic governing to produce and enact a new model of governance. Prior to the pandemic, this may have looked like an arduous ambition. Now, Covid-19 has made manifest that the systems we have are but the systems we have, all are human inventions and all can be reinvented. The rulebook has been ripped up. Like the virus, the biosphere cannot be politically ‘spun’ out of existence with rhetorically massaged statistics and deft hand-offs.

OECD data shows trust in most governments has been in decline for years. To change this trajectory and the systemic unfolding of the pandemic is a compelling task in the face of the exigencies of the Anthropocene and a business-as-usual mentality. A change in trajectory does not just happen, though unplanned, emergent surprise does occur a lot. We can, however, act collectively to change it. And first we have to mount an intellectual revolution.

The aspiration of our book is to prompt change such that we can secure peace and live in harmony with the biosphere – and each other. Our enemies are the historical systems that are degrading it, and diminishing the lives of many people. The opportunity now for researchers in the OECD and everywhere is to build the intellectual case for second order change. How that can be done, we will pursue in a future blog.