Portfolio Exploration Workshop – Part II: Testing it in Sweden

This post is a follow-on from our Part I post, which provided an overview of the design and development of our Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop based on OPSI’s Innovation Facets model.

Earlier this month, we facilitated a workshop with those from the public sector innovation ecosystem in Sweden. We were hosted by Vinnova, Sweden’s Innovation Agency. Vinnova invests 287 million euros annually in research and innovation projects across public, private, and academic sectors, especially in early-stage, high-risk ideas in order to test their potential. It continuously monitors and evaluates these projects against its goals around sustainability and private sector competitiveness. Vinnova constantly assesses its portfolio of innovation investments as well as its innovation strategy, so this workshop fit well for their role as key actors in their innovation system.

The Swedish Government is highly devolved with much authority being delegated to regions and municipalities. Culturally, Swedes are consensus-based decision-makers, which for government means that sometimes the initial phases of initiatives are slow, but move very quickly once consensus is reached. Vinnova is also currently considering a mission-oriented approach (for example) to its work and trying to navigate how that will work in such a consensus-based society. Having consensus around a common language and understanding of purposes of innovation is also helpful in such a context. We adapted our Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop to suit the Swedish context, Vinnova’s jobs-to-be-done (see Part I blog), as well as Vinnova’s near-term interests.

Because the portfolio exploration workshop involved bringing people together from across the Swedish innovation ecosystem, we started with an activity that was partly an opportunity for introductions and partly a dive into the content. We asked, “What drives your activities?,” and participants physically moved into areas of the room based on their responses.

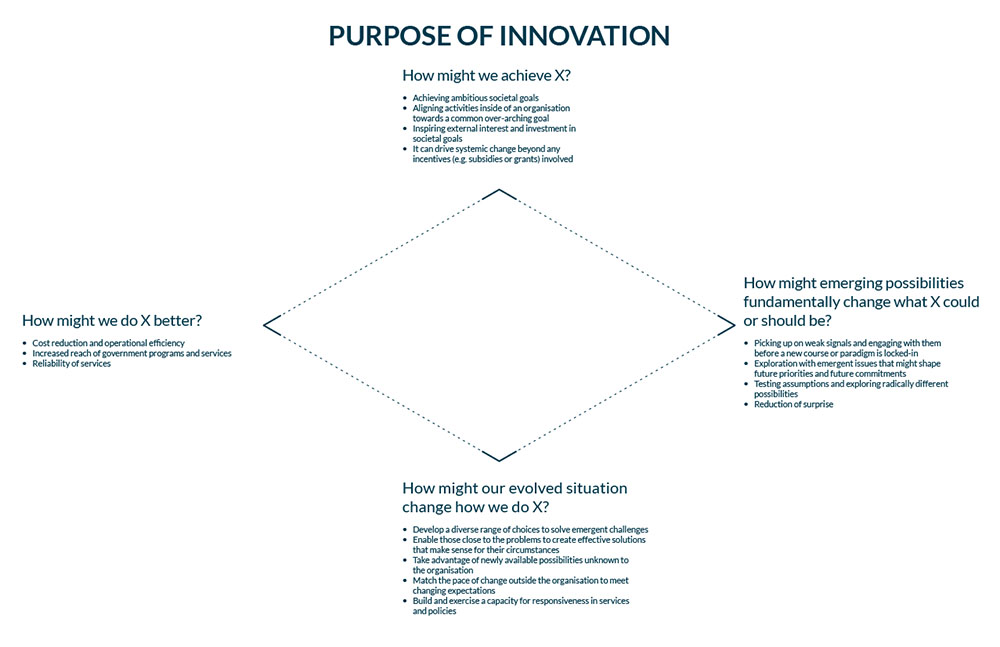

Next, we introduced participants to the concepts behind the innovation facets model without introducing the model language itself.

We asked participants to map example projects/activities to these key questions, which started prompting the lively “it depends” conversations.

Only after participants had built up an understanding of these key questions did we introduce the language of the innovation facets model. After introducing the model and its associated working methods, approaches and tensions, we asked participants to map a portfolio of innovation projects/activities borrowed from other governments.

Even when working with participants that have their own portfolio of projects and activities, we intentionally include this activity first so that participants focus on contextualising projects/activities to the model instead of getting into the details of their own work, which some may feel inclined to defend, advocate, or describe in depth. With certain groups of workshop participants, this can also prevent one person or group from dominating the conversation by discussing all of their projects/activities they are eager to highlight.

In Sweden, this activity also enabled us to have a discussion about the overall shape of the resulting portfolio of projects/activities without fear of judgment—it was someone else’s portfolio, so criticism and dissent were ritualised and normalised among the group.

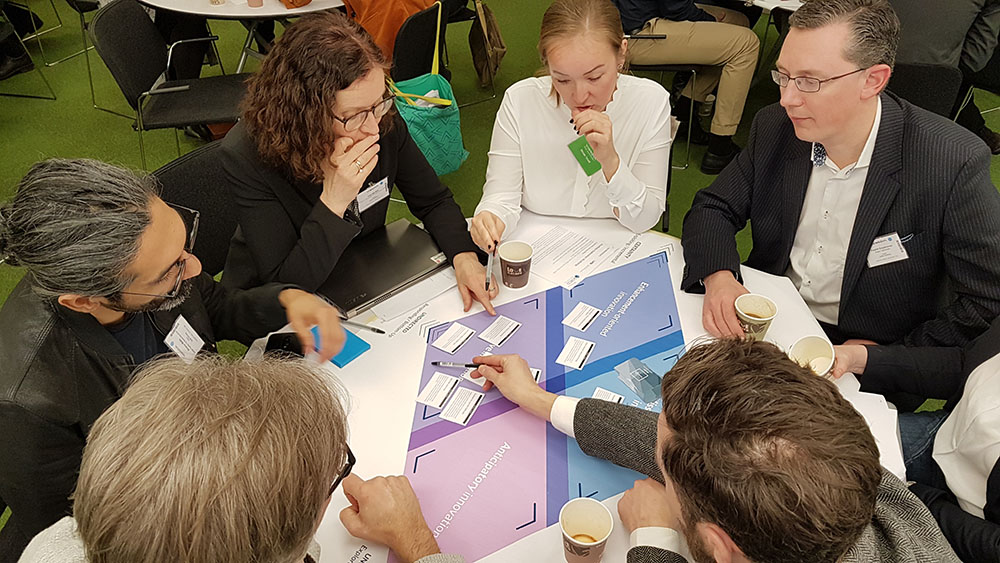

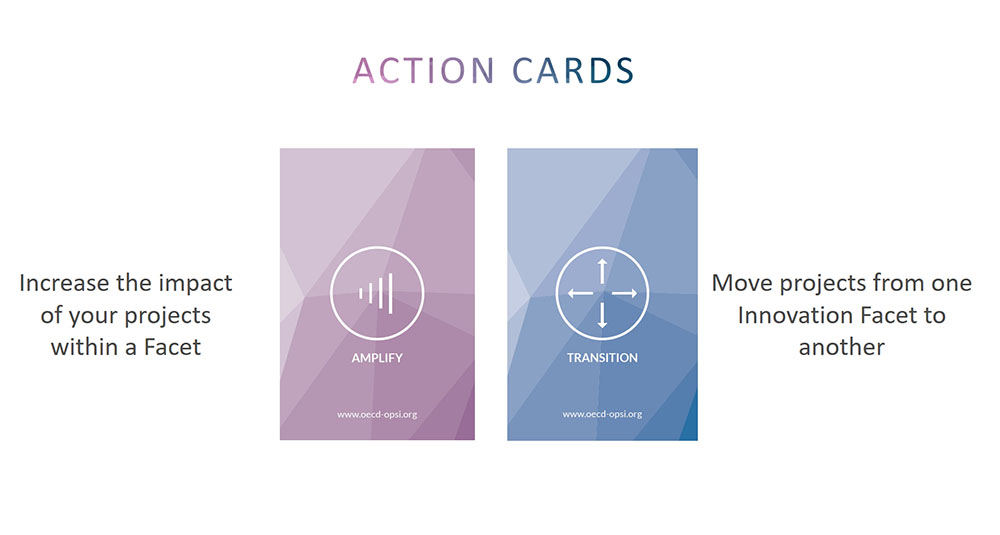

Then came the most “game-like” part of the workshop. We asked participants to combine, by the chance draw of a card, which action they would take to amplify, scale, or transition a project/activity in their example portfolios.

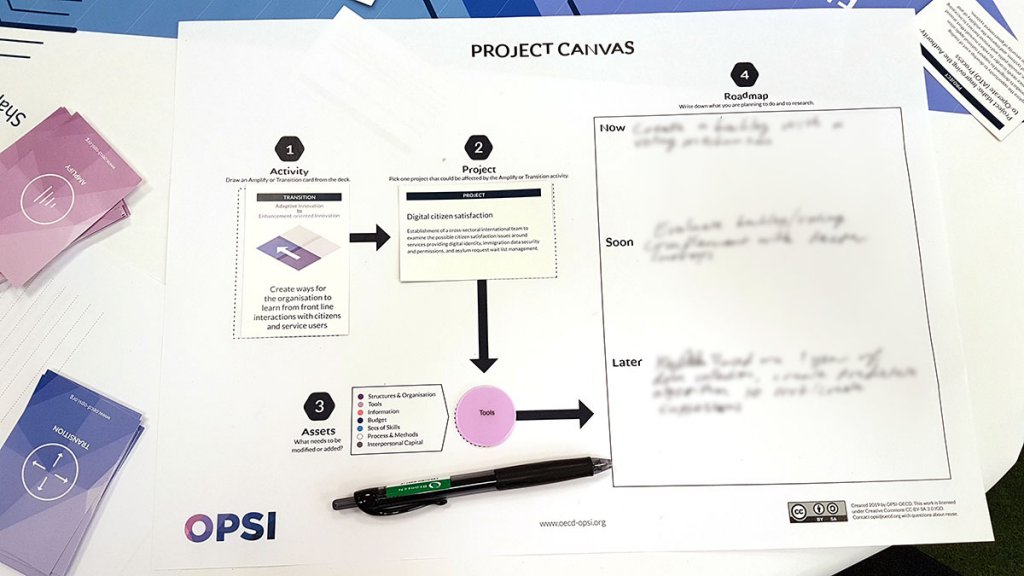

Each group was given a sort of game board that prompted them to combine a project/activity, an action, and a set of levers or assets they could modify within their organisations. The levers or assets were represented as plastic chips, which gave the activity a real game-like feel. Based on this combination of factors, participants were asked to identify near, mid, and long-term plans to set the changes in motion.

By radically recombining these items, participants built up the practice of transforming current projects/activities and built a deeper shared understanding between the projects and the organisational and system factors that produce them.

Only after we built up their practice and comfort with busting open and mangling others’ projects/activities did we introduce their own projects/activities, which participants had provided in advance.

Once participants built innovation portfolios using their own projects/activities we were able to get to the critical questions about Sweden’s innovation strategy. By starting with projects/activities instead of the policies and support structures purportedly driving innovation in Sweden, participants demonstrated for themselves what kind of portfolio their innovation system is currently producing. This ended up being an “ah-ha” moment.

Next, we stress-tested their portfolios by asking:

- What led to the current activity portfolio?

- Is someone stewarding this overall portfolio? Is that needed?

- Are there strategies and policies supporting each facet? What are they?

- Is the current balance indicative of a temporary or long-term trend?

- Is the balance of the portfolio supportive of our overall mandate or purpose?

Finally, we asked participants to use the action cards and asset chips from earlier in a proactive way, to build their own playbook of actions based on how they want to transform and build up their entire portfolios.

Lessons learnt in Sweden

We learned a lot from our experience running the portfolio exploration workshop in Sweden. These lessons include:

- This much content is difficult to fit into one day. The Swedes were able to keep up, but I think we exhausted everyone. Only so much new content should be introduced at once and pleasant experiences are more likely to be practised later. Therefore, we will revise the basic workshop recipe so that it is spread into two days of modules. We realise that getting two days of people’s time can be quite difficult, so we will adjust future workshops depending on the needs of the host and what is possible.

- We need to develop more support for defining what portfolios “should” be in addition to what they are before deciding on a playbook of actions. This is a strategy question that often involves multiple levels of analysis (individual, group, organisational, system) and implies a direction based on political or societal interests, which can be difficult to distill into a workshop format. This is something we will continue to develop in the medium and long term.

- We need more distinction in our workshop between innovation projects/activities, the projects/activities of innovation system stewards, and overall innovation support structures at the organisation and system level, such as policies and funding streams. We mixed all of these aspects together in the workshop to force participants to make these distinctions, but it ended up being too much complexity to digest in a one-day workshop. We will include this as well in our next iteration of the workshop recipe.

Run your own Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop

Development of the original workshop was supported by the Mohammed Bin Rashid Centre for Government Innovation. All of the materials described above, except for the Swedish projects/activities, are available on our website for download and reuse.

If you are interested in having us help you run this workshop or helping you adapt the basic recipe to your needs, please feel free to reach out.

If you have thoughts or feedback on the workshop overall, we would very much like to hear from you. Start the conversation by adding your comment below or email us.