Governments: Governing or Governed?

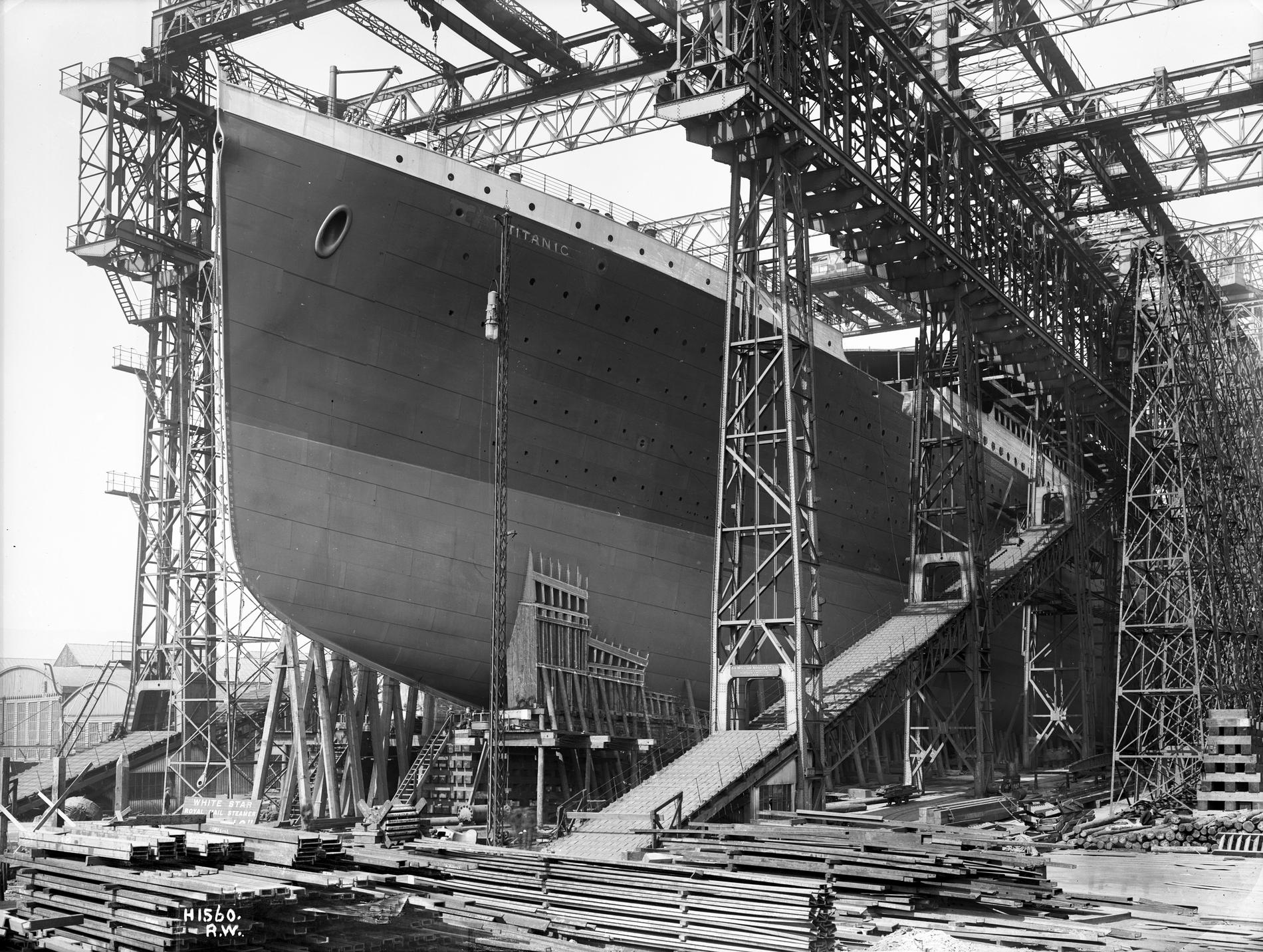

In April 1912, an icon set sail from Southampton, heading into the future and making history at the same time. The Titanic, “ship of dreams”, was the height of technological achievement. Retrospectively referred to as “unsinkable”, she might as well have been called “future-proof”, such was the confidence she commanded. We all know what happened. We also know the main lessons learned: lack of lifeboats, a chaotic evacuation, and doubts over whether a floating wooden panel could accommodate two people or just one.

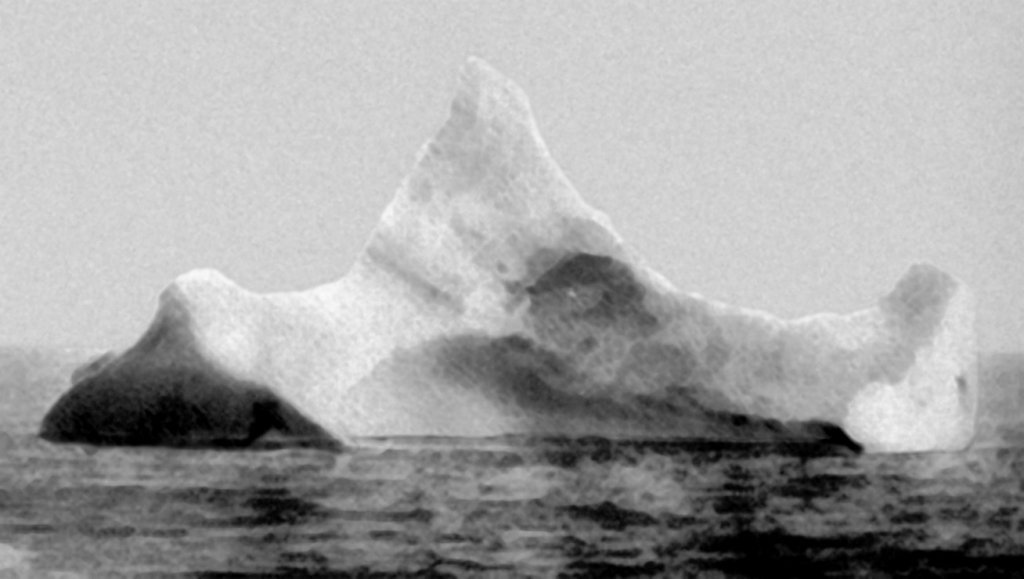

But all of these lessons have to do with the actual ship. The lesson we usually miss is this: humans could control the ocean liner, but not the ocean. The night of 14 April 1912 was moonless and pitch dark. The water around the Titanic was completely calm, now known to be a sign of nearby ice. There were no waves to indicate the presence of icebergs. A haze on the horizon further obscured the view ahead. By the time the iceberg was spotted, it was too late to respond as the ship was too large with too small a rudder. In other words, there were warning signs of danger, the conditions made it harder to spot hazards, and the response was too slow.

Policies are never unsinkable

Just like shipbuilders, governments aim to offer citizens the greatest well-being and quality of service money can buy. But just like mariners, they too will sink if they fail to observe, understand, and prepare for adverse conditions beyond their control. Just like seaworthiness, success for governments depends on a complex interplay between the organisation and its context. Government govern, and they are governed by the trends, shifts, and needs of the world around them: processes like digitalisation, climate change, and demographic shifts.

Moreover, in governments, the captain changes every few years, the vessel is usually difficult to steer, and the course ahead is littered with diversions, dangers, detours, and distractions. Governments must therefore learn to anticipate better and respond faster, while still navigating in the right direction. They need to explore the future of the public sector, and create the public sector of the future. How can they further develop these indispensable capacities?

In governments, the captain changes every few years, the vessel is usually difficult to steer, and the course ahead is littered with diversions, dangers, detours, and distractions.

On Friday 12 March, OECD OPSI organised a session on the future of the public sector as part of the international peer workshop on Anticipatory Innovation Governance hosted by the Government of Finland with the support of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Programme. Experts from governments, international organisations, and knowledge institutes contributed insights on the state of the art of how governments anticipate and respond in 2021. This blog article shares some of their key contributions.

Anticipating better: exploring the future of the public sector

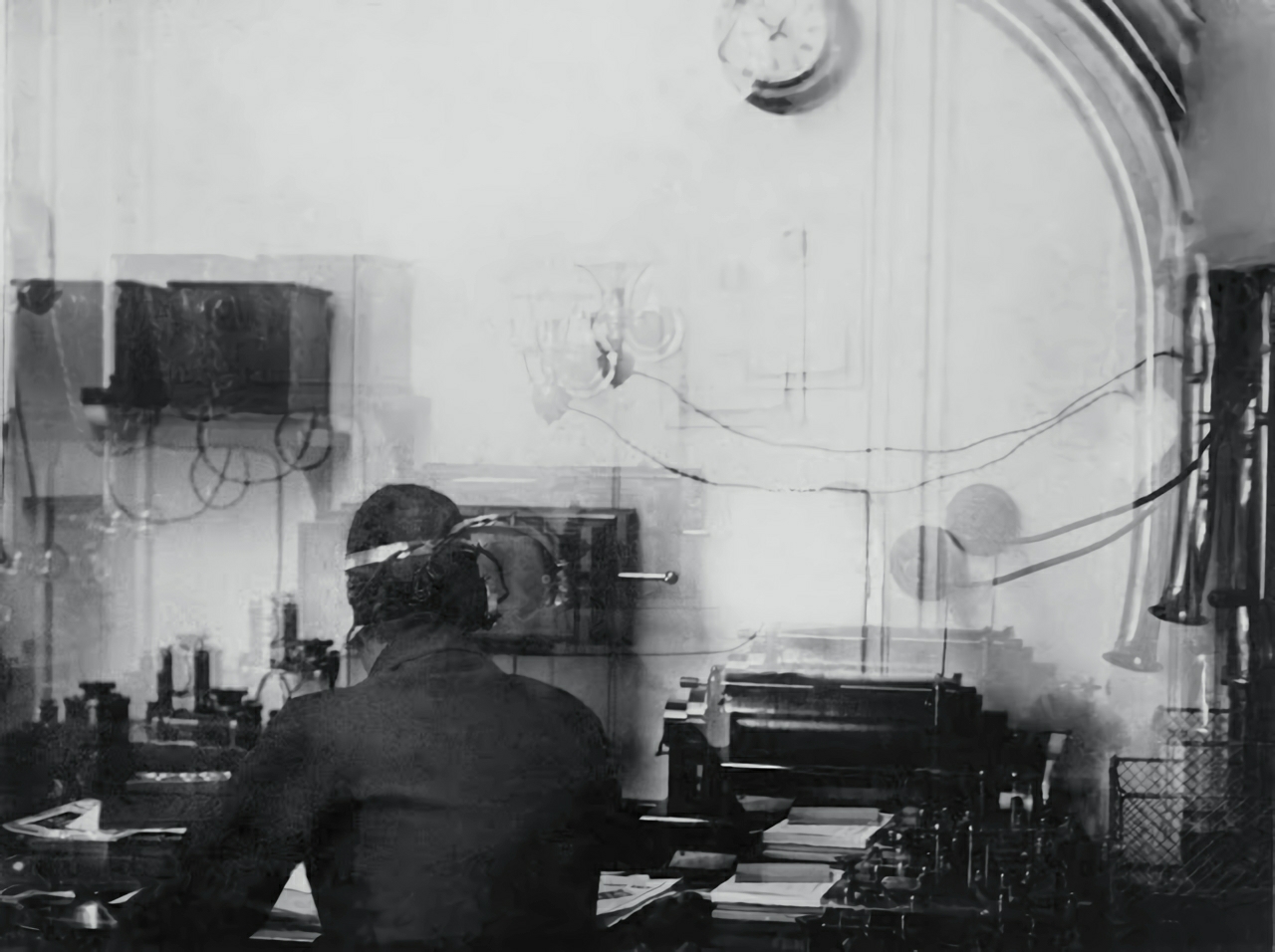

Governments today have numerous challenges both present and emerging. It can help to look at trends, but data are always of the past, and looking only in the rear-view mirror is not enough. In his opening remarks, Peter Pogačar, director general of the Slovenian Ministry of Public Administration, immediately drew attention to the need to look ahead: “in order to be ready to navigate the future as best we can, we need to understand where disruptions are happening and where the world is heading.” Pogačar pointed to cooperation and collaboration with outside actors, other governments, and citizens as one way to better identify and understand emerging change. He also noted the rising use and usefulness of data and analytics to enhance service delivery.

Liana Tang, Deputy Director at the Centre for Strategic Futures in Singapore, explained how to gain this understanding: through a process of “scout, challenge, grow”. Scouting means to be on the lookout for signs of emerging change (also often referred to as horizon scanning); challenging means having the capacity and structures to make sense of what is observed and what it could mean for the government—including long-established processes that need to change. Growing means making futures capabilities part of the functioning of government, including through training and staff rotation that promotes planning for the long game.

Also reflecting on uncharted and potentially treacherous waters ahead, Rainer Kattel of the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose at University College London referenced the classic futurist quote “the future isn’t what it used to be”. He further elaborated on the capabilities public sector organisations must develop to better read signals of change and learn from them. Among those were the ability to frame and reframe problems. For example, with climate change, it is an energy and environment problem, but it is also a food problem. Another capability is openness: all panellists talked about the idea of public organisations becoming more open by design, able to engage with different stakeholders and users. Furthermore, we need to build diversity into our organisations to see the future through multiple pairs of eyes and interpret it through multiple minds. This last idea was particularly welcomed by the audience, who expressed agreement on the online chat and added comments about the importance of incorporating the viewpoints of all age groups.

Responding faster: creating the public sector of the future

While navigating turbulent tides, governments will still be expected to provide excellent services, at least on par with the private sector, that are customer focused, efficient, innovative, and enabled by technology. This assertion from Pogačar highlights the other side of the challenge governments face: reforming their own organisations to ensure they continue to perform. He drew attention to the need for strategic workforce planning to ensure that civil servants have the skills they need to innovate and respond to the changing world.

Christian Bason of the Danish Design Centre noted that whilst certain trends like design thinking, systems approaches, and innovation labs have been valuable, the forces that keep public sector organisations in check as “fundamentally stability-seeking, bureaucratic institutions” have also been strong. Bason outlined four main dimensions of public sector reform: approaches, organisations, leadership, and thinking. He also introduced three principles for leading innovation by design, with their associated activities: exploring the problem space, co-creating new solutions, and making the future concrete.

Andrea Cooper of Connected Places Catapult used the analogy of a volcanic eruption to describe the momentous disruption of the covid pandemic: when rock turns to liquid there is a precious moment of previously solid structures becoming malleable. In responding to unprecedented circumstances, this is the moment to think about what policy levers governments have. Cooper’s work involves a ‘Government as a System’ tool to help policymakers think beyond the obvious tools of tax, regulation, lawmaking and so forth, and to also use tools such as convening and stewardship of systems. It is part of a broader, but difficult question of how to shift policy-making to a more open, collaborative endeavour. Thinking about government as a whole, Piret Tõnurist of the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation noted some of the different and potentially contrasting trends in public sector organisations:

- A more centralised control and algorithmic governance of services as well as data itself, with more top-heavy but simultaneously flatter hierarchies below a select few decision-makers.

- Hyper-personalised and distributed systems, as it is increasingly possible to identify individual needs and experiences, and then build up services with a bottom-up and local perspective.

A further insight from Cooper considered how can we go ‘with the change’ instead of trying to sail into the wind, given many processes are so large and hard to influence. One example is to learn from the changing perspectives of different generations. If we move with changing agendas and values, we can make the most of the moment. Another option is to build on the idea of a ‘trim tab’, the bit of a rudder in a ship that moves first to break water tension, to enable boats to move: in the policymaking context, how can actors influence the system through an accumulation of effective interventions?

Navigating in the right direction

Last but not least, a crucial consideration about purpose and values. Bason told organisations: know who you are and where you’re headed. For Cooper, the central question for designing policy for the future is what kind of world we want to live in. It is the central question for politicians but also for citizens. And, when we know what world we want to live in, we need to understand our current world in order to work out how to get to the future one we envisage.

Likewise, Tõnurist emphasised that institutions must be guided by a strong sense of justice and ethics. For example, the dividends of future transformations will not be distributed equally; as such, governments may need to plan for transformations that may impact particular groups like low-skilled workers.

Reflecting on the future of the public sector and the public sector of the future, it will not be enough to forge blindly ahead without surveying the changes emerging around us. It will also not be enough to simply observe change and not do anything about it. Only through strategic foresight and anticipatory innovation will governments be able to envisage and make the changes needed to navigate and adapt in these unprecedented circumstances. The OPSI programme on Anticipatory Innovation Governance explores how governments can put this into practice. Read more in our brief.