Innovation facets part 3: Enhancement-oriented innovation

In our first two pieces looking at the innovation facets, we have described how each facet has different characteristics, and how different types of change are associated with different types of innovation. In this post, we dive into the specifics of the enhancement-oriented innovation facet – what it is, what role it plays, how to support it, and the key considerations.

This post is us at OPSI “showing our work”, as this is still very much thinking that is evolving. Your feedback will help us in distilling the key messages, to ensure practical guidance for public servants everywhere.

“An increase or improvement in quality, value, or extent”[1]

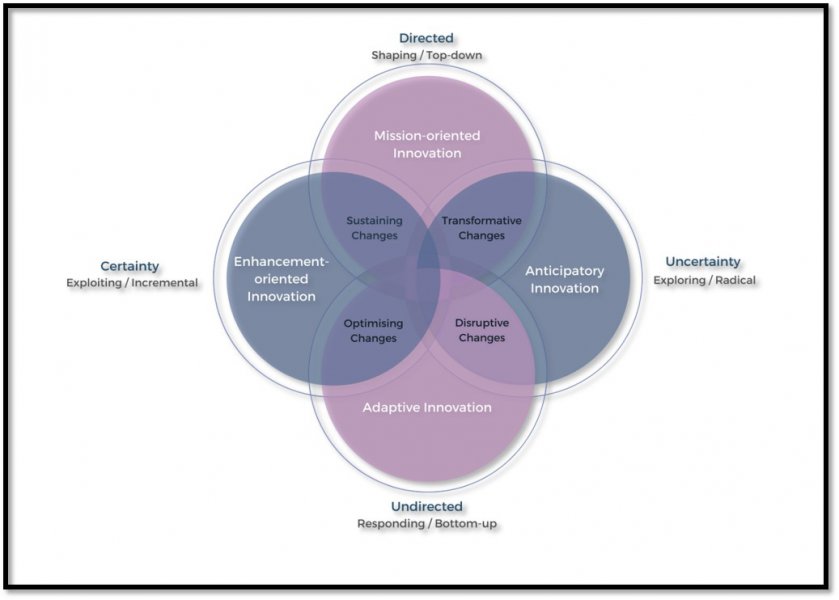

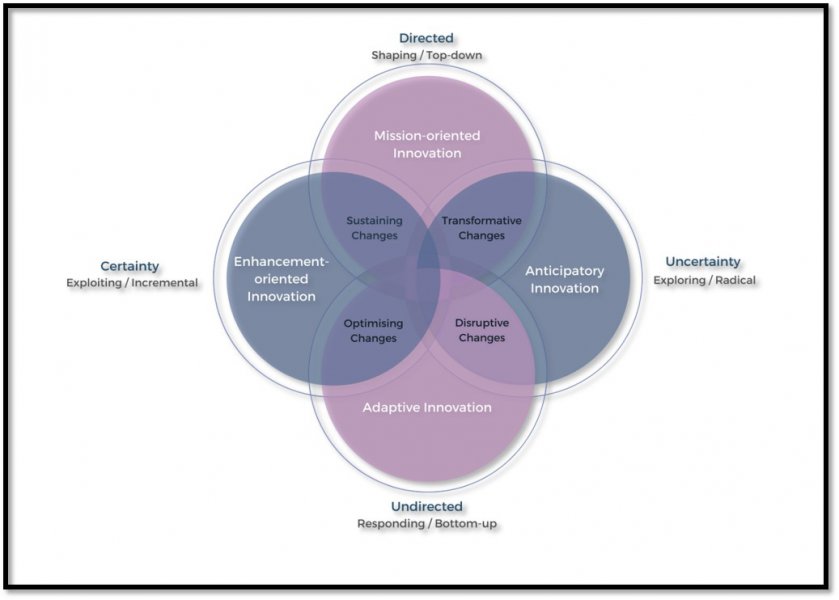

As we noted in the first post in the series, enhancement-oriented innovation:

- focuses on upgrading practices, achieving efficiencies and better results, and building on existing structures, rather than challenging the status quo

- will generally exploit existing knowledge and seeks to exploit previous innovations. Innovation such as this can achieve greater efficiency, effectiveness and impact from existing processes and programmes

- is illustrated by the use of behavioural insights to improve the response or compliance rates for matters such as on-time payments. Such innovation is not revolutionary or disruptive, and it does not involve rethinking the fundamentals of what’s being done, but it does involve a changed perspective and engaging with people in a different way

- is traditionally where most governments have focused their innovation efforts.

My colleague Piret Tõnurist gives a quick overview of enhancement-oriented innovation:

What does enhancement-oriented innovation involve?

Enhancement-oriented innovation often starts with the question of “How might we do X better?” It is not about questioning what is being done, but rather how it is done and whether it can be done differently, and hopefully better.

At a working level, it is about trying to learn more about how things work and trying to extend upon that. Common methods or practices that underpin enhancement-oriented innovation are generally structured learning processes to help consolidate insights and build upon them. Example practices include lean, business process management, quality control, and behavioural insights.

Enhancement-oriented innovation is the facet that can be hardest to distinguish from normal business process improvement. While there is no hard dividing line, the characteristic that can be seen with enhancement-oriented innovation but not with normal process improvement is some element of unpredictability. If there is nothing unpredictable about the process – i.e. if the degree of novelty is minor and there is a high degree of confidence about what will happen – then it is not innovation, as there is no application to a new context and therefore little new learning will occur. In many instances of enhancement-oriented innovation the level of unpredictability (or uncertainty) will still be pretty low, but there will still be some question as to whether it will work or unfold as intended.

Some example cases that we have seen that illustrate the range of enhancement-oriented innovation include:

- the use of tools to better match job seekers with opportunities that more closely fit their skills, experience and knowledge

- introducing smart parking technology to reduce traffic congestion

- providing intelligent street lighting to improve lighting quality, efficiency, data collection and safety

- the use of big data to improve HR functions and reduce costs, such as with public procurement

- using design thinking to encourage the take-up of online services

- a structured approach to behavioural change to reduce the misuse and waste of blood products in hospitals.

As can be seen, enhancement-oriented innovation can cut across all domains of government activity, vary in scope, and can be about reducing costs, increasing the reach of government programs, improving operations, or helping to save lives. The common elements are that they are more augmentations to what is, rather than really rethinking what could be (though that can sometimes follow).

What to watch out for with enhancement-oriented innovation?

Enhancement-oriented innovation is the most straightforward of the facets, in that it is the one least in tension with how things are currently done, and therefore the one where innovative activity will be resisted least. That said, there are some potential issues that are particular to this facet:

- Diffusion of what works. Good ideas and practices from enhancement-oriented innovation happen in response to specific contexts, and therefore may not be broadcast or diffused to other areas, even though they could have relevance elsewhere. Good things can happen in pockets that lack visibility to others.

- Over-specialisation. If there is considerable enhancement-oriented innovation occurring, then it will be likely that different areas of the same organisation may get increasingly specialised and start to differentiate in their core practices and processes. This can lead to excessive divergences within the organisation, jeopardising shared ways of working and functioning.

- Over-investment. Augmenting what is can sometimes mean that the status quo is improved just enough that something keeps on working, when actually it might have been a sign to rethink or revisit how things are done. Sometimes enhancement just allows a practice that is no longer appropriate to continue to be done, but faster/more efficiently (e.g. being able to do more service transactions rather than looking at whether the service process could be simplified).

- Missing the trend. A focus on enhancing existing activity can sometimes leave an organisation or a particular service/practice blind to larger shifts and changes in the environment (e.g. being able to develop photos faster did not help for when photos became digitised).

How does enhancement-oriented innovation fit within a portfolio?

To be effective over the longer term, any organisation or system will require a portfolio approach in its investments and efforts. In an uncertain world, you cannot predict the type, scope or direction of change that you will be confronted with. Therefore governments need to invest in multiple strategies if they are to both avoid being blind-sided, and so that they have a range of choices available to them in how to respond.

So how does enhancement-oriented innovation fit within a portfolio approach?

Enhancement-oriented innovation is about getting the most out of existing investments. Out of all of the facets of innovation, enhancement-oriented is the one with the clearest pay-off, and with the lowest apparent risk. It is the least challenging to existing operations, as it enhances rather than replacing or questioning them. These characteristics mean that enhancement-oriented innovation is the strategy most often used by governments, and the one that standard operating practices are least challenged by.

We suggest that enhancement-oriented innovation will always be a big and valuable part of any effective public sector’s innovation portfolio but it cannot, and should not, be the only part. A portfolio that is overly weighted on this facet will lead to being caught unprepared for bigger shifts in expectations. Over-reliance will hinder the ability to deliver on more ambitious agendas, and lead to over-investment in approaches that may no longer be suited to the context.

What are the likely preconditions needed for enhancement-oriented innovation?

In order for enhancement-oriented innovation to occur several factors are necessary:

- A relatively certain operating environment. If there is considerable disruption and fire-fighting then it is likely going to be difficult to get the necessary attention or support to engage with enhancing the status-quo. In some cases, embarrassing public failures can seed the need for enhancement or other types of innovation, but political will and capital is often needed and quickly expended.

- Consistency in key people and relationships. If there is high turnover, it may be hard to get buy-in for adjusting current operations.

- Structured learning. If there is poor knowledge management, then the learning required to inform the enhancing-type innovations will be patchy.

- A clear sense of intent or defined activity. Where there is no real clear sense of what is either trying to be achieved, or no real sense of the parameters of the activity, then it will be hard for employees and others to understand why or what to enhance. For instance, a government policy will be difficult to enhance through innovation if it does not have a clear sense of the stakeholders, the issues that are in scope, or the objectives.

How can enhancement-oriented innovation be supported?

What will not only allow enhancement-oriented innovation to happen, but will actively help it? We suggest that there are a number of things that are particularly relevant to supporting the facet of enhancement-oriented innovation:

- Clear functional accountabilities (i.e. who is responsible for the relevant activity)

- Effective baseline information (i.e. some degree of understanding about the current performance)

- Formal feedback loops that provide intelligence about how things are working (or not)

- Engaged or incentivised employees, who have opportunity and motivation to suggest and/or implement innovative ways of enhancing things

- A degree of commitment to, and support for, the existing activity, but some openness to new ideas or changes in how things could be done

- A risk-averse or risk-conscious environment, i.e. there is an ever-present awareness of the costs of doing something more radically different and therefore greater room for smaller changes.

How to sustain enhancement-oriented innovation in the long-term?

To sustain enhancement-oriented innovation as a practice/portfolio component, it is valuable to consider:

- Creating space for public servants to feel empowered to take small risks that improve the efficiency and effectiveness of things they are responsible for

- Supporting organisation-wide performance data collection and communicating about data trends as part of formal activity review and planning activities (i.e. dashboards, performance reports, etc.)

- Looking for best practices within organisations and systems so as to imbue a culture of ongoing enhancement and learning about how to drive more effective and efficient behaviours.

Enhancement-oriented innovation is likely to be the easiest to sustain from a portfolio perspective given that it is the least challenging to the status quo, and thus requires the least adjustment generally. It will also often provide the clearest and quickest pay-off in terms of value-add.

What can derail enhancement-oriented innovation?

Each facet is vulnerable to being jeopardised in different ways. For instance, enhancement-oriented innovation can be disrupted or derailed by:

- Moving key people out of the area, so that learning is disrupted or lost

- Continually adjusting or changing the function or its parameters, so that any learning cannot be applied

- Putting emphasis on process concerns, so that there is investment or attachment to how things are done, rather than whether it is done in the best way

- Requiring high-level approval or authority for any changes, so that the transaction costs involved in putting forward or testing new ideas are higher than the potential benefits.

Any or all of these sorts of interventions can create an environment or circumstances where enhancement-oriented innovation will be reduced or limited.

What are the signs that the innovation activity is transitioning to another facet?

In our innovation facets model, we note that innovation activity can, over time, move from one to another. Some signs that enhancement-oriented innovation activity is transitioning to the other facets include:

- Towards mission-oriented innovation: The focus on the task at hand (e.g. a specific service and how it is performing) starts to shift towards the underlying goal or aim. The attention moves from the process (how are we doing this) to the outcome (what are we trying to achieve). At an individual project level, this may occur when a project reveals significant benefits that could be scaled across a much wider range of activities. At a portfolio level, this might be when a project transformation (e.g. digitisation of a service) leads to insights that would be applicable at a whole-of-sector level (e.g. digitising all of government).

- Towards adaptive innovation: The focus moves from the how of what is being done, to the experience of what is being done. Rather than a focus on perfecting the activity at hand, the attention shifts to understanding how the activity actually interacts with the real world, and whether or how it is working. At an individual project level, this can be seen when a focus on process starts to blur with a focus on the client (i.e. co-design helps to reveal benefits not just for the organisation but for better meeting the needs of those being served). At a portfolio level, this might be when sector-level enhancements reveal insights into deeper needs (i.e. when digitisation results in dashboards that give much faster feedback about performance, and thus what citizen expectations actually are and how government services are really working).

- Towards anticipatory innovation: There is a shift from accepting the status quo (“we do this, and therefore this is what we do”) to questioning not just whether it is the right way of doing things, but whether it is even the right thing to do. At a project level, this might be prompted by a situation where the introduction of an enhancement (e.g. a more efficient payment system) reveals fundamental mis-understandings about what is actually needed or possible. At a portfolio level, this might be about a situation where a new technology or business process (e.g. the sharing economy) results in new issues that make existing optimisation (e.g. enhancing the system around taxicabs) entirely redundant.

An ongoing dialogue

In the next posts we will take a similar look at each of the other facets. The facets model has come out of our work with public servants from across different countries, and is a work in progress, with a number of hypotheses still to be fully tested.

Our aim is to help make practical sense of innovation for public servants, and so we value hearing from practitioners about their experiences and whether we’re hitting the right note. If you have any feedback, we welcome your comments, or you may wish to share your thoughts with us by email or on Twitter.

[1] Definition of enhancement https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/enhancement