Building experimentalist governance in Latvia

This is a guest post from Johannes Mikonnen of Demos Helsinki, a partner in our recent work with the Latvian public sector.

The world in which we live today calls for governments to find solutions to the most pressing challenges, and governments are falling short. Experimentation offers one particularly promising way for navigating the uncertainty and the rapidly changing circumstances of the 21st century. The Innovation Lab of the Latvian government embraced the transformative potential of experimentation and teamed up with independent think tank Demos Helsinki and the OPSI to conduct the new approach throughout the government. As a first step, and in conjunction with the OPSI scan of the innovation system of the Latvian public sector, Demos Helsinki produced a list of experimentation guidelines for the Latvian public sector. In this guest blog Johannes Mikkonen of Demos Helsinki offers a preview.

21st Century Government is Experimentalist

During the COVID-19 crisis, governments have been forced to implement policies without a solid experience of their impact. Not having a knowledge base to rely on, governments have had to turn to the rationale of trial and error, in other words, to develop experimental responses.

COVID-19 constitutes only a taste of the challenges that the future holds. Climate crises and developments like digitalisation, increasing global mobility, and demographic changes will require governments to change the ways they operate. Governments globally are recognizing the value of integrating systematic experimentation into their core functions. Over the last decade, countries like Finland, Canada, and the United Kingdom have been leading the way in creating experimental models for the public sector. Among those, Latvia also wants to be one step ahead and meet the challenges of the 21st century through experimentation.

The transformative approach to experimentation in Latvia

Experimentation is not a new topic in Latvia. However, it has so far been explored mainly as an opportunity to improve incrementally established practices. This means that a whole set of possibilities remain untapped. To fulfill its potential, experimentation should be linked to the core activities and strategic objectives of the Public Administration.

This ambitious goal and approach were defined in a co-creative process with the emerging community of experimentalists in the Latvian public sector. Our collaboration resulted in a series of guidelines that celebrate the benefits of the approach. The guidelines also define different types of experiments and suggest the many ways they can enhance policy-making in Latvia.

Also, these guidelines provide practical tools and methods on how to encourage a culture of experimentation in governance, and how to conduct and implement experiments from preparation to validating to communicating the results.

Experiments come in different forms and shapes

An experiment is a structured process of trying out policy ideas to enable learning and iteration before scaling takes place. Experimentation offers governments opportunities to create effective, people-centered policies and services by facilitating engagement and co-creation with a wide range of stakeholders throughout the process. It mitigates risks by testing solutions before significant investments have been made. Using experimentation helps create evidence-based policies and enables quick learning in early phases by revealing what works and what does not.

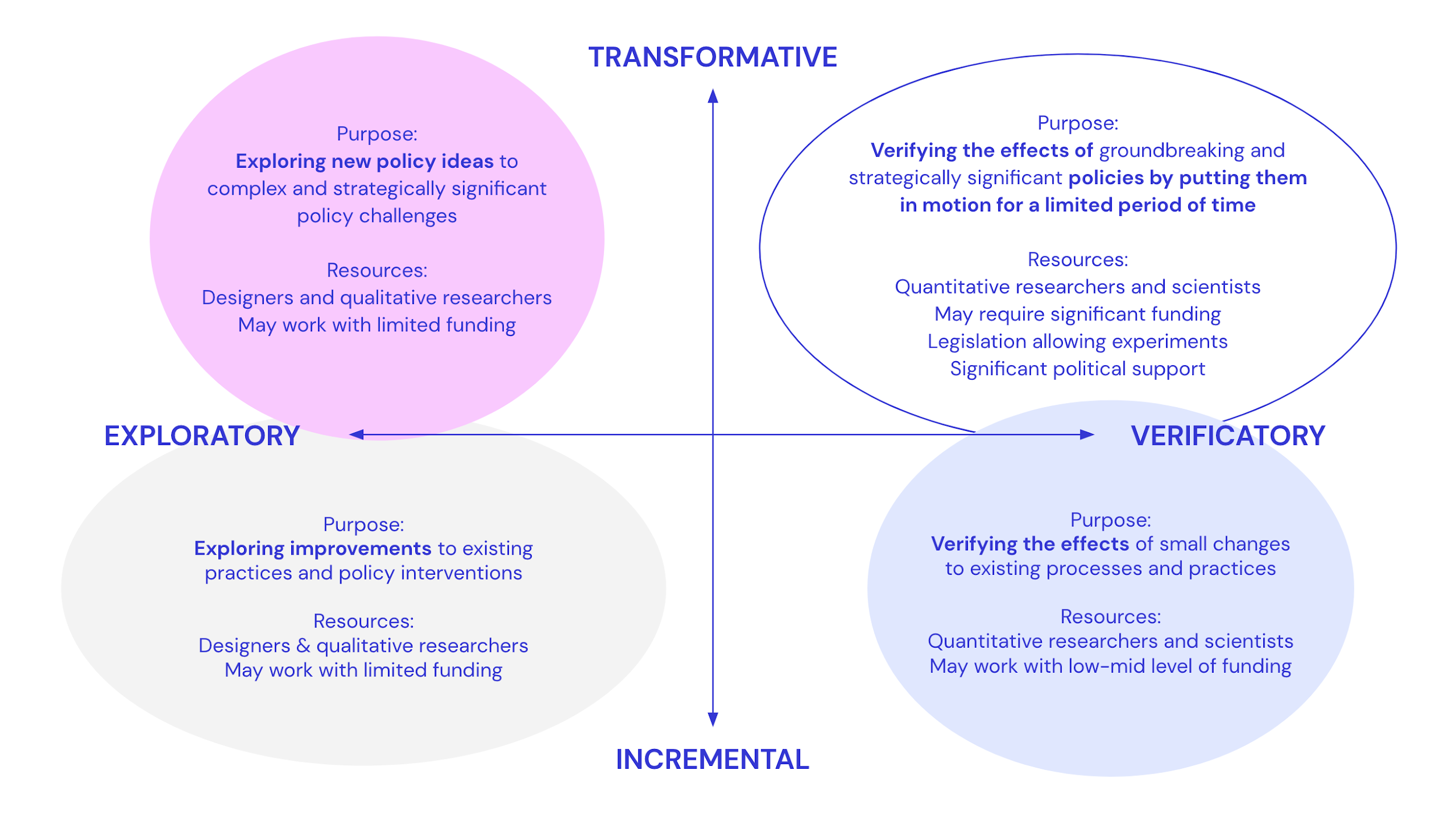

Experiments can be based on a variety of different types, tools and approaches. To make sense of this variety in the guidelines, we developed a typology of the different experiments, using their purpose as the main distinction. Does the experiment help us to explore or verify the effectiveness of different options?

Exploratory experiments can be used when the nature of the problem (and thus the corresponding solution) is unclear. Methods that help us to explore different directions are especially useful at earlier stages of development when there are significant levels of uncertainty around the policy problem and the potential solutions, for example prototyping and rapid cycle testing.

Verificatory experiments are best suited for when there is preliminary evidence to support that the planned intervention, big or small, could have a measurable impact. Examples of commonly used methods for verificatory experiments include randomised control trials (RCT), nimble RCTs, and A/B testing.

Experiments do not only vary in terms of purpose. They also seek to initiate change on different levels. Some experiments look to improve the efficiency or effectiveness of current practices, which often results in incremental changes that can have a significant impact. However, experiments that look to enable transformative change, which prompt rethinking of how pertinent issues are framed and solved in more fundamental ways, are even more powerful.

Selecting the type of experiment depends on its purpose and the resources available. The typology below aimed to support Latvian civil servants to select the most appropriate one.

The phases outlined below equip any Latvian civil servant to design and implement an experiment. While these phases may differ based on the type of experiment being conducted, the main features of the process remain the same. The tools and methods of different phases can be found here.

| 0. Preparing | 1. Identifying | 2. Exploring | 3. Testing | 4. Validating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify experimentation objective and goals Form an experimentation team Identify key stakeholders and partners and plan their engagement Prepare a communication and documentation plan | Explore root causes, existing evidence, and best practices related to the selected societal challenge Develop experimentation idea(s) and select experiment Define learning outcomes of the experiment | Engage stakeholders in exploring the challenge and potential experiment ideas further Develop ways of testing your hypotheses on a small scale Define ways to collect data throughout the experiment | Create a risk assessment, avoidance and prevention plan Implement small-scale test(s) Define an implementation plan for the experiment Develop a plan of how to make use of the upcoming results | Implement the experiment Evaluate the results of the experiment Share the results with the relevant organizations Identify next steps |

Cultivating experimentation culture

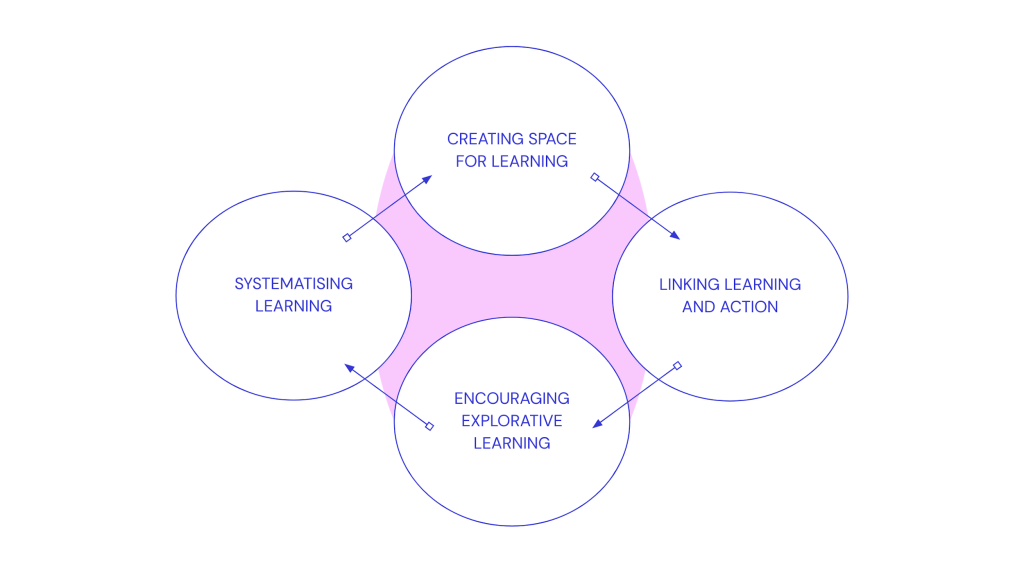

During this collaboration, the team identified several bottlenecks that hinder the utilisation of experimentation in its full potential, such as rigid legal processes and lack of experimentation capabilities. In order to start finding the solutions for the identified barriers and pursuing a transformative approach to experimentation in Latvia, the first step is to create an encouraging space and culture.

Experimentation culture means that civil servants and decision-makers feel safe to express and try non-conventional ideas without facing immediate and debilitating criticism. It refers to the possibility of talking openly about failures in order to ensure learning and progress.

The hard, but ultimately rewarding and important work in Latvia continues to this day. Creating an experimentation culture and grasping the opportunities of experimentation require changes in the everyday practices and in mindsets. Experimentation means using new methods and developing new operation models in rapidly changing circumstances. It also means remaining humble and open in the face of the unknown, as setbacks and failure become essential ingredients of learning—thus leading to more informed action. The ambitious approach of transformative experimentation enables the Latvian government to reap the benefits of a continuous capacity to innovate. Through experimentation, Latvia not only gets a head start by pro-actively preparing its response to future threats, but it also makes a commitment to understanding, acknowledging, and, ultimately, better serving its people.

The whole publication is available on the Latvian State Chancellory site.

For further inquiries:

- Johannes Mikkonen Demos Helsinki, [email protected]

- Inese Brokane-Zarane, the State Chancellery’s Innovation Laboratory, [email protected]