Crafting an innovation profession for government

This blog was authored by Dr. Christian Bason, CEO of the Danish Design Centre in Copenhagen, formerly Director of MindLab, the Danish government’s innovation team, and a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Agile Governance.

Reflecting on the OPSI Innovation Facets model

There is nothing as practical as good theory, goes the saying in academia. But in the public sector we too often see nice theoretical frameworks without any true underpinning in reality – and without much potential for making an impact.

Sometimes, however, you see a conceptual model that has the potential to be truly useful. This November I had the pleasure of contributing with some remarks to that end, the annual public sector innovation conference ‘Innovation in Government: Steps, leaps and bounds’ organised by OPSI in Paris.

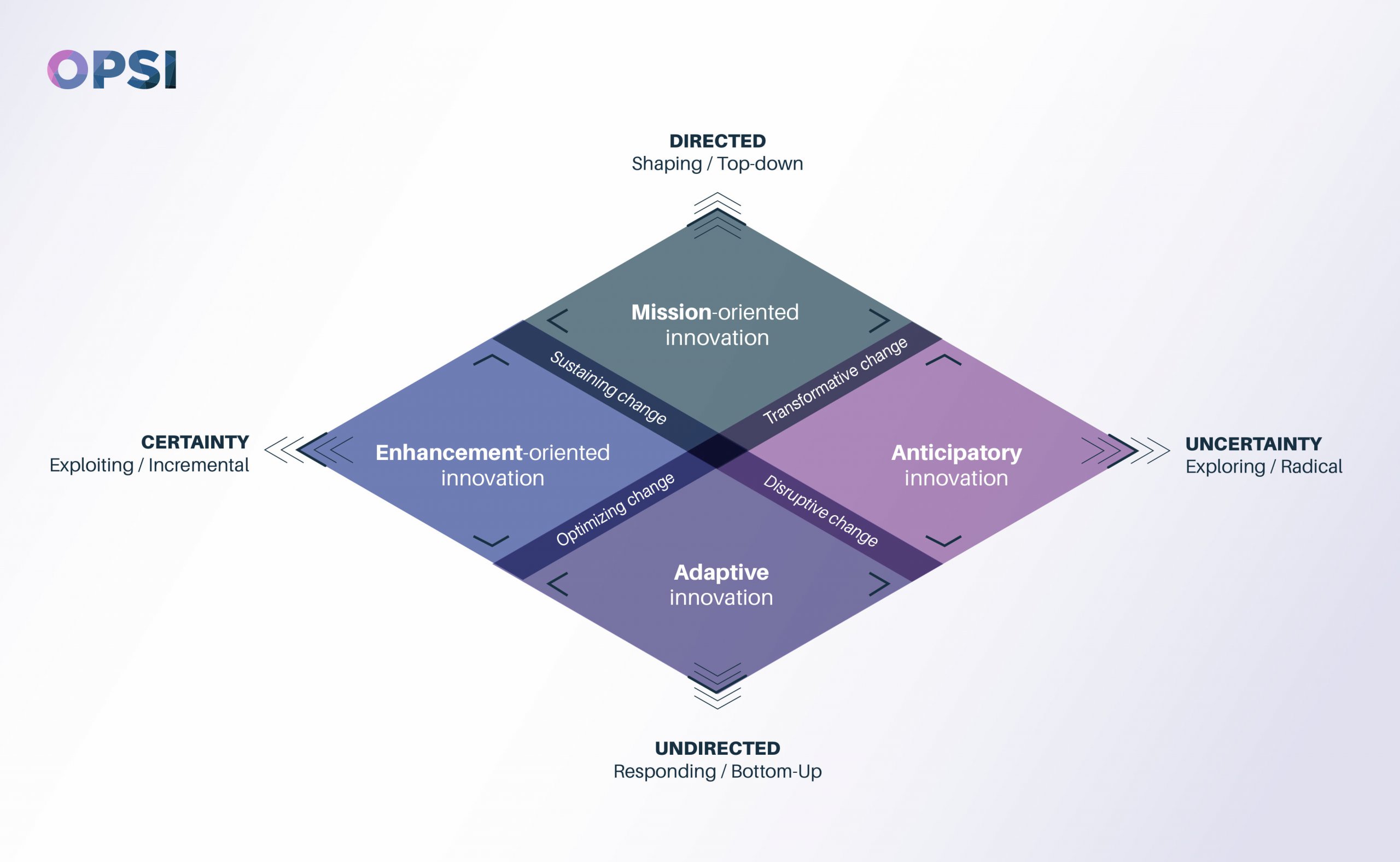

Beforehand, I had the chance to review the organisation’s new model for thinking about the roles government can play in advancing innovation in society – inside and outside the public sector. The model lays out a framework across two dimensions – one considering the degree of uncertainty facing government innovators, the other capturing whether the approach to innovation is proactive or reactive. The resulting two-by-two frame offers some useful continua upon which government action on innovation can play out.

As with any new suggestion, there are reasons for praise as well as reasons for pushing back – suggesting ways to advance the work further and identifying pitfalls to avoid.

Praise: The value of a holistic model

On balance, the OPSI Innovation Facets model should be praised for a number useful characteristics. Namely four stand out:

- The model introduces a logically structured common language, which builds on previous work in the field, and thus advances the development of public sector innovation as a practice with shared terms and concepts. This is in dire need if we wish to move the field towards a true profession of its own.

- The model is holistic and, as its authors assert, multidextrous, as it captures a wide range of the aspects (or facets, as it were) of innovation in public sector. In that sense it is in the vein of Bessant, Tidd and Pavits “4P” innovation model, Jocelyne Bourgon’s “New synthesis”, Snowden & Boone’s “A Leader’s Framework for Decision-Making” or my own “4C Public sector innovation ecosystem”. The strength of such models is that they become placeholders for wider considerations of organisational and processual responses to their different dimensions.

- The OPSI Innovation Facets model is further useful because it essentially matches innovation needs, triggered by a given context, with approaches and tools, providing adaptability and flexibility in various types of environments, most notably depending on the perceived degree of risk.

- Finally, I agree with the authors that the framework will be a useful guide to inform decision-makers, enabling them to decide on how to balance their programme or innovation portfolio across its dimensions. Leaders can then better understand when and how to be pro-active in stimulating innovation investments, and when to take a more responsive stance.

I believe these traits will make the model useful to a range of actors and stakeholders, including senior managers and strategists in government, experts and practitioners at different levels, human resources professionals focusing on skills development, and indeed for academics, researchers and external consultants working with and for the public sector.

Potential applications abound

The OPSI Innovation Facets model should now stand the test of such practitioners putting it into practice. I could see it used to various ends, including:

- Devising innovation strategy

- Responding to new external challenges

- Creating an innovation portfolio, making balanced investments

- Skills development

- For project design, guiding choice of tools and methodologies

- Communicating an organisation’s innovation efforts internally and externally

I can report that we are already looking into the application of the model at the Danish Design Centre, where we are advising the Danish Business Authority on balancing pro-active and re-active processes within business regulation.

Push: Five challenges and areas for further development

The OPSI Innovation Facets model offers a powerful starting point, but it is not immune to some issues that could benefit from further elaboration. Here are five challenges which might better be viewed as an agenda for further debate and potential development:

- Linking more clearly to types of public value: The model could make more explicit which types of public value are best served by the different approaches to innovation? I would see different types of public value to include better outcomes, productivity improvements, better service experiences for users, democracy/legitimacy/participation, and finally enhanced employee satisfaction. Would it be possible to identify whether different types of innovation “facets” tend to advance some types of public value rather than others?

- Identify clearly the methodologies linked to the facets: What are the more precise capabilities, approaches, tools, methods, skills, organisation and governance models associated with the four overall facets? How would a public sector organisation seek to create a comprehensive programme of training and capacity building in order to address them?

- How might the model advance democratic legitimacy? One of the most pressing challenges of our time is to build more democratic legitimacy and trust between citizens and their public institutions. Issues of participation, engagement, responsiveness and feelings of being seen and heard are at the forefront of the political agenda in many countries – not least across the OECD. How could the model work to address some of these issues, which are essentially a pressing need for “innovation of democracy”?

- What does the model imply for the interaction between business and government? In my perspective, one of the great flaws of our current public administrations is their inability to engage ambitiously and usefully with the private sector in the post-New Public Management era. We are yet to find models that positively unleash the particular roles and unique characteristics of these two key domains in society. Stimulating better, faster and more fruitful collaboration with the private sector, enabling innovation and sustainable growth in a context of rapid technological change and continued globalization isn’t too much to demand from the the OPSI Innovation Facets model. It would be fascinating to see how this could be further elaborated.

- Learning mechanism: How might public organisations applying the model build systematic processes of data gathering and collective learning at the heart of the model? For any organisation, applying a novel framework will require not only implementation but continuous adaptation and enhancement of performance over time. At the Danish Design Centre we have recently explored the structure of such learning mechanisms in collaboration with the United Nations Development Program, including how to digitally underpin them. I believe there is much more to do, especially in more complex and distributed public-purpose organisations, to understand how to drive learning in the context of innovation. Here, is an opportunity to be seized.

Towards the next generation public sector innovation agenda

Looking forward I think the most exciting current application of the OPSI Innovation Facets model is on the upper and right-hand side where governments seek to deal with more risk and with anticipating change in view of the emerging future.

This is also reflected in the World Economic Forum’s recent emphasis on agile governance as a critically important field, which explores the implications of new technology, new business models in the private sector, and regulatory and governance responses from public organisations. In that context our work in WEF has shown that we need much clearer terminologies and approaches when it comes to public/private experiments and “sandboxes” – something that resonates well with OPSI’s most welcome contribution to the still-emerging profession of public sector innovation.