Innovation labs can’t do it all…

Innovation labs often help accelerate innovation and change in government. They create the space for new ideas to take root and grow, supporting stakeholders to identify and tackle the root cause of problems, not just treat the symptoms. Their approach usually tries to support the development of new policies, services, process or product innovations and demonstrates the impact of working in new ways (e.g. responsive services, improved access, cost and time savings).

Through work with the Latvian State Chancellery’s Innovation Lab, supported by DG Reform of the European Commission, we’re exploring how to accelerate the work and impact of the Latvian Innovation Lab, while simultaneously taking a systemic approach to innovation through a public sector innovation strategy. Through this project, we’ve witnessed the impact that innovation labs can produce, while also confronting a public sector system that isn’t naturally conducive to innovation. This blog explores the tension between the role and expectations of innovation labs and the complexity of systems change in the public sector, much of which is out of the realm of responsibility of a lone innovation lab.

What do Innovation labs do?

Innovation labs typically offer a guided process for innovation projects that use methods such as design sprints or behavioural science. They invite public sector teams that are struggling to solve a problem (e.g. making tax returns more user-friendly, increasing school registration) and guide them through exploring and defining the problem, to generating, iterating, prototyping and testing potential solutions (prototypes) before scaling. Labs often support teams to tackle public challenges where current policies and interventions fall short – whether they lack a cross-cutting approach, have become ineffective, or require a fresh approach. Through this guided approach, they simultaneously help equip participating teams with the skills to apply these innovation methodologies in their own teams and thus widen and deepen innovation capacity and capability across the public sector.

However, the public sector system in which labs operate in tends to not be very friendly to innovation. In a recent session with the Latvian Innovation Lab, networks and executives, the former head of Northern Ireland’s Innovation Lab, Malcolm Beattie described how innovators and innovation labs confront the larger environment of the public sector:

Innovators are like mushrooms trying to grow in a system of grids and boxes

Malcolm Beattie

Innovation labs help protect innovators from the immune response of the public sector system

Innovation labs often provide a space for innovation to grow (the mushrooms) in creative and bottom-up ways, where the outcomes are often hard to predict at the start and success is not always a guarantee. The public sector, on the other hand, is a restrictive system which often suffocates or even attacks innovation in boxes of regulatory requirements, procurement rules, hiring criteria, audit and political cycles – the opposite of a nourishing, organic environment.

Rowan Conway and co-authors in “From design thinking to systems change”, introduce the phenomenon of an immune response of hierarchical, bureaucratic systems, which works insidiously against innovation, particularly those represented by systems thinking and design approach. Bureaucratic processes rightly promote rules, regulations, and conformity to protect integrity, promote security of public funds and accuracy. However, it is a blunt instrument and thus detects innovation as variance to the norm, which needs to be viewed with suspicion and investigated. Such tendencies are often demonstrated in public sector audits which identify financial risks of innovation without considering the costs and inefficiencies of the status quo and the outcomes of innovative solutions. These attitudes are deeply engrained in the culture of organisations and can have a severely limiting effect on the concept of innovation and its associated initiatives. In this context, innovation labs work to create a space that is relatively protected from the immune response; enabling innovation to occur despite the system.

Expectations of innovation labs are often unrealistic: innovation labs are only one player in the logic of change

As innovation labs are only one part of a large system, it is tough for them to meet the expectations that often come from senior management, public servants and stakeholders that they be solely responsible for making innovation and change happen in the public sector. If innovation labs are expected to do it all – they will fail.

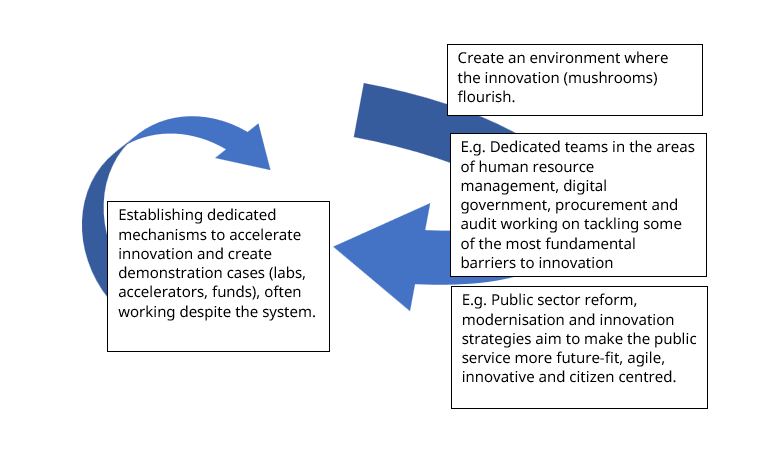

For public sector innovation to flourish, governments need to consider a blend of explicit, dedicated mechanisms for innovation to grow, while simultaneously improving the fundamental governance structures of the public sector to make them more conducive to growth and innovation (such as changing HR rules, new procurement rules, improving digital infrastructure and data sharing).

Mechanisms, like innovation labs, can help support the bottom-up, demonstrator cases of innovation while this systems change is ongoing. Once the public sector system has reached the stage of stimulating and supporting innovation, the innovation lab may no longer be needed (innovation becomes a norm rather than an exception and is embedded in the daily life of the public service).

Balancing organic innovation with systems change in practice

To ensure innovation labs aren’t alone in this journey, a systems approach to innovation is needed, often directed through innovation strategies and reform efforts (e.g. modernisation plans, government programmes, transformation plans). These strategic approaches often call on a wide range of government actors to take an active role in making the public sector more conducive to innovation, such as:

- Centre of Government (coordinating initiatives)

- Ministries of Finance (financing innovation)

- Public service schools (building capacities and skills to innovate)

- Human resource experts (recruiting and retaining a future fit and qualified workforce)

- Audit offices (creating space to learn from mistakes and reflect on impact)

- Senior management and the political layer (setting the strategic direction of innovation and encouraging innovative behaviours)

- Procurement offices (creating space for flexible procurement and challenge-based procurement)

There is no perfect formula for stimulating innovation in government, but diversifying efforts with a mix of explicit innovation supports (e.g. labs, accelerators, contests show on the left column below) and systems wide supports (e.g. human resource reforms, digital infrastructure etc.) can help Throughout this process, it is essential for political and top executive leadership to support both these areas while “walking the talk” of innovation by encouraging innovative approaches within their teams, decision-making, processes and ways of working.

| Explicit innovation supports | Systems-wide supports for innovation |

| Innovation labs (providing dedicated spaces, processes, and training for innovation to occur, often relying on creative processes. E.g. Latvia, Chile, Portugal, Romania, UK policy lab. Innovation accelerators (cohorts of teams or companies who receive intensive, time-limited support and mentorship to build capacity and seed funding for prototype development) (e.g. Digital Democracy Accelerator, Canada’s IDEaS). Idea contests (opportunities for innovators or users to propose potential solutions to specific problems / thematic areas, with winning proposals receiving funding to develop solutions) (e.g. German’s Policy Lab Idea Contest). Innovation incubators (dedicated resourcing, space and support for innovative solution development) (E.g. France’s Digital Service Incubator). Innovation networks (communities of innovators, often providing a safe space for learning, idea sharing and collaboration) e.g. Romania, Latvia, Chile, Flanders. Mission-oriented innovation programmes that target complex problems in a designated timeline. | Embedding innovative and participatory methods into strategic planning, policy, and service design requirements. E.g. use of strategic foresight, design, user research, co-creation, stakeholder engagement). This often requires action from the Centre of Government to ensure these methods are embedding into planning systems. Building an innovative workforce through human resource management. E.g. introducing innovative criteria into competency framework, integrating skills, competencies, learning and performance management criteria related to innovation. Building the necessary digital infrastructure and data sharing platforms. Enabling innovative and horizontal ways of working through interoperable digital technology and data. Enabling the procurement of innovative solutions. Creating procurement mechanisms that can help governments procure innovative solutions such as those that don’t already exist in the market, innovation experts (e.g. designers) that can’t be recruited directly in the public sector or solutions that require phased development. Creating more agility and understanding of impact through monitoring and evaluation. Leveraging internal audit, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to constantly gather data on whether solutions are delivering impact. |

rough these blends of supports governments can enable flagship and demonstrator innovation projects that show that these methods can deliver tangible while simultaneously making the public sector system less rigid and more conducive to creative growth while impact.