Innovation Portfolio Management in the Public, Non-profit Sector

A matter of methods, mindsets, and mechanisms.

Why innovation portfolio management?

Innovation Portfolio Management has long been used by the private sector to improve returns on investments. The potential of using the same approach to improve social returns is huge.

A growing number of OECD Member countries and organisations in the international development sector are exploring innovation portfolio management. Follow, for example, the exciting work of OECD-OPSI, OECD INDEF, CGIAR, UNDP, UNICEF and others.

Based on these examples, our experience (helping organisations adopt innovation portfolio management) and academic research into the private sector, we have found that innovation portfolio management is not as simple as deciding what goes IN a portfolio.

Rather, innovation portfolio management requires a transformation of how a development organisation works (so they can USE a portfolio approach).

This article helps practitioners with that change by sharing 1) a framework – mindsets, mechanisms and methods, and 2) an ideal process to introduce, test and institutionalise innovation portfolio management.

Benefits of active innovation portfolio management

We conducted a literature review on innovation portfolio management in the private sector and drew on the findings from this 2019 DFID review. The findings suggest that active portfolio management:

- Strengthens organisational agility and alignment to priorities: Creates transparency in how innovations (and capabilities) align with the key priorities

- Improves transparent and quality decision making: Encourages clear procedures and criteria for decision making, which leads to more repeatable and trustworthy decisions

- Facilitates monitoring, risk management and prioritisation: Helps compare investments to see which should be boosted, adapted or stopped, and encourages balancing ‘safer bets’ with higher risk innovations

- Improves organisational performance and learning: Increases awareness of organisational performance (what’s going well, where can we improve), and generates insights that can support organisational learning

- Facilitates scaling pathways: Enables an organisation to keep track of innovations’ trajectories to increase impact at appropriate scales.

When we correlate ‘organisational performance’ to ‘social impact’ (the currency of public, non-profit sector performance), it’s persuasive that intentional portfolio management increases the likelihood of impact and value for money of public, non-profit sector investments – something funders are increasingly demanding.

A public non-profit sector portfolio will, of course, have boundaries to its levels of influence. Working on wicked challenges in complex, adaptive systems means that no matter how well an organisation manages their portfolio, they will be but one part of the broader system. Humility and collaboration are key.

What supports a portfolio approach?

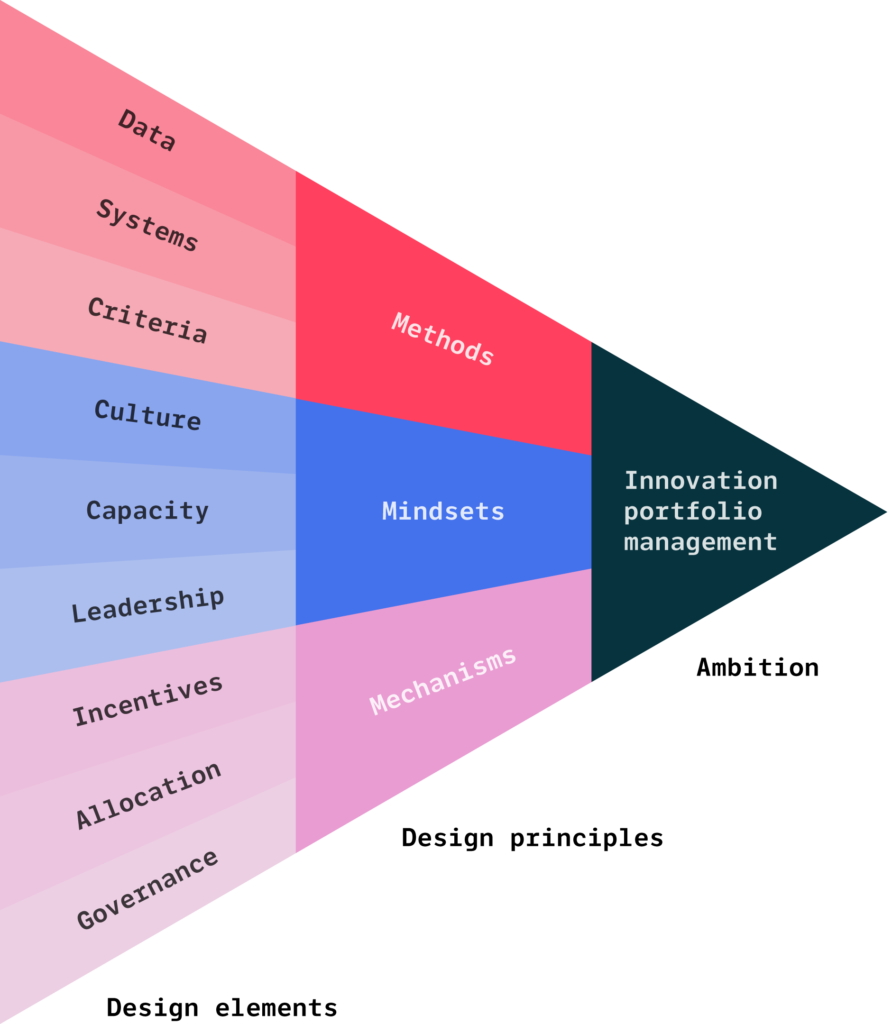

We believe that for any innovation portfolio management approach to ‘work’, it needs to consider a triumvirate of methods, mindsets and mechanisms[1] (Fig. 1).

What constitutes the ‘right’ combination of methods, mindsets and mechanisms depends on the overall innovation portfolio management ambition which refers to the vision, mission and goals associated with the portfolio and its management. A clear intent[2] will guide decisions to help you to reach the goal.

Method

Data: What information will be collected and used for decision making? Portfolio management requires data to make decisions on. What data is needed depends on the innovation portfolio ambition and overall organisation mission. For example, if an organisation wants to show how its innovation portfolio is targeting the Sustainable Development Goals in multiple countries, then this data needs to be collected.

Systems: How to ensure data is accurate, timely and relevant? Functional data collection systems and structures are needed to ensure data is collected in a uniform and systematic way. This is important to be able to aggregate information and to generate the relevant analytics to support decision-making. Systems should be able to ensure the quality of data, for example by integrating quality assurance.

Criteria: What criteria will you use to analyse and compare your portfolio? Decide these early and differentiate between strategic criteria and tactical criteria. Strategic criteria include a focus on deepening impact vs. reaching new constituencies, exploration vs. optimisation intent and others. Tactical, hard criteria include research and development data, risk categories (such as programmatic risk or risk of stagnation), impact potential, or expected return on investment. Tactical, soft criteria could include opinions of influential stakeholders, or gut feelings of managers or decision-makers.

Mindset

Culture: How does the organisational culture support portfolio management? It’s important to consider mindsets and take an organisational culture change lens. The organisational innovation culture includes creativity, risk appetite and commitment to learn from failure. Additional factors to consider are organisational dynamics (like favouring new innovation work over the hard work of adopting innovation), commitment to a problem and the openness to iterate, and existing myths (e.g. that a portfolio approach increases top-down decision making).

Capacity: How do we strengthen knowledge, skills and attitudes in the organisation? The capacities that can support portfolio management include (i) a clear understanding of what innovation portfolio management is, and what it tries to achieve, (ii) belief that the organisation has the ability to develop and implement innovation portfolio management practices in a meaningful way, (iii) constructive behavior towards the changes that are needed for successful portfolio management and (iv) a commitment to adopt the practices by the organisation.

Leadership: How do senior and middle leaders support the change? Leadership support is critical. Successful portfolio management requires leaders that empower employees and invite inclusive strategic reflections on portfolio distribution and performance at regular intervals. Leadership should ‘lead by example’.

Mechanisms

Incentives: How do organisational rules, procedures and policies support the behaviors and mindsets needed? Existing organisational systems and processes can either support or undermine desired efforts. For example, this could be lack of flexibility in planning, budgeting or procurement processes, donor restrictions to where investments can be made, or individual or team performance appraisals that encourage behaviours at odds from those shared above.

Allocation: How will you allocate financial, human and other resources across the portfolio? Deciding a strategy in advance will make it easier to make decisions in the moment. Think about the balance between lower and higher programmatic risk, or distribution of investment along innovation stages. For example, consider making smaller investments in a wide range of innovations at early stages and larger investments in less innovations at later stages.

Governance: Who will make decisions on portfolio allocation? Define the roles and responsibilities of the people involved, as well as governance mechanisms for decision making. What existing business processes can be leveraged to integrate portfolio mapping, reviews, sensemaking and decision-making in such a way that it empowers employees across different levels in the organisation.

How to set up and dynamically manage an innovation portfolio?

We (Marc, Emma and Ben) all work with international development organisations to set up innovation portfolio management systems.

We’ve found that despite the best will in the world, innovation portfolio management processes don’t stick if they’re not aligned with core processes and embedded in how the organisation (and it’s people) think and act.

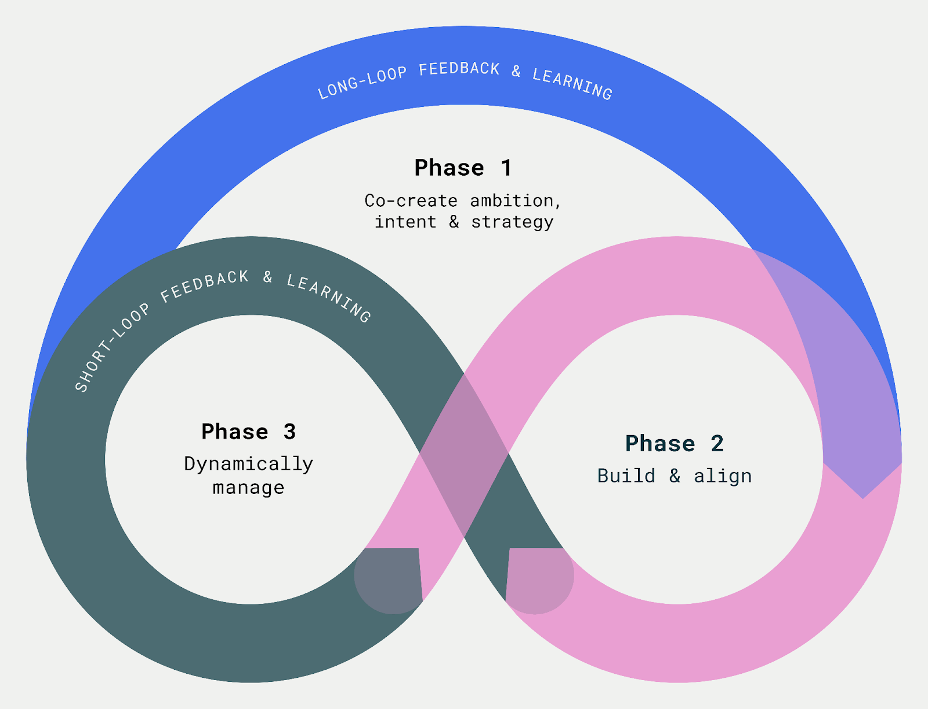

To avoid innovation portfolio management initiatives to be one-off activities, we propose this three-step process to help readers interested in designing processes that last. Of course, this is an ideal process, and in practice, steps will often be skipped or combined. Take what’s useful!

To set up and implement an innovation portfolio, we suggest a phased approach that puts reflection, learning and adaptation at its heart, with both long- and short-feedback loops (Fig. 2).

The long loops are opportunities to review and revise the overall innovation portfolio management ambition, intent and strategy. The shorter loops are focused on building or re-aligning the methods, mindsets and mechanisms in order to meet the innovation portfolio ambition.

Phase 1: Co-create strategic underpinnings for innovation investments

At the start of this work, it is essential to co-design and co-construct the overall organisational capacity, narrative, ambition for innovation writ-large and its portfolio management. It’s important to align organisational commitment, mandate and boundaries with the ambition of portfolio management. We build on a process developed with OECD and tested with bilaterals (written up in the Stanford Social Innovation Review) to map how the current organisational functions might support or interrupt the ambitions of portfolio management.

Key elements to consider during phase 1 include:

Method

- Data: Agree on data to be collected and how that will support decision-making, strategic communication. Consider the needs of different groups of innovation portfolio managers.

- Systems: Inventory of existing data infrastructure and systems (e.g. finance, human resources, monitoring and evaluation) and consider how these support meaningful innovation portfolio management.

- Criteria: Determine a meaningful mix of existing hard and soft criteria for decision-making and prioritisation. Discuss the consequences of, for example, when will an innovation be stopped? When will funding (and people/ time) be moved?

Mindset

- Culture: Assess the existing organisational performance and innovation culture and explore what resistance to and support for an innovation portfolio management approach could be expected

- Capacity: Share what an innovation portfolio management approach is, how it can support the organisation in achieving its goals and the role of different staff to support different forms of innovation.

- Leadership Bring leaders from different levels on board, so they can champion the innovation portfolio management approach and critically review if the portfolio delivers against expectations.

Mechanisms

- Incentives: Map how incumbent rules, procedures and policies support the ambition of portfolio management and identify what may need to change, in what order.

- Allocation: Once stakeholders identified the most important criteria for innovation investments, develop a tailored model that serves as a tool for resource allocation strategies.

- Governance: Either leverage existing business processes to ensure innovation portfolio mapping, review, sensemaking and adjustments happen on a regular basis, or establish new ones with as little as possible additional friction.

Phase 2: Map, ‘sensemake’ and align the current portfolio to intent

Now comes the moment to apply the theoretical portfolio concepts and draft strategies and criteria to real innovations.

First, map the existing innovations to the criteria identified. Next, have a conversation about allocation, interdependence and gaps. Continue to engage internal and external stakeholders around the agreed upon feedback- and decision-points.

Key elements to consider during phase 2 include:

Method

- Data: Collect innovation data and assess whether the right type (and quality) of innovation data is collected to inform timely management decisions, and what data gaps and opportunities have emerged.

- Systems: Design, enhance and/or deploy basic data collection and analyses tools and systems to map existing innovations onto the themes and criteria to get a visual of your existing portfolio.

- Criteria: Would the current set of decision-making criteria have the desired effect? Consider the implications for your innovation pipeline, teams and partnerships.

Mindsets

- Culture: Build or re-align components of the organisational culture to grow levels of connectedness, trust, knowledge of others’ work, comfort with uncertainty and risks, curiosity, ability to learn, and share the learning internally and externally.

- Capacity: Keep telling the story around the innovation portfolio management ambitions, including how this approach will improve social impact, enable investments in systemic work and address the risk of stagnation for the organisation. Check in on the capacity needed to make this happen and consider how to engage existing staff.,

- Leadership: Grow a community of change agents among senior managers to build alliances between champions, share stories and build trust and confidence.

Mechanisms

- Incentives: Consider the mechanisms at individual, team and the organisation level that can be maintained, changed or developed to align incentives with the innovation portfolio management ambition and intent.

- Allocation: Do your current investments match your strategic intent? How would you change or add allocations to reflect your intent? How are existing interventions interlinked and reinforcing?

- Governance: Modify (or tap into) reporting, learning, planning and budgeting cycles and governance mechanism so innovation portfolio management is or becomes part of business as usual.

Phase 3: Dynamically manage and evolve the portfolio

Portfolio management is a dynamic, iterative process. Consider sensemaking with stakeholders from the broader system for learning moments, to help understand (and forge) interdependencies, look for unforeseen opportunities and consequences, and emerging needs. It’s important to put learning and adapting at the core of innovation portfolio management.

Key things to consider during phase 3 include:

- The state of the system. What has changed, what opportunities are emerging, what blockers have been found, what else is happening?

- The progress of the portfolio. What is showing signs of change, what is hard, what synergies have been helpful, what’s missing, what have we learned about our assumptions or hypotheses?

- The implications of this information. Suggestions (not decisions) for what to start, stop and continue, ideas for other resources, networks or partners that could be mobilised or engaged with to effect greater change?

Embrace innovation portfolio management

An innovation portfolio management approach is not a plug-and-play product or solution. It requires investment in methods, mindsets and mechanisms to ensure it supports (rather than obstructs) organisations in achieving their innovation intent and organisational goals.

Innovation portfolio management is a practical way to optimise for social impact in complexity and we are excited to see the dents this intentionality could bring to the world. We see an increasing desire of organisations in the public, non-profit domain to manage their portfolio of innovations and interventions in a more intentional way as a means to optimise their contribution to positive societal impacts.

[1]This triumvirate comes from Brink’s ‘Behavioural Innovation’ model

[2] The concept ‘Intent’ is also emphasised by others advocating portfolio approaches such as Climate KIC, UNDP and Chora Foundation. ‘Intent’ is broader than the measurable objectives often found in development programmes, which are underpinned by assumptions of predictability and linearity