OECD Survey Says: What mission-oriented innovators really want

One of the biggest challenges in taking a mission-oriented innovation approach is operationalising the ambitions in practice. While many missions have been announced – including missions to tackle climate change, enhance equality, reduce poverty, and many others – there is a lack of analytical reflection of what drives missions to success.

To answer this question, the OECD Mission Action Lab and the Danish Design Centre conducted a survey in December 2021. Two hundred and twenty seven people from 40 countries shared their insights and surprising discoveries about what mission owners really want and need.

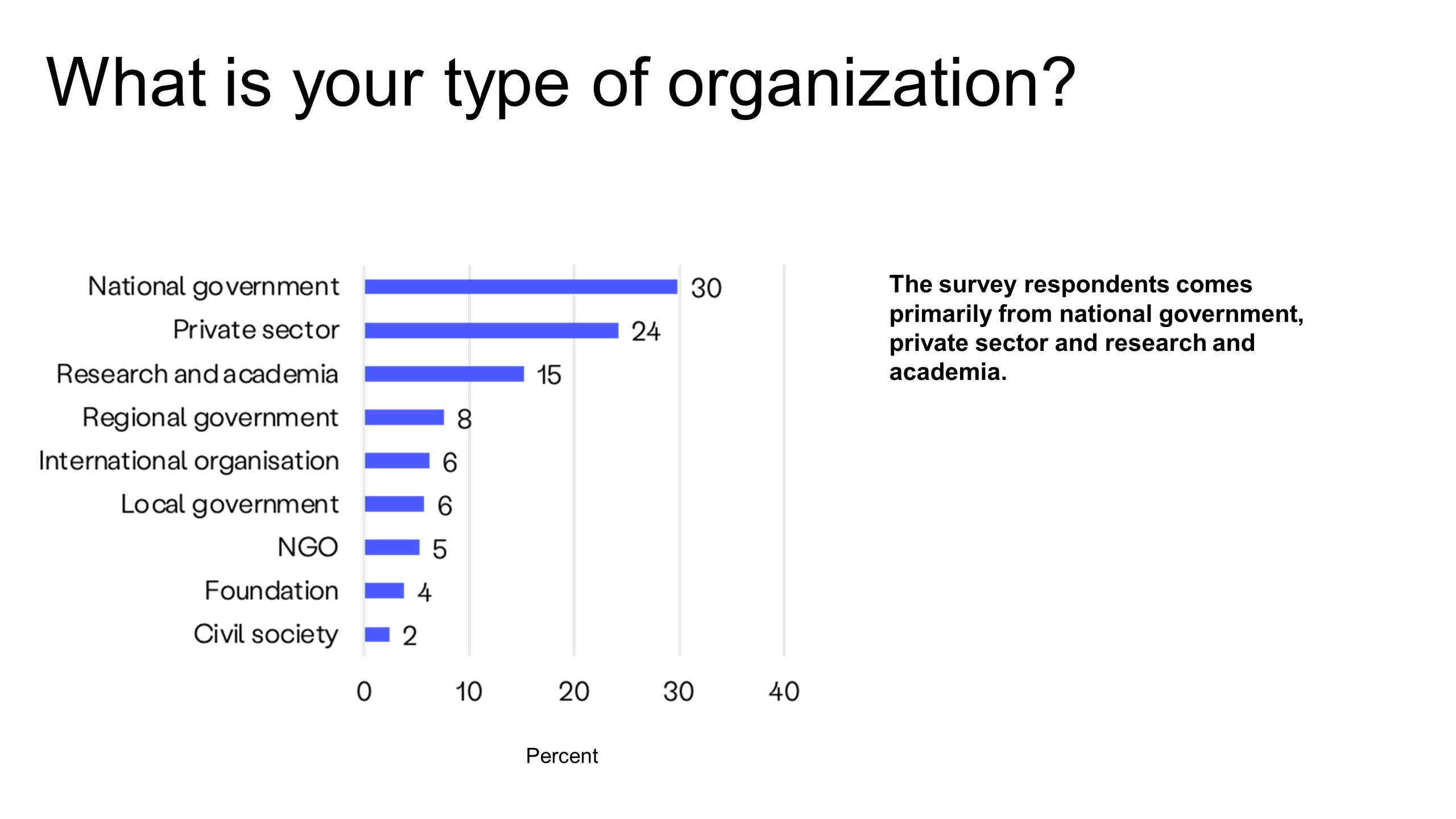

The majority of respondents were public sector actors, followed by private sector actors and researchers and academics, among others. In addition, most respondents reported being currently involved with a specific mission, particularly in the health, social, environmental and technology policy domains.

Check out our detailed summary of the results.

We need more: bottom-up AND top-down approaches

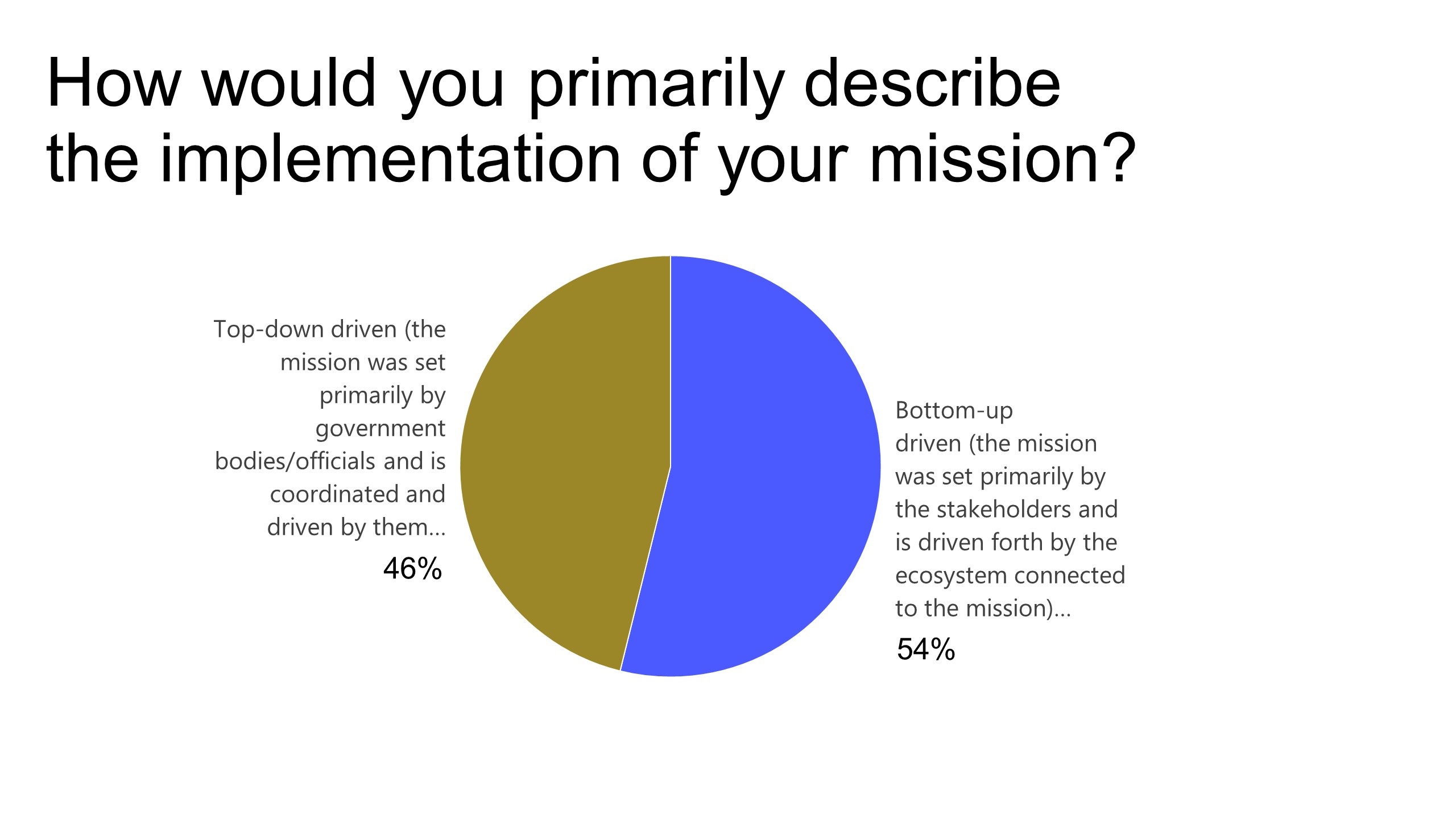

The establishment and commitment-building phase of missions are often considered a top-down process, with ambitious goals announced with much fanfare by leaders at the top of public and private sector organisations. However, surprisingly, a majority of respondents indicated that their mission is driven bottom-up, in other words driven by a collective of partners connected to the mission.

There is a lack of understanding from innovators on how to contribute to a quickly growing number of missions. The results are endless reports or, at best, PR stunts that often neither help the intended target nor makes tangible steps towards a solution. The most cost-effective innovations would be possible by embracing non-government actors, which can move flexibly.

Survey respondent

This begs the question: what is the right way to set and deliver a mission? Respondents were divided: 54% stated that they use a mission-oriented approach driven by bottom-up action, while 46% work on missions driven by top down directives. Our study and follow-up workshop indicates that the most critical aspects for missions to be successful are:

- Top-down policy and strategic coordination

- Bottom-up experimentation involving an ecosystem of actors

- Capacity to manage a diverse portfolio of activities

The results confirm that the key feature of missions is that they can combine both top-down policy and strategic coordination, as well bottom-up experimentation involving an ecosystem of actors.

There is a major risk of placing too much emphasis on the mission’s success being driven by a charismatic and powerful individual, and not effectively underpinned by infrastructure, governance and oversight.

Survey respondent

We need more: evaluation but few are doing it…

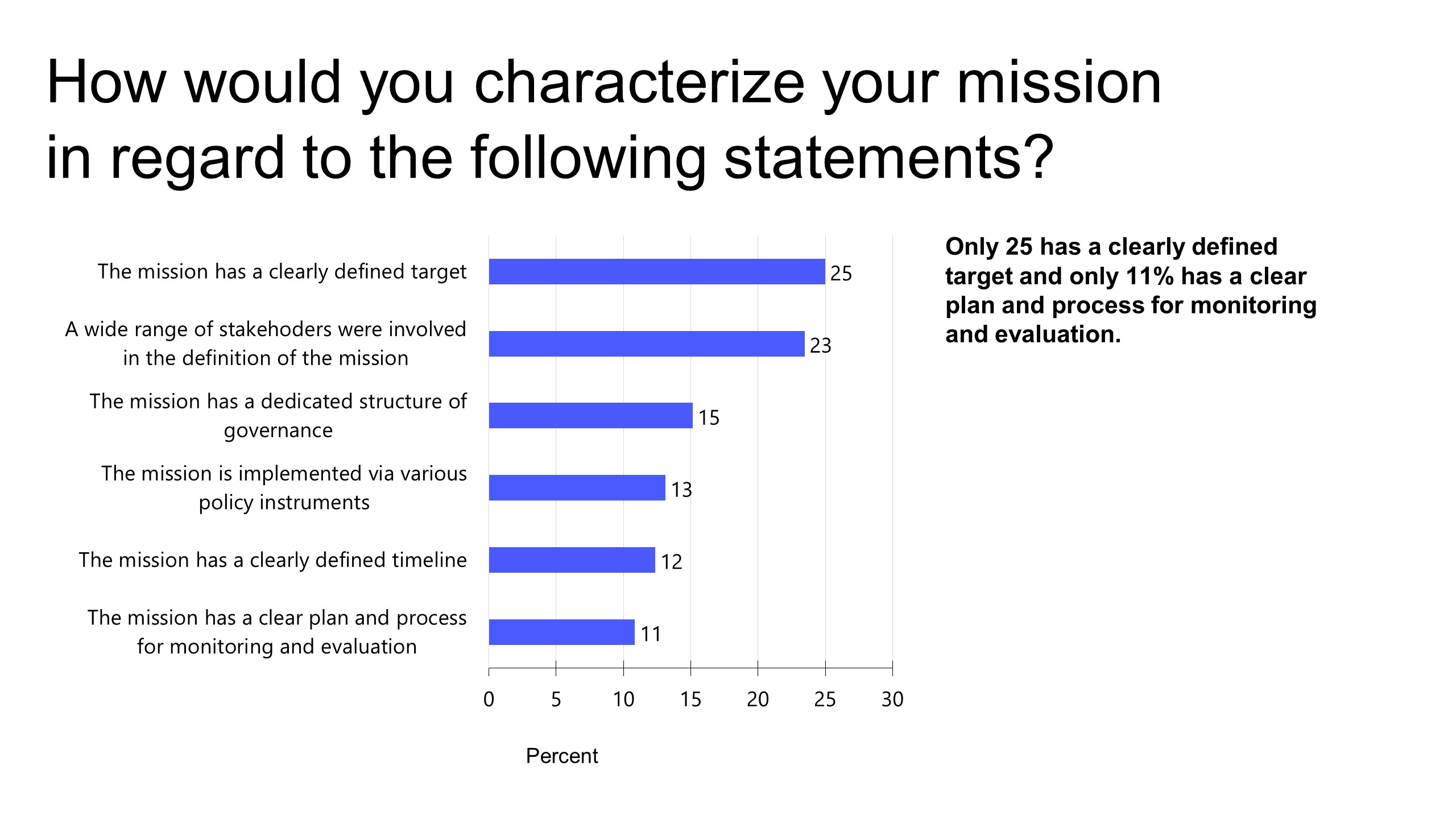

Missions are long-term, ambitious outcomes well beyond the lifespan of many individual projects, programmes or even individual professional and political careers. Think climate change! As much as we would like to solve it within one lifetime, the reality is it will take many more projects, programmes, leaders and stakeholders to find solutions. New approaches require experimentation and testing of entirely new solutions, collaboration models and governance structures. However, many evaluation processes measure impact and effectiveness based on status quo baselines and outdated assumptions about what “success” looks like. For instance, evaluations focussed on “value for money” are too narrow to capture the behaviour change, collaboration and innovation goals targeted by missions. Indeed, only 11% of survey respondents indicated that they have a plan and process to measure and evaluate their mission.

How can we know whether we are on track or have achieved our goal if there aren’t any set metrics to measure against? It therefore becomes clear that missions require different evaluation methods, including ways to evaluate the early-stages and reflective processes to inform subsequent actions.

The main challenge is monitoring progress and performance during the implementation phase which can be lengthy – including identifying whether the mission is on track to achieve its objective; and monitoring whether a change in scope will impact on delivery (or not).

Survey respondent

We need more: collaboration and collective intelligence

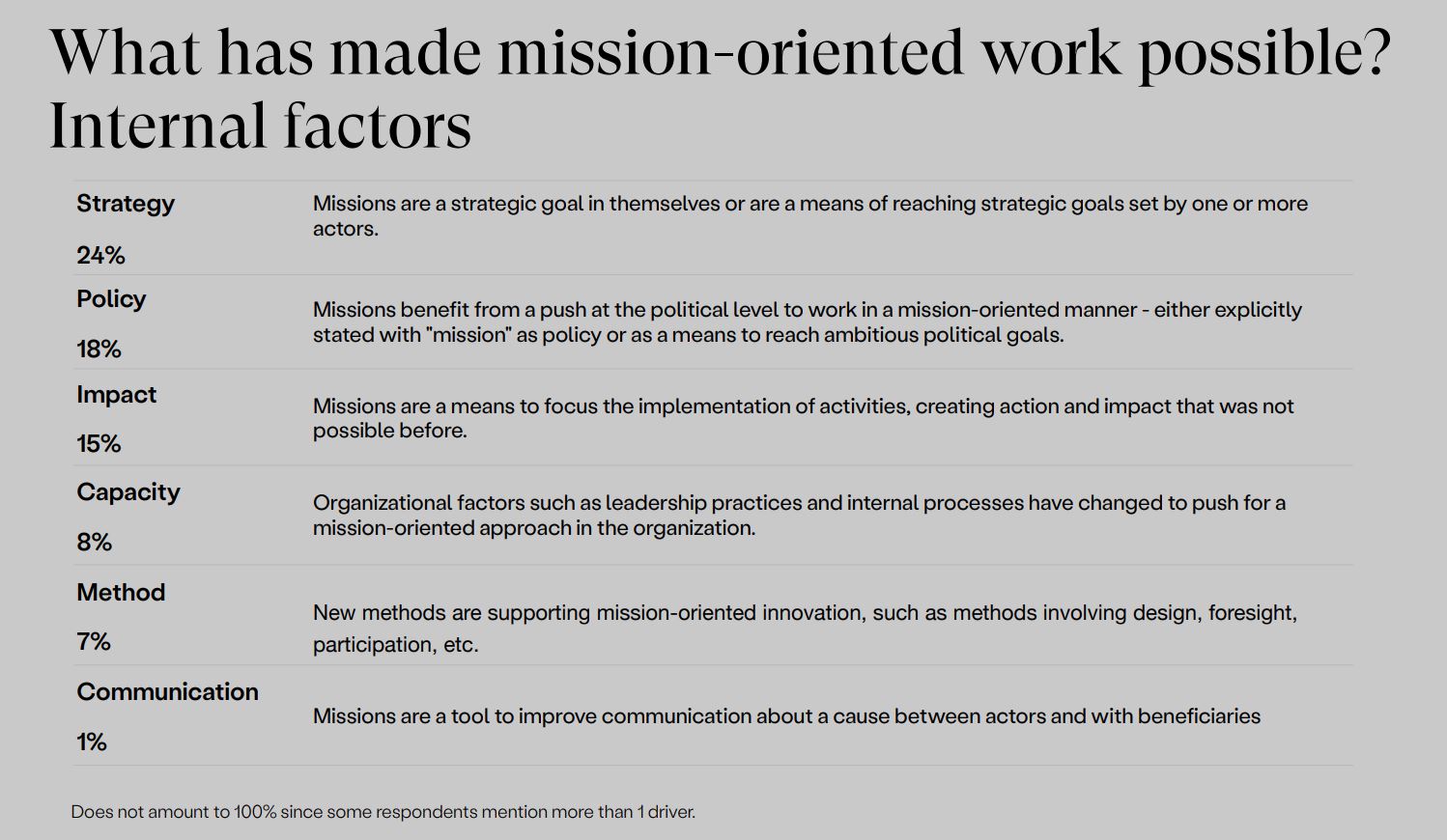

One third of survey respondents ranked new collaboration methods as the main ingredient for making mission work possible. While this is unsurprising, given the complex and cross-disciplinary nature of missions, that same complexity makes collaborations, in practice, quite difficult. Mission collaboration involves knowledge building and learning across organisations and policy silos, the development and engagement of innovation ecosystems, and multi-level governance coordination – as missions cannot be achieved by one individual or organisation acting alone.

There is a lack of tools to facilitate collaboration across many-to-many collaborative relationships.

Survey respondent

While many traditional management structures and relationship management practices are oriented around a central actor or gatekeeper, missions require a “many-to-many relationship management” approach. This implies a trade-off: centralised ownership to decide exactly how the mission will proceed is lost, while a collaborative environment is gained. Collaboration means faster exchange of ideas, better integration of knowledge across policy areas and more diverse solutions.

We need convening, facilitative and sense-making capabilities, approaches to understanding the mission system from multiple perspectives, and behaviour change analytical tools.

Survey respondent

We need more: attention to the long game!

The substance of missions are not solvable overnight. Challenges such as carbon neutrality, clean oceans and the reduction of cancer cases will require sustained effort over a long period of time – a time frame that extends beyond most budget, policy, funding and election cycles. Governance structures are often on a short time horizon and those accountable come and go. However, this creates an accountability dilemma for long-term missions; it creates a bias toward the incumbent systems and makes it challenging for mission champions to obtain the long-term resources and time commitment needed for driving forward an ambitious mission. Without sustained momentum, missions are one crisis away from being pushed down on the agenda.

We need governance ensuring continued focus on the mission, not subprojects.

Survey respondent

What’s next?

The specific needs identified in the survey inform the research agenda of the Mission Action Lab, a joint collaboration of the OECD Governance Directorate, the Science, Technology, and Innovation Directorate and the Development Co-operation Directorate. The research agenda of the Lab includes a focus on mission governance, portfolios of innovation supporting missions and mission evaluation – all of which will be further refined and directed by the needs identified in this survey. If you wish to learn more about the Lab or get involved, email us at [email protected]. And don’t forget to read the full summary of the Mission-Oriented Innovation Needs Survey here.