The Power of Exploration: Improved Market Exploration and Experiments in the Face of Post-COVID Government Spending Challenges

As we emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic, our governments are beginning to examine how to fill the gap in public finances this massive crisis has created. We are standing at a cross-road, facing difficult questions: are hard budget cuts inevitable or is it time to promote another way of doing things within government? How can we increase the value of our tax money and, at the same time, deal with government spending challenges? How can we deliver better services and better value for (tax) money for the sake of our citizens and organisations?

My initial idea was to suggest putting a stop to all current projects, to remove civil servants from their usual working methods and to go back to the drawing board: start the exploration phase over again. While tempting, putting this into practice would clearly require a rather radical approach. With over 20 years of experience in the public sector, including five years of working in innovation, I am persuaded that innovation is all too often overlooked as we capitulate to our routine ways of handling projects. In this article, I will argue that at a time of limited government spending, greater and better market exploration, including experiments, is an essential prerequisite for any successful government strategy.

The status quo

Civil servants often work across many different sectors, with a broad range of expertise. Nonetheless, it is impossible to be an expert in all possible solutions and technologies, today more than ever. As a result, civil servants often dive into the project implementation stage without having explored all possible solutions. Moreover, the typically overly cautious and bureaucratic contracts favoured in the public sector demonstrate that we do not really trust or fully understand the expertise of private companies. This explosive combination leads to a contradictory situation: public services do not trust private companies, yet we buy from them – and that without testing their proposed solutions!

The required change

Innovation speaker, Stephen Shapiro, and his notorious ‘baggage claim video’ helps to crystallise this contradiction and underlines the need for effective innovation. Through his example we understand the need to first obtain an in-depth understanding of an underlying problem before attempting to solve it. For me, and the entire Nido innovation lab team, his video remains exemplary in understanding that innovation starts by correctly framing the problem upfront. However, due to our work environment and culture we are taught from an early age that effective problem solving means delivering quick-fix solutions. This behaviour is further intensified in the public sector by internal bureaucracy procedures which slow down business renewal.

We are used to starting projects with some research on possible solutions, such as (inter)national benchmarks, and to curiously checking what our national and international peers are doing. After gathering some inspiration, we write a tender in which we try to grasp the technology and requirements needed for a successful implementation. On top of that, a procurement team will generally help to exclude all possible risks through elaborate procedures and strict advice. Only the bigger companies – that have the capacity to understand regulations for timely delivery of a correct offer, including all documents – will be able to routinely participate in such tenders. These ‘usual suspects’, however, disappoint us most of the time. De facto, the public tendering process has turned into something merely legal. Are civil servants genuinely persuaded that writing everything in the procurement tender is the only way to success? We avoid dialogues with companies out of fear of looking partisan. Yet, by fooling ourselves to be bound by procedure and to doing ‘the right thing’, we kill innovation.

Another big challenge for public services is money and budget management. We regularly spend large sums of money on projects that often are not as successful as hoped. We also tend to spend excessive amounts on products or services that can, in fact, be purchased for less. Being open to collaborations with newer, younger and more modern companies could help us end this vicious cycle. These companies tend to be more enthusiastic and eager to suggest better and cheaper solutions. While civil servants are usually well placed to know what is needed for their work, an expert can be an added value. The person tasked to look for solutions is oftentimes unable to see the real issue or does not dare to point to the real problem. A problem normally does not persist due to lack of solutions, but the inability to connect the negative experience of an end-user with its cause. External third-parties can help discover the missing links for effective progress.

In the light of all of these issues, I dare to propose the following:

- Do not begin with clear plans and projects; start with market exploration and experiments.

- Allow yourself to be inspired by the variety of possible solutions to your problem. That process will help you detect the actual problem(s) you want to solve.

- Build your business case with a limited budget; only ask management for a budget increase once you demonstrated that the solution will work.

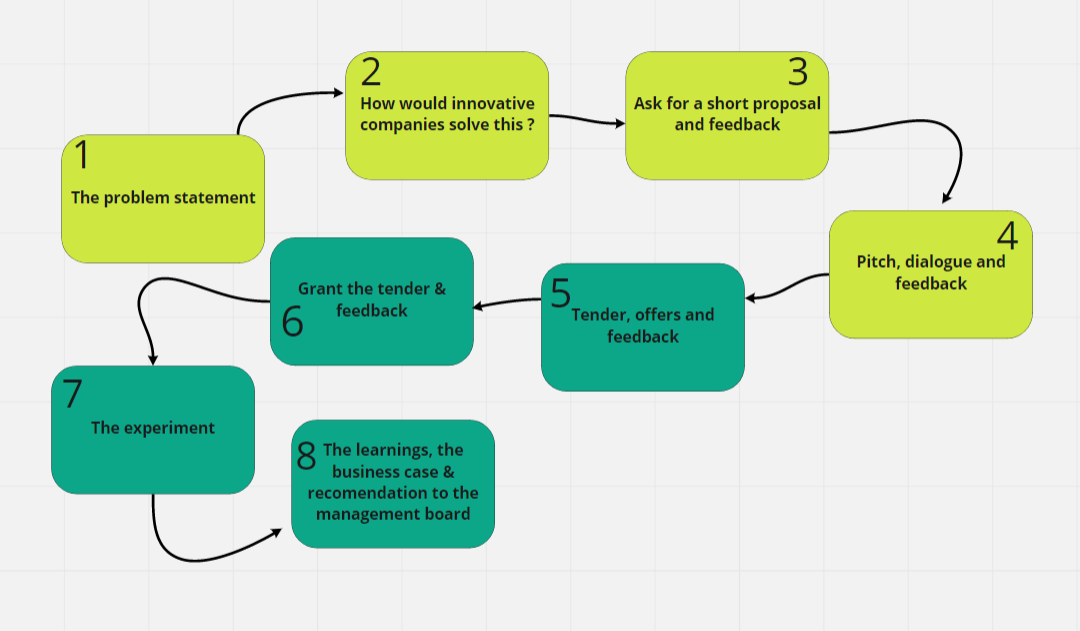

The steps to make it happen

Let me set out some step-by-step advice on how to start a new project:

Step 1: Write a problem statement, make a stakeholder analysis and ask the opinion of your audience/clients/ users.

Step 2: Let innovative companies, both small and big, look over your problem statement and incorporate their feedback and inputs. Make it clear that you want to know how they would solve your problem. Allow all to participate and make it easy: a short phone call, an informal email etc.

Step 3: Ask companies with interesting approaches for a short first-solution proposal.

While you probably have a good solution in mind, you have yet to see all possibilities. I advise you to put your ideas on hold and keep an open mind. Filter the discovered solutions through the following criteria:

- Will this solution solve my problem?

- How successful is this solution?

- Is it innovative or just more of the same?

Step 4: Invite only the companies with the most interesting solutions for a pitch, presentation or dialogue. Ask questions and give them the opportunity to ask questions in return. Don’t forget to give honest feedback to companies whose solutions you are less interested in and thank them for their participation.

Further filter the solutions through these criteria:

- What is the rough estimated cost for full implementation?

- What can be tested during an experiment?

- What is the price of the experiment although limited to a limited budget e.g. 30k (they might do it for less)?

- Is the team capable and motivated?

Stop at step 4 if you only want a strict market consultation. Draft your recommendation for the management board.

Step 5: Submit an offer to participate in the tender to the companies with the best solutions and give them extensive feedback on their pitch or presentation. This ensures that you will only receive interesting offers.

Step 6: Grant the tender to the most innovative and interesting experiment(s). Don’t be persuaded to simply take the offer that is most likely to succeed or the cheapest; remember that you want to learn about new possibilities as opposed to merely re-testing a well-known product. Don’t forget to give honest feedback to the companies who have presented a solution you are less interested in. Thank them for taking the time to participate.

Step 7: Perform the experiment. Remember that you are working with a limited budget. Therefore, only test what is really important and avoid losing time and money on gimmicks. Test the solution on end-users – their feedback is what matters at the end of the day. Focus on the Minimum viable product and the lessons you are learning.

Step 8:

- If successful: draft a recommendation for the management board. If you have a good working solution in MVP, ask for the necessary budget. If your experiment is successful, dare to take the next step: make a business case to persuade your management with the knowledge you have gained throughout this process.

- If failed: restart the process. You will have learned from the selection procedure and experiment, and can now take wiser, more knowledgeable decisions. The first attempt is not a failure, but brings you one step closer to your suitable solution. Remember that you have successfully managed to avoid a failing project. Always try to understand what exactly made the approach fail: did the team not deliver? Does the solution simply not fit? Or did you not capture all aspects of the problem?

Ultimately, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. You and the company you chose will test the most important assumptions with a limited budget.

We wish you lots of success! Do let us know if our advice has helped, or inspired you to make a change.

Who or what is Nido?

Nido, innovation lab at FPS BoSa enables innovation in the Belgian public sector by supporting civil servants in their quest for change. Our initiative “Government Buys Innovation” aims to create an interactive marketplace for a modern version of public procurement, centred on the active search for innovative solutions that are already available on the market. By reconsidering the way the public and the private sectors interact, Nido aspires to transform public entities into pioneers for new creative ideas, modernising within Belgium and beyond, to the benefit of both companies and citizens.

Nido undertakes small budget, open-market research and experimentation before launching projects, in order to respect government spending limits. Experimentation is promoted as the first step to exploring possible innovative solutions in order to avoid major projects failing, and taxpayers’ money being wasted.

It is impossible for the public sector to have sufficient expertise across the full range of solutions and technologies they might use. Therefore, it is often impossible to know in advance whether a solution will work and be fit for purpose before purchasing it. Experimentation is thus key to ensuring a solution will be successful and worth the investment.

GBI is a unique approach to public procurement, changing the role of civil servants from problem solvers to problem experts, and teaching them to approach new solutions with an open mind.

Frédéric Baervoets is the manager of the Belgian innovation lab Nido, part of the federal public service Strategy and support. This article reflects the personal views of the author.