Hedging your bets: taking a portfolio approach to innovation

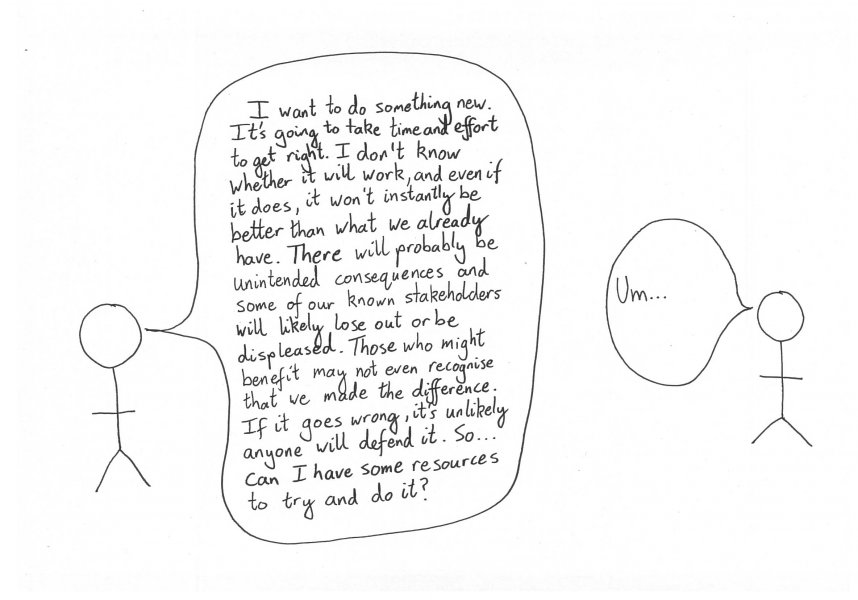

“I want to do something new. It’s going to take time and effort to get right. I don’t know whether it will work, and even if it does, it won’t instantly be better than what we already have. There will probably be unintended consequences and some of our known stakeholders will likely lose out or be displeased. Those who might benefit may not even recognise that we made the difference. If it goes wrong, it’s unlikely anyone will defend it. So … can I have some resources to try and do it?”

If someone said that to you, would you say yes? And if such a novel project does offer guarantees or certainties, then those promises are likely to be misleading (or simply untrue). Is it any wonder that innovation can often be a hard sell, even when the existing situation is not ideal or clearly needs to change? While whatever exists now may not be good enough, at least it has the advantage of already existing and delivering something. On the other hand, in the face of uncertainty, innovation can seem like a gamble, something that many public sector leaders are justifiably wary of.

So what can be done to make innovation a better bet?

Innovation can be an investment, but it is by no means a sure bet

Undertaking innovation should be an investment: the process and act of innovation is dedicating resources, time and decision-making/leadership attention towards trying something different in the hope of achieving a better outcome (whether it be greater effectiveness, greater efficiency, a new way of solving a problem, or as a means of learning about an emerging issue).

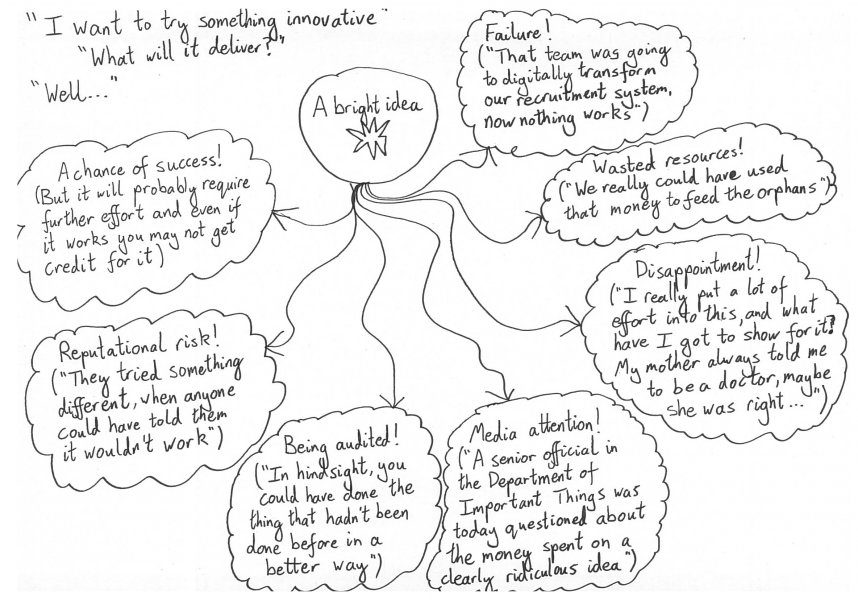

Yet innovation is an uncertain investment. There is no guarantee about whether any single innovation will work, how it will work, or what the unintended or unanticipated consequences might be.

This means innovation is a somewhat risky proposition. It is not easy to do, it will often clash with existing ways of doing things, it will require changing behaviours and practices, and it might not even achieve what was promised. (Of course staying with the status quo is also risky, but the risks that come with doing something different are often more apparent or tangible.)

No wonder then, that it can be a struggle to get resources or approval for innovation. Viewed on its own, a single innovative project offers the chance to invest (time, effort, attention, resources) in something that may well not work.

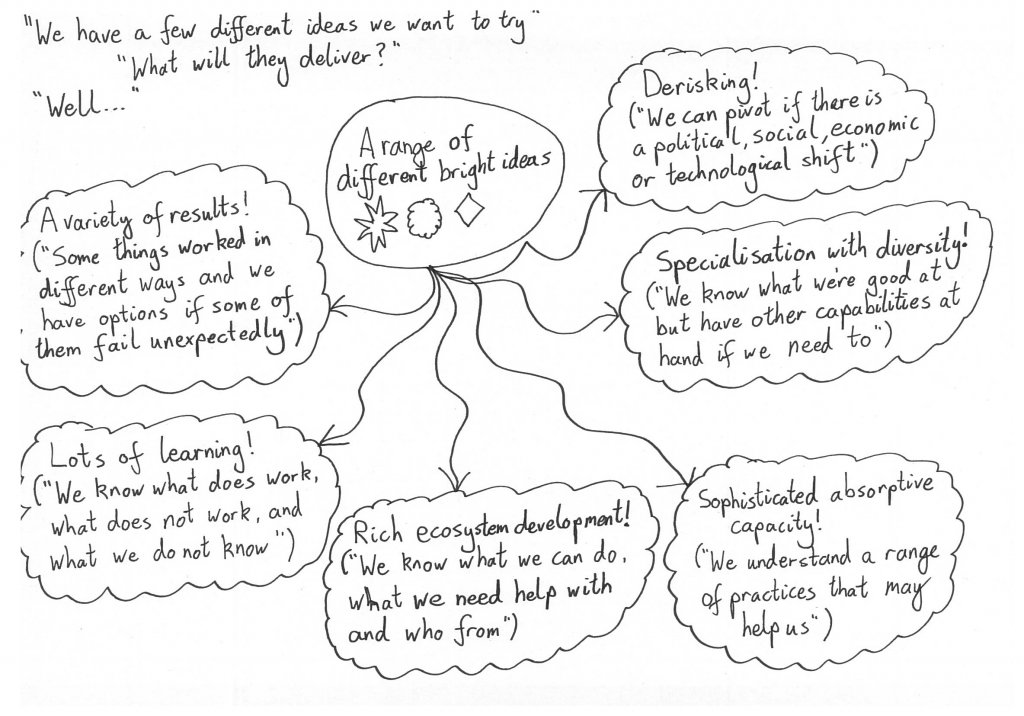

A portfolio of multiple projects offers better odds

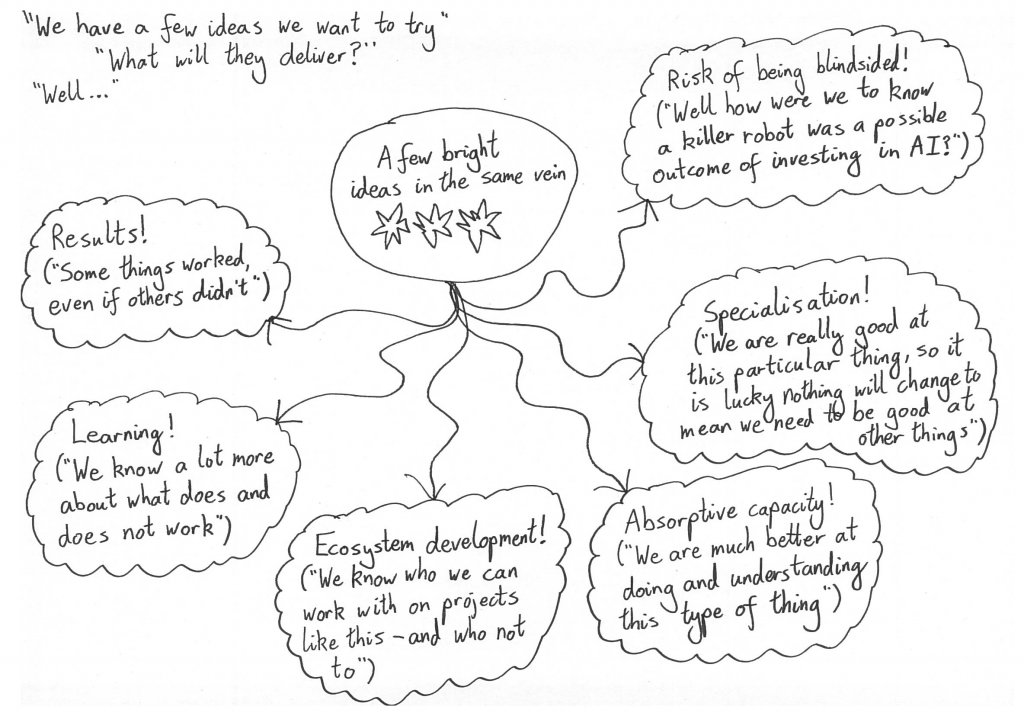

In the financial investment world, a portfolio offers the chance to spread risk across a range of investments. Multiple investments mitigate the chance of loss, because if one investment fails others might still succeed.

A portfolio approach is even more relevant for innovation. By investing in a number of innovations, the chances of getting a desired or useful result are increased. Of course, there are costs in having more than one project, but when viewed from a portfolio perspective it is easier to see these additional costs as investments, rather than one-off bets with no guarantee of success, as it is more likely that some of them will pay off. From a strategic perspective, a portfolio of projects is a better bet than a lone project, especially if the operating environment is uncertain and you cannot be confident about where (or when) you might need to have an innovative response.

Yet if all of the projects in a portfolio are similar, they may also share the same risks that they will not work. Many similar projects can offer benefits over a single project, but if there is a lack of diversity in the types of projects then a portfolio may still be a risky bet.

A diverse portfolio offers even better odds

In an investment portfolio, having a multiple investments helps to broaden your portfolio. However, an effective portfolio will also be spread across different investment types, as dependence on any one type leaves a vulnerability that all of that type will not work.

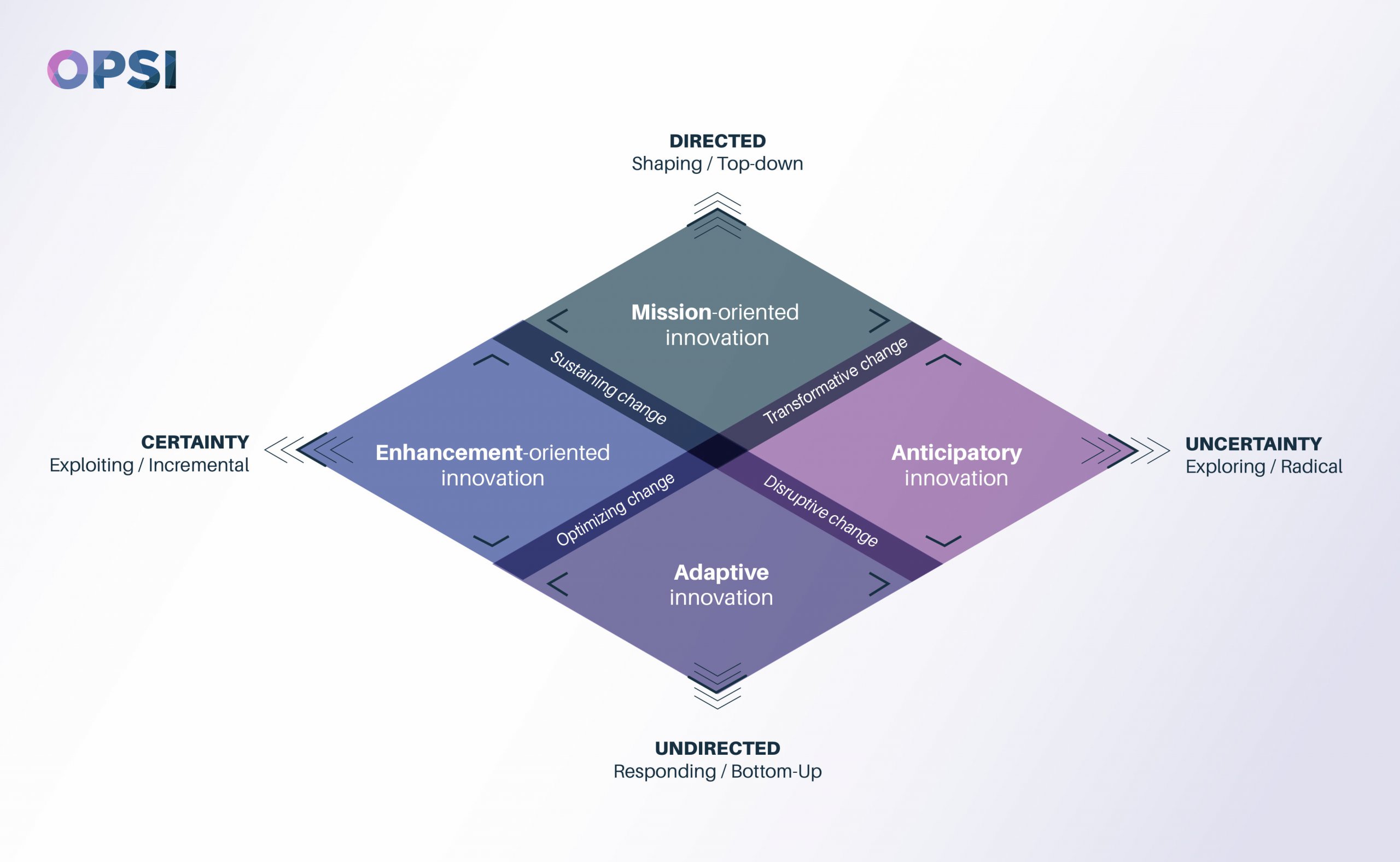

Similarly, for an innovation portfolio there also needs to be a diversity of types, not just a multiple of projects. One way to consider the spread of project types is to consider the different facets of innovation: enhancement-oriented innovation, mission-oriented innovation, adaptive innovation, and anticipatory innovation. A diverse portfolio reduces the risk involved and provides a richer set of potential returns. Diverse investments provide different options for a range of different futures.

By having a range of investments across the different facets of innovation activity, innovation becomes an easier sell, as there is a much greater likelihood of a payoff. On the flip side, it means that innovation needs a coordinated view, as a single individual is not going to be able to undertake or have a very diverse portfolio of public sector innovation. It is too hard for most individuals to run lots of different innovations at once, especially in a public sector context. A portfolio approach is therefore something that really needs to be viewed from the wider perspective of a team, an organisation, multiple organisations, or even across an entire sector or system. A diverse portfolio, and the attendant costs and efforts, is going to be harder to justify if seen from a narrow focus.

How do you develop a diverse portfolio?

Of course, it is easy to say that it is important to have a diverse portfolio (and it has been said – see the Declaration on Public Sector Innovation). But how can a diverse innovation portfolio be achieved in practice? It can be difficult enough doing one innovative project, let alone multiple ones.

Therefore, we are exploring how a diverse innovation portfolio can be supported. Most organisations will have some sort of portfolio already in place – it just may not be viewed or coordinated as such. So part of this work includes exploring why existing portfolios may be the way they are – what are the things that are currently driving innovation activity into the different facets? It is also about exploring how shifts in a portfolio can be managed, when priorities change and a different mix of innovation activity might be needed.

It is also about recognising that a single team or organisation may not want, or be able, to have a truly diverse portfolio – and that is okay. An organisation may want or need to specialise or it may not have a mandate that lets it go beyond one particular facet of innovation activity. In such cases, we hope the innovation facets and a portfolio approach can still be of use. We hope that it can be a tool for thinking about how and who to partner with, so as to connect with and share in the lessons from the portfolios of others (whether they be other teams, organisations, sectors or countries). Such a strategy can help mitigate some of the risks of innovating, as well as accelerating learning and building relationships that may help in the future. Such efforts are not costless, but if they are viewed from a portfolio perspective, they seem less like bets and more like investments that can result in real returns.

This is an area of ongoing investigation for us, and we are keen to hear from others about their experiences with their public sector innovation portfolios. What has your experience been? Does your public sector agency have an explicit innovation portfolio? If you have any feedback, we really value comments, or you may wish to share your thoughts with us by email or on Twitter.