Innovation facets and core values: how different forms of innovation can cause different reactions

Have new technologies made you reconsider what you hold dear? Has change or innovation ever come into conflict, or sat uncomfortably, with your core values? Why is it that we as individuals can react negatively to things that are supposed to be beneficial? This post explore why different forms of innovation can spur different reactions from people, and what that might mean for practitioners seeking to introduce novel initiatives.

We at OPSI think this is an important discussion as innovation is often associated with making things better, while the difficulties that can come with it are brushed over. Practitioners and public servants need to understand how and why different reactions to innovation can occur, in order to prepare for those reactions. And part of that is appreciating how innovation can touch upon the things that are central to our identity as individuals – our core values.

Innovation, by bringing in something new, forces us to consider the default settings that exist. Innovation can make us question things that we take for granted. We might think we know what our core values are, or which values take priority over others and which are immutable. Innovation can upset that, forcing us to consider what it is we really value and why. This can be a deeply personal and uncomfortable process, as it gets to fundamental questions of identity and belief. This is part of why, despite the benefits that innovation may bring, innovation can be unwelcome, as it makes us question assumed truths.

This post unpacks this issue and examines how the different forms of innovation can lead to different reactions and counter-reactions.

Core values for the public service: public sector impartiality

Across the world, the public sector tends to be a fairly professional affair. A job in the public sector generally emphasises rationality and analysis and idealises the careful, logical and dispassionate consideration of different options. As public servants, we are expected to be objective and non-partisan. Such tenets are core values for public servants – fundamental beliefs of the public service. Public servants are expected to hold societal aims above their individual concerns.

Such established core values help bind the public service together as an institution. They help to inform what should be done, and how. They provide a baseline for expectations of what to expect in interactions from across the public sector.

“Without feelings insignificant decisions become excruciating attempts to compare endless arrays of inconsequential things. It’s just easier to handle those with emotions.” Ann Leckie [1].

“It’s easy to make decisions, once you know what your values are.” Walt Disney [2].

Yet decision-making is not and should not be a completely dispassionate matter. After all, the motto of the OECD is “better policies for better lives”, not “better policies for better technocracy.” The work of the public sector must be informed by emotion and other values if it is to make a positive difference to the lives of those it serves. Decision-making needs to be about what matters, and ultimately that is a question of other core values: what do we believe to be important?

For different public sector organisations with different functions these core values might be a matter of welfare, of health, of environmental stewardship, of economic growth or the rule of law. These values in turn are shaped by broader societal values, as expressed through the political process.

In short, core values are an important ingredient to the work of the public sector. What we as public servants believe is important matters (because it shapes how we work), and what is held dear by society matters (because it shapes what the work of the public sector is for).

What we value, or what those values look like, can change over time

It is important to understand and be aware of core values then. In order to be effective, the public service needs to recognise the value sets that it may be interacting with, or it will lose the trust and confidence of citizens that it is working for the right aims.

Yet it is not always easy to identify, in a fast-changing world, what it is that we believe to be fundamentally important. After all, as our reality changes, what we want and what we believe is important may also change.

For instance, as new technologies (biotechnology, digital technology, 3D printing) provide us with greater insight into our world, new things become possible. These possibilities (e.g. genetic manipulation, automation, or 3D printed firearms) can affect our existing values, thereby forcing (re)consideration of what matters.

If we take social media as an example, it has changed what we know is possible about how citizens and governments can interact. In turn, it has shaped what people believe about how government should interact, and thus what they expect and value from government. “The possible” affects our expectations, and our expectations shape what we believe is important, and thus what we value.

An added nuance to this is to recognise that sometimes the manifestation of a core value may change, but the fundamental belief underpinning it will stay the same. To take an example, our current value systems tend to place a lot of emphasis on people’s economic contribution through employment. We believe work is important, as both a function and as a part of individual identity. Yet, future automation may challenge notions about the importance of work and what (economic) role humans should play. In a world of automated labour, the core value about work may become untenable or redundant. However, the underlying belief in the value of people may stay the same – rather its presentation may shift.

Nonetheless, as a general observation, we can say that innovation shapes what is possible, and, in turn, these possibilities can affect our values.

If it is important for the public sector to be aware of core values in order to inform decision-making, then it is also important for the public sector to appreciate how core values may change due to innovation.

Differing innovation facets are likely to relate to values in different ways

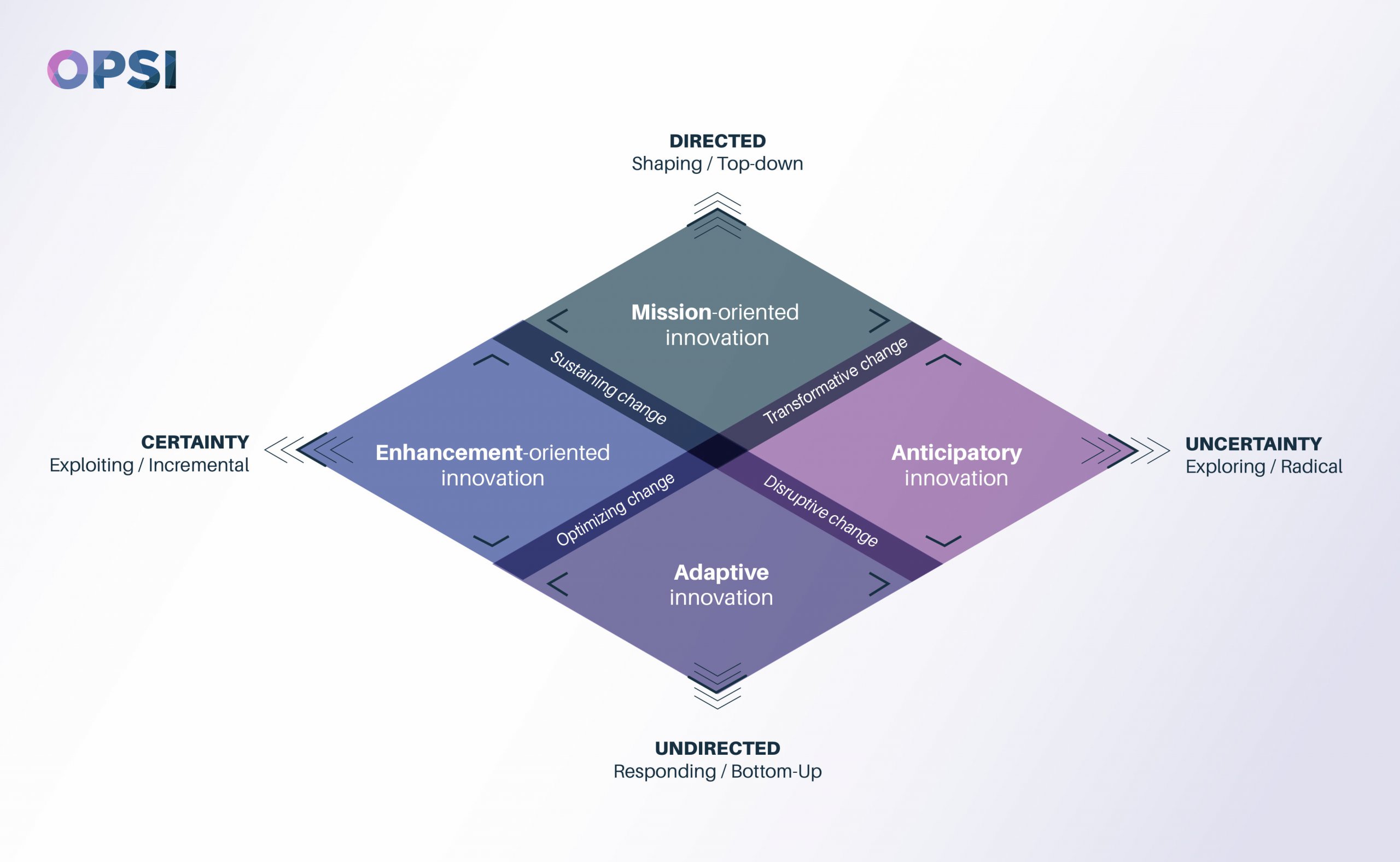

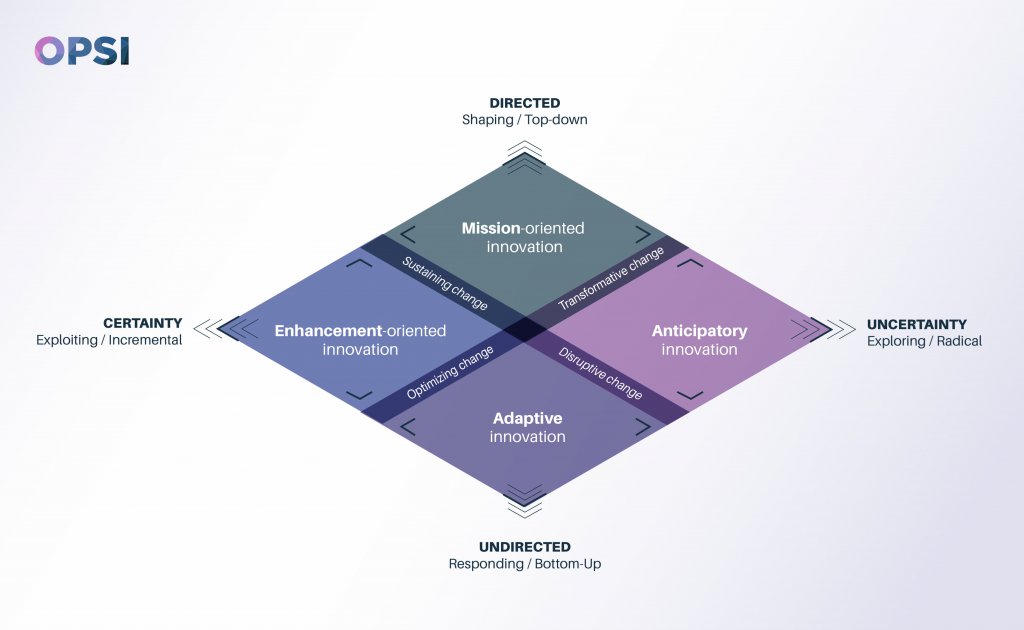

How does any of this this relate to our innovation facets model?

Well, we propose that we can use the facets model to think about how different forms of innovation may interact with existing value sets. We hope to help show that the facets model can be used to gain insight into the value changes that different innovations may bring, and the counter-reactions that may also occur.

To quickly recap the differing natures of activity in each facet:

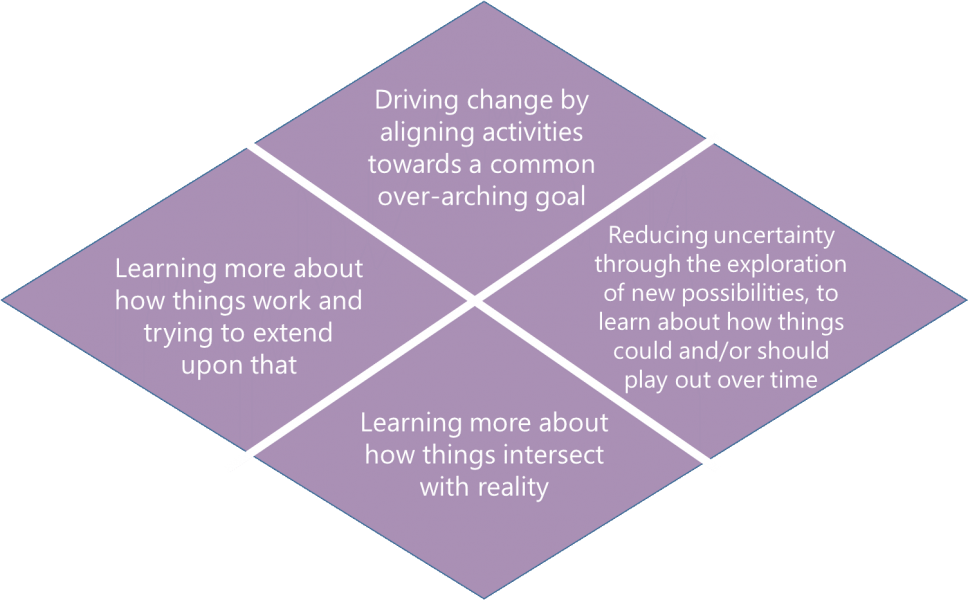

- Enhancement-oriented innovation: activity in this facet is about learning more about how things work and trying to extend upon that. Greater learning about what works enables interventions that are more efficient and/or effective.

- Mission-oriented innovation: activity in this facet is about aligning activities towards a common over-arching goal. By creating a big and audacious purpose, it can activate the interest, engagement and investment of others towards achieving an important goal.

- Adaptive innovation: activity in this facet is about learning how things function in reality, what is changing on the ground and what that might imply, and exploring the opportunities that might come from that.

- Anticipatory innovation: in this facet, activity is about reducing uncertainty through the exploration of radically new or different possibilities, to learn about how things could and/or should play out over time. As more is learnt, the different possibilities and pathways, and their implications, become clearer.

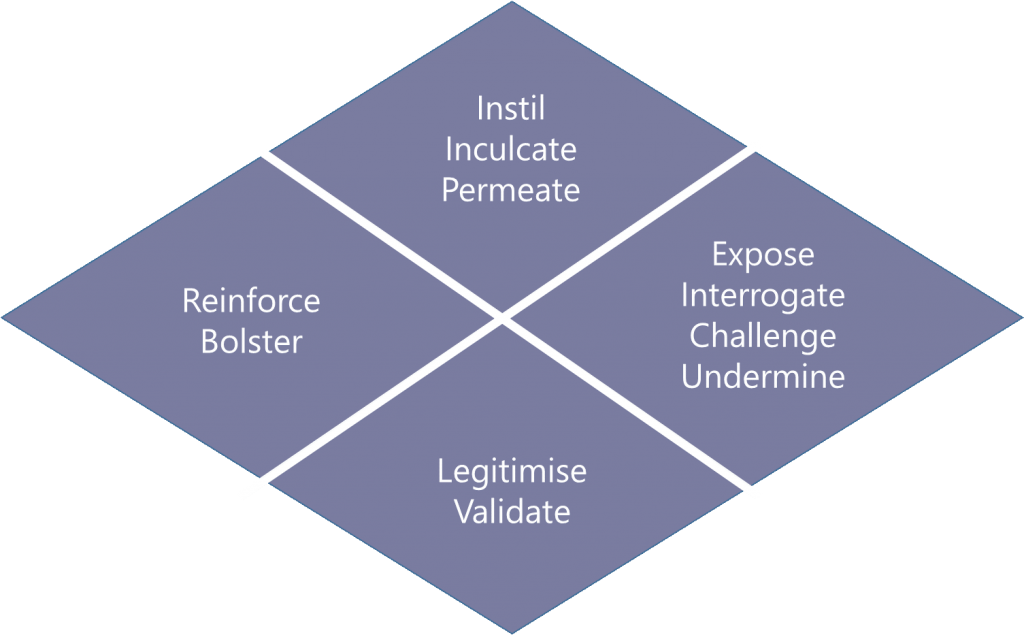

We can then consider how each of these activities may intersect with the core value sets that might exist.

- Enhancement-oriented innovation: if activity in this facet is about learning more about what works and extending upon that, then activity within this facet will tend to reinforce or bolster existing value sets. For instance, if there is a behavioural insights innovation that helps increase the compliance rates for on-time payment of taxes, then it is likely that this will reinforce existing values about the necessity of compliance and prompt payment (and perhaps any underlying value sets around the legitimacy of government taxation, the role of the state and efficiency).

- Mission-oriented innovation: if activity in this facet is about driving change, then such activity will tend to instil, inculcate or permeate a desired set of values. For instance, if we take the example of a country transforming their energy system to renewable energy in a fight against climate change, then this is likely to push or encourage particular societal values around the role of the government and structural adjustment. This in turn will shape beliefs about the economy, and affect core values about the type of work that is important – e.g. away from coal and carbon-intensive sources, and shape the associated expectations about their role in the country and its economy.

- Adaptive innovation: If the activity in this facet is about learning more about how things interact and intersect with other existing activities, then it is likely that it will tend to legitimise or validate emerging values. For instance, if we take the example of when government agencies first started experimenting with social media in response to shifting citizen expectations about how communication should happen, the use of social media by government sent a message that this was okay. While it may not have been as official as other channels, in many countries it soon became the norm for government to engage with citizens on social media, despite it being sometimes very different from other, more bureaucratic communication methods.

- Anticipatory innovation: if the activity in this facet is about reducing uncertainty through the exploration of radically new or different possibilities, then such activity will often tend to expose, interrogate, challenge, and undermine existing values. By putting up everything for question, innovation here can fundamentally expose our existing values, interrogate what it is we actually value, challenge whether that is the right thing, and undermine our beliefs as to what the right thing is. For instance, if we again take the example of automation, anticipatory innovation work that hints at or explores a jobless future may be quite daunting and challenging for our core values about who we are, what we do (or are ‘meant’ to do), how wealth is generated and distributed, and how we relate to other people.

This is not to say that any of this is the prime intent of activity within a facet. Rather, it is to suggest that this will be a natural tendency or result of innovation within a facet. This thinking helps us to consider (and possibly foresee) how different types of innovation may be received in different ways and to prepare ourselves to respond. From our description here, it suggests that one of the difficulties that will accompany anticipatory innovation is that it will often be uncomfortable. Challenging core values is challenging a part of the self, as well as group or social identity.

For every action, a reaction

“Fear of loss can lead individuals or groups to avoid change brought by innovation even if it means forgoing gains. But much of the concern is driven by perceptions of loss, not necessarily by concrete evidence of loss. The fear or perception of loss may take material forms, but it also includes intellectual and psychological factors such as challenges to established worldviews or identity.” Calestous Juma [3]

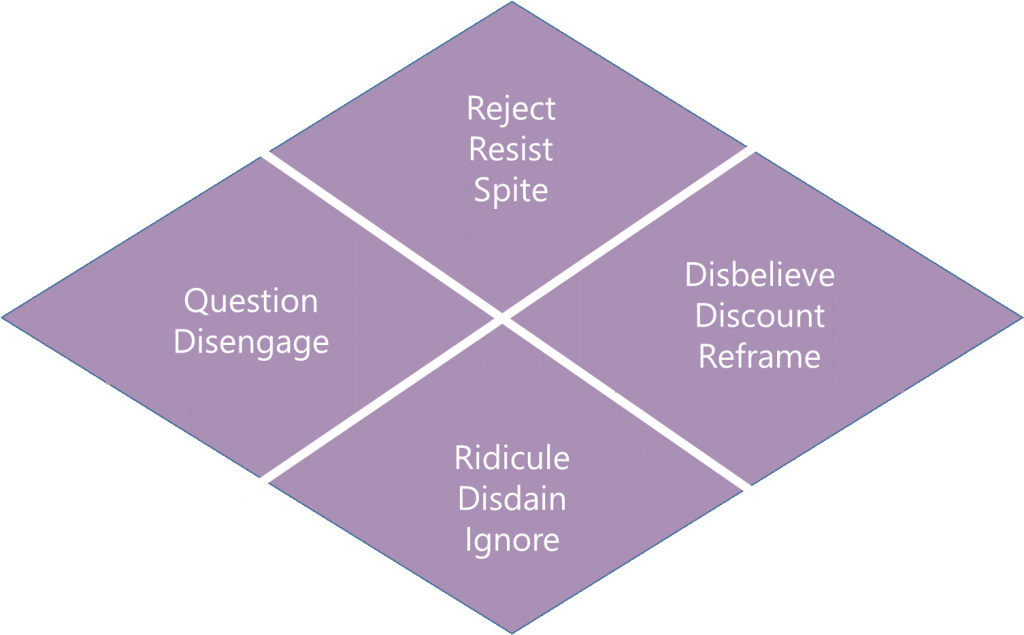

Yet the discomfort that can come with innovation can also spur reactions and counter-reactions to innovation. When core values are challenged, sometimes the natural response will be to push-back, to resist, to reject, to ridicule, or to refuse the changes that underlie the challenge.

To explore this further, we can think about how people might respond to activity in the different facets. While there may be positive responses, these are generally easier to manage or deal with (though there can be difficulties with too much success). Therefore, here we will focus on more ‘negative’ or contrary responses that may cause complications for any public sector leader or steward seeking to manage a change process (whether externally generated or coming from government).

There may not always be such reactions of course, but it can be helpful to consider where and how push-back to innovation may manifest. Equally, it is important to remember that such resistance may well be justified. An innovation may seem better in theory, or from a particular perspective, than in reality, as it may actually have some significant negative impacts upon others.

How then, might push-back likely manifest itself when viewed through the lens of the four facets?

Enhancement-oriented innovation

“You may have a new idea, but it stems from input somebody gave you, and that could be wrong or your senses could have been lying to you.” C.J. Cherryh [4]

If we accept that activity in this facet is likely to bolster or reinforce existing values, then we can imagine that some may question or disengage with it since it is not relevant to them. Enhancement-oriented innovation, by building upon “what is,” may neglect those who are currently not benefiting or who have unmet needs. To take our earlier example of a behavioural insights innovation, which helps boost compliance of on-time payment of taxes, we can imagine someone who has extremely complex tax affairs because of a complicated welfare system, or someone who has had an adverse experience with the tax administration. In such cases, there may not be a belief that the tax system delivers social value, and thus scepticism about anything that attempts to make a bad system work better. Enhancement-oriented innovation is less likely to garner a significant reaction than other forms of innovation, as it is not fundamentally challenging the status quo, rather it is doubling down on what already is.

Mission-oriented innovation

“The quickest way to find out who your enemies are is to try doing something new.” Calestous Juma [5]

If we accept that driving change is likely to instil, inculcate or permeate a desired set of values, then we can imagine that some might reject, resist or act in spite of the mission. Mission-oriented innovation, by projecting a desired state of affairs, may antagonise or mobilise those who believe differently. This alternate view of how the world “should be” might even be catalysed by the creation of a mission, by creating something that can be reacted to. To take our earlier example of a country transforming their energy system to renewable energy in the fight against climate change, we can imagine some people who may take this as an attack on how things were done previously, and therefore an attack on the beliefs and values that accompanied those past practices. A mission can also be interpreted as a de-prioritisation of other agendas, as everything else is seen as secondary to the mission being pursued, and thus an implicit rejection or discounting of those other causes. In such cases, the mission may be seen as a provocation to fight against, or something to hinder, delay or obstruct for as long as possible, in order to extract as much as possible from the existing state of affairs.

Adaptive innovation

“Bureaucracy destroys initiative. There is little that bureaucrats hate more than innovation, especially innovation that produces better results than the old routines. Improvements always make those at the top of the heap look inept. Who enjoys appearing inept?” Frank Herbert [6]

If we accept that adaptive innovation will likely act to legitimise or validate emerging values, then we can imagine that some might ridicule, disdain, or ignore the innovations and the associated emerging values as an affront to existing practices and the associated values. Adaptive innovation, by validating the insights of practitioners and stakeholders, may upset those who are expert or who have positional authority. To take our earlier example of government agencies experimenting with social media in response to shifting citizen expectations about how communication should happen, we can imagine that some leaders and professionals within the public service found the new channels and the new ways of interacting quite confronting, puzzling or confusing. In which case, we can also imagine the response to be one of ridicule, disdain or of ignoring the new practices as a way of maintaining authority or because there is no capacity to constructively engage with the shift.

Anticipatory innovation

Cassandra (also called Alexandra) is the Trojan seeress who uttered true prophecies, but lacking the power of persuasion, was never believed. [7]

If we accept that reducing uncertainty is likely to expose, interrogate, challenge, and undermine existing values, then we can imagine that some might disbelieve, discount or reframe the anticipatory innovation. Anticipatory innovation, by questioning the status quo, can shake what was previously stable. To take our earlier example of anticipatory innovation exploring a highly automated future, we can imagine some who might respond that such a future is too unlikely, as previous technological change has created more jobs than it has displaced. Or that such a future will never happen because the previous developments of the (exponentially changing) technology mean that it will never be advanced enough to allow that degree of automation. Or that even if it does occur, it will not matter because capitalism/humans/society is adaptable. Even though the future is unpredictable, we may often respond by predicting scenarios that mean we do not have to change our existing values.

If we can understand how different forms of innovation may spark different reactions and counter-reactions, then we can be better prepared for them, even if it may not be possible (or desirable) to avoid them. Perhaps most importantly for innovation practitioners is the illustration of how an innovation, no matter its potential, can be met by push-back. When you do something that potentially upsets people’s core values, it is important to be prepared. Equally, an absence of a reaction may also be telling (e.g. apathy, disengagement, an indication that the innovation is very much needed, or an indication that the innovation is not that innovative).

This is all new, so let us know what you think

This thinking is based on our team’s experiences, what we have witnessed in different country contexts, and some of what we have drawn from differing public sector innovation examples. However, some of this is still speculative and it needs more rigorous testing. Part of that will be through our work with practitioners in different countries, but an equally important part is to learn from the hivemind, and to hear from you about whether this makes sense and whether you have any examples that support or contradict it. If you have any feedback, we really value comments, or you may wish to share your thoughts with us by email or on Twitter.

[1] Anne Leckie, Ancillary Justice, 2013.

[2] https://www.brandingstrategyinsider.com/2008/01/great-moments-3.html

[3] Calestous Juma, Innovation and its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies, 2016.

[4] C.J. Cherryh, Cyteen, 1988.

[5] Calestous Juma, Innovation and its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies, 2016.

[6] Frank Herbert, Heretics of Dune, 1984.

[7] Carlos Parada, http://www.maicar.com/GML/Cassandra.html