Innovation facets part 4: Mission-oriented innovation

In the last post in our innovation facets series, we looked at the particulars of enhancement-oriented innovation. In this post, we examine in detail the mission-oriented innovation facet – what it is, what role it plays, how to support it, and the key considerations.

This post is us at OPSI “showing our work”, as this is still very much thinking that is evolving. Your feedback will help us in distilling the key messages, to ensure practical guidance for public servants everywhere.

Mission: “An important assignment given to a person or group of people | a strongly felt aim, ambition, or calling”[1]

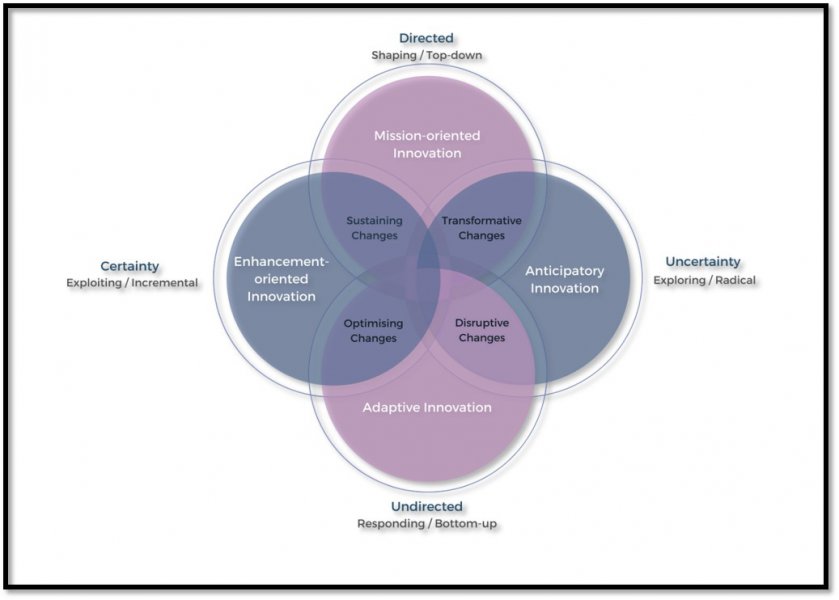

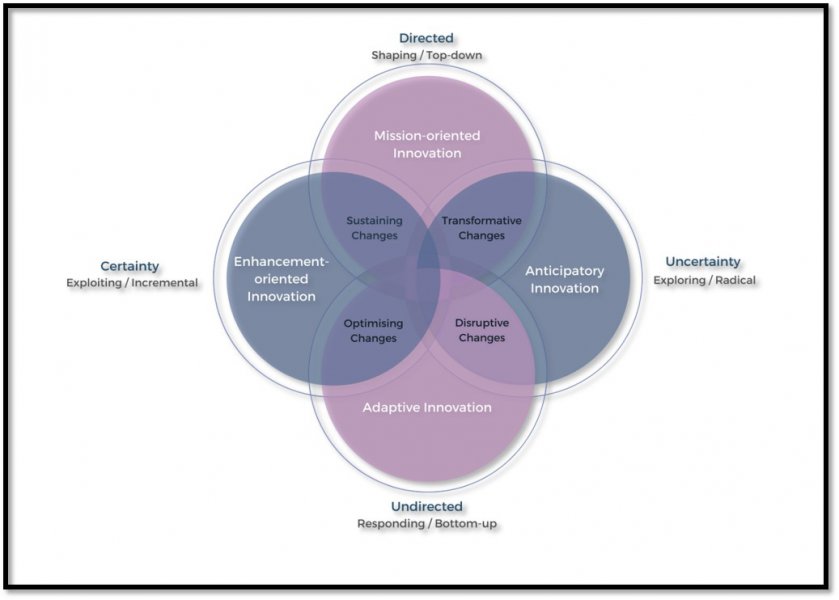

As we noted in the first post in the series, mission-oriented innovation:

- is where there is a clear outcome or overarching objective for which innovation is harnessed. There is a clear direction, even if the specifics of how it will be achieved may be uncertain

- can range from the incremental to the more radical, but may often fit within, rather than subverting, existing paradigms

- is exemplified by the mission of going to the moon. There was a clear objective, determined from the most senior levels, meaning that there was an overarching driving force that guided the relevant ecosystem players as they worked together to achieve the goal, and to drive new learning and knowledge in order to get there. This top level objective can provide the cover (and resources) for all sorts of experimentation, it spurs on very different kinds of innovations, but there is a clear sense of what needs to be achieved, even if the means by how to get there is not determined or made explicit

- can be very important for achieving societal goals, though it also works at an organisational or individual level to align activities. Public sector bureaucracies are naturally attuned to this sort of innovation, provided there is sufficient political will.

My colleague Piret Tõnurist gives a quick overview of mission-oriented innovation:

What does mission-oriented innovation involve?

Mission-oriented innovation starts with a driving ambition to achieve an articulated goal, though the specifics of how it might be done are still unclear or are not set in stone. It is about asking “How might we achieve X?”, with X ranging from the world-changing (going to the moon) to the significant but relatively contained (ensuring better services). It can be something that spans multiple organisations and involve the whole of government, it can be a single part of an organisation, or it might even come from outside of government (e.g. Alphabet’s X-Company with its mission of “We create radical new technologies to solve some of the world’s hardest problems”). Wherever it comes from, it revolves around a public or collective-oriented mission that is significant and encompassing enough to be meaningful and resonant to actors outside of the usual audience.

At a working level, it is about trying to drive change by aligning activities towards a common over-arching goal. Methods and practices that can underpin mission-oriented innovation include the use of systems thinking, strategic design, open innovation, and challenges and prizes. Of course not all of the changes that occur under a mission may be innovative; sometimes well understood interventions may make the largest contribution. Yet, by making explicit an ambitious goal, and thus one that implies a significant departure from the status quo, some innovation is likely to be necessary to achieve the desired outcomes.

Some examples of mission-oriented innovation include:

- the “Energiewende” (energy transition) in Germany, which seeks to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to vastly scale up the contribution that renewable energy makes to the electricity grid

- the ambition of dramatically reducing drug and alcohol use and abuse among the teenage youth of Iceland

- India’s energy strategy, which seeks to more than triple the installed capacity for renewable energy by 2022

- the “small business fix-it-squads” of Australia’s Taxation Office, bringing together small business owners, tax professionals, federal, state and local government agencies and intermediaries to examine problems affecting small business owners. By having a clear goal (improving the business experience of government), new solutions become imaginable.

A mission can then be something global and transformational, or it can relate to a particular function. The unifying quality is that the mission is significant, specific and meaningful enough to drive change.

What to watch out for with mission-oriented innovation?

Mission-oriented innovation is, in some ways, something that is natural for government; after all, it is about working towards a goal on behalf of collective interests. Where there is the political will, the public sector can move mountains.

Despite this, there are some potential issues in pursuing mission-oriented innovation that should be considered.

- Ramifications and unintended consequences. A clearly framed mission can make certain changes seem logical or essential, thereby helping push forward innovative activity. However, sometimes the ramifications of those changes will not be given much consideration, as they are not as important as the goal to be achieved. Nonetheless, these ramifications or unintended consequences may end up damaging the viability of the mission.

- Neglect of other issues. A focus on a mission can mean that other issues are naturally deprioritised. This can mean that other parts of the organisation or relevant ecosystem that are not linked to the mission can become resentful of the mission, seeing it as distracting from their work and objectives, which they naturally feel is also important.

- Activating resistance. A clear mission can act as a target, and draw together those who are against the changes. While a mission may seem a clear good, there will always be vested interests that may be discomfited by a mission that seeks to change the status quo, and who may seek to delegitimise or slow down the innovation. By giving it a tangible focus, a mission can potentially provide a clear point of resistance that a more distributed or decentralised approach may have avoided.

- Mission-creep. A mission, by its nature, can build momentum. If it is successful, or has garnered significant support, there can be a push to either maintain the mission beyond the initial goals, or for additional items to be added under the umbrella of the mission in hope of leveraging the success for other goals.

- Mission lock-in. Another aspect of momentum is that the mission can keep going even when it may no longer be appropriate, whether because the problem has been solved, or because the ecosystem around the mission is invested in a particular understanding of the problem, even though the world may have moved on. Mission lock-in can involve losing sight of the bigger picture, and instead seeing the mission as the picture.

How does mission-oriented innovation fit within a portfolio?

To be effective over the longer term, any organisation or system will require a portfolio approach in its investments and efforts. In an uncertain world, you cannot predict the type, scope or direction of change that you will be confronted with. Therefore governments need to invest in multiple strategies if they are to both avoid being blind-sided, and so that they have a range of choices available to them in how to respond.

So how does mission-oriented innovation fit within a portfolio approach?

The approach of mission-oriented innovation can have significant advantages, as it leverages the natural machinery of government to achieve a particular priority. An effective mission can drive significant transformation; changes that can ripple far beyond the initial mission aim. However, if there are multiple missions of similar scale being pushed at once, efforts are likely to be diluted or risk burn-out or disengagement from the relevant actors. Too many priorities can become the same as not having any, as everything seems equally important, and the sense of “mission” is lost.

If a mission is carefully scoped and tangible enough that relevant actors can see how it connects to them, then it can drive change beyond the incentives (e.g. subsidies or grants) that may be involved. Alternately, if the mission is framed in vague terms or as some all-encompassing motherhood vision, then it can lose its power as a driving force, as it may seem as too distant, too nebulous, or too generic to be a motivating platform for action.

Thus, an effective portfolio, whether at a whole-of-system level or at the level of an individual organisation, is likely to be one that has a few distinct missions, each supported or driven by different areas.

What are the likely preconditions needed for mission-oriented innovation?

We believe that in order for mission-oriented innovation to occur, there are several factors particular to this facet that need consideration or development:

- A meaningful mission. The mission, the goal or outcome sought, needs to have some degree of resonance and significance to those involved (or those that are hoped to be involved) if it is to have the effect of activating the energy and activity required. An ambitious agenda that expects or demands significant changes but is passionless or process-driven and technocratic is unlikely to drive the innovation required, unless the deficiencies of the status quo are particularly pressing and tangible (e.g. because of a crisis that necessitates change).

- A cultivated ecosystem. If the mission does not require or engage actors outside of the existing players, and thus continues to rely on the resources and perspectives that have already been at hand, then it is questionable why making it a mission will be any more successful than the status quo. Engagement with a wider ecosystem cannot come from nowhere however, and thus there needs to be consideration of whether other players will be willing and/or able to engage and participate in the mission.

- An ambitious goal. A goal that is seen as relatively achievable or reachable without much effort will not stretch the system sufficiently to drive engagement or openness to new ways of doing things or doing new things. If the goal is highly incremental in nature, then it is likely only incremental solutions will be considered (“We’re close, why jeopardise what’s working?”). On the other hand, if the goal is too ambitious then there is a risk that over time support will fade and other actors may disengage or reduce their participation as progress feels insufficient (“Why bother, this is impossible”).

How can mission-oriented innovation be supported?

What will not only allow mission-oriented innovation to happen, but will actively help it? We suggest that there are a number of things that can be done to support it, and that are particular to this innovation facet:

- Political commitment (or pressure). In order to be both believable and legitimate as a mobilising call to action, a mission-oriented approach to innovation requires explicit commitment and support (from the political and/or senior civil service levels). It should be noted that this commitment is distinct from leadership, in that a formal commitment can have mobilising power even without a leadership push, whereas leadership alone is unlikely to provide the incentive or activation necessary to mobilise actors, unless there is already high levels of trust.

- Tangible indicators or objectives. In order for the mission to be sustained, there will need to be a sense of progress, and that will require some measure that the activity can be evaluated against. The indicators or objectives will likely need to be either self-evident or be sufficiently meaningful to those involved, in order for actors to be able to assess their own contributions, as well as those of others.

- Questioning of existing activity. If those involved with the mission believe that what is required is just more of the same, then the potential for innovation is going to be significantly hampered. There has to be some degree of acceptance that the mission requires stretching beyond just doing more or doing better.

How to sustain mission-oriented innovation in the long-term?

Mission-oriented innovation can be somewhat self-sustaining if missions are successful and have social licence, so that they are seen as both necessary and appropriate. However, it is likely that sometimes this will not be the case and that the appetite for doing missions may wax and wane over time. Therefore, ongoing intervention is likely to be necessary to support a mission-oriented approach.

To sustain mission-oriented innovation as a practice/portfolio component it is valuable to consider:

- Investment (time, resources, attention) in the ecosystem, so that there are actors with the relevant capacities and capabilities that can be drawn upon if and when needed

- Established platforms, processes and protocols for enabling and undertaking missions, to ensure as sophisticated an approach as possible for scaling a mission and bringing in external parties

- Mechanisms by which to find an appropriate balance between shielding a mission from the pressure to deliver during the inevitable short-term implementation and learning curve, and avoiding mission lock-in that means a mission is stuck with even when it should not be.

What can derail mission-oriented innovation?

Each facet is vulnerable to being jeopardised in different ways. Mission-oriented innovation can be disrupted or derailed by:

- Introducing a lack of specificity, so that there is not sufficient sense of how the mission can be contributed to or what progress will look or feel like

- Granular detail about what is to be achieved, so that there is no room for rethinking how the mission could be achieved and so there is just more effort or investment put into the status quo

- A noticeable gap between ambition and action, so that actors observe or suspect a lack of sincerity and commitment, and become disengaged or cynical about the process

- A lack of respect or engagement for new or different voices, so that those outside of the existing set of actors do not feel their contribution is warranted or appreciated.

What are the signs that the innovation activity is transitioning to another facet?

In our innovation facets model, we note that innovation activity can, over time, move from one to another. Some signs that mission-oriented innovation activity is transitioning to the other facets include:

- Towards enhancement-oriented innovation: The focus on the overarching goal starts to shift, with attention moving to the process of what is being done, rather than the why. At an individual project level, this may be seen when there has been significant progress towards achieving the goal, and so the focus naturally moves more towards enhancing the interventions that have already arisen from the mission. At a portfolio project level, this might be seen when there is greater concern about consolidating progress rather than undertaking large-scale changes (e.g. because of a changing focus due to the relevant stage of the electoral or budgetary cycles).

- Towards adaptive innovation: Attention starts to move away from what is being aimed for, and to focus more on what works on the ground. At a project level, this may be seen when insights from the field indicate that perhaps the framing of the mission is not suited to the lived reality. At a portfolio level, this may occur when there is considerable disruption, and missions need to be reconsidered in light of a dramatically changed operating environment (e.g. after a major catastrophe).

- Towards anticipatory innovation: Interest moves from what should be, to what could be. Activity occurs more around exploring different alternative futures and what that might mean, rather than focussing on achieving a desired outcome. At a project level, this might occur when the mission is confronted with extreme uncertainty (e.g. the mission encounters significant unintended and unanticipated consequences because of new developments, requiring reflection on what is known). At a portfolio level, this might be seen where there is consensus that emerging weak signals indicate that new technologies may reshape what is appropriate (e.g. exponential rates of change in technology suggest that linear models of response will soon be overtaken by events).

An ongoing dialogue

The facets model has come out of our work with public servants from across different countries, and is a work in progress, with a number of hypotheses still to be fully tested.

Our aim is to help make practical sense of innovation for public servants, and so we value hearing from practitioners about their experiences and whether we’re hitting the right note. If you have any feedback, we welcome your comments, or you may wish to share your thoughts with us by email or on Twitter.

[1] Two of the definitions of mission https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/mission