Innovation is a many-splendoured thing

This post is authored by OPSI team members Alex Roberts and Piret Tõnurist.

We at the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation have discussions about public sector innovation every day. So, it can be surprising when we are asked, on a fairly regular basis, ‘what is innovation anyway?’ Of course it really should not be that much of a surprise. The word innovation gets thrown around a lot and is used to describe many things in many different ways. It is no wonder that people might be confused about the concept and want more clarity about what, exactly, this thing is.

This confusion is a problem if public sector innovation is going to become a more routine activity in governments looking to develop and deliver new solutions. Having a shared understanding of innovation matters. Without a collective sense of what it is, what it involves, and why it matters, it is going to be hard to get support for innovation. People need to understand what they are signing up for with innovation. Without some degree of consensus about what it is, there is going to be a misalignment of belief, intent, and action, which is likely to make the difficult task of introducing and applying novel approaches even more challenging.

So what is public sector innovation?

As a starting point to talking about innovation, we can say that it is the process of implementing novel approaches to achieve impact (in the private sector impact can be equated to competitive advantage, however in the public sector more complex values come into play). We can unpack this further, and say that innovation has three core dimensions:

- Novelty. Innovation involves introducing entirely new approaches or the application of existing approaches to new contexts

- Implementation. Innovation must be implemented in some form or have tangible influence; it cannot remain a theoretical idea, a policy on paper, or an invention that is never adopted

- Impact. Innovation must result in public outcomes – the change has to be realised in some form. Ideally these outcomes include efficiency, effectiveness, better outcomes and increased satisfaction (however innovation is not always a good thing and so it does not always result better outcomes).

If we then take a look at what that means in practice we can quickly start to see that the concept of innovation is not easy to pin down. For example, innovation is the realisation of:

- New products, services and processes

- New policies and systems

- New ways of thinking and of understanding the world

- New ways of acting and organising and relating to the world.

Innovation can also be about changes big and small. It can be about things that will probably work, as well as things that are ‘shots in the dark’, such as experiments with no certainty of success. And it can range from a pilot (an innovation applied in one specific context, perhaps only temporarily) to a whole-of-society intervention (an innovation applied across an entire nation).

Innovation, in short, is not one thing. It is a many-splendoured thing. It has many ‘facets’ or aspects, it can look very different, and it can involve very different things and have various aims. The confusion that arises around innovation is, we think, at least in part due to these many different qualities and characteristics of innovation. However, we think that if we can start to better describe and distinguish between the different facets of innovation, then it will be easier for people to engage with it, support it, and do it.

This blog starts a series of reflections on innovation and its varied nature. In this post, we explore the facets of innovation and why they matter to those trying to make change happen in the public sector. We suggest that governments need to not only be cognisant of these different facets, but also appreciate that each facet needs to be managed and engaged with in different ways. We then propose a model to prompt governments to think about why they are innovating and whether they are using the right mix of approaches to achieve those aims.

Innovation is varied

The first thing to note about innovation is its variance. Innovation might be about providing a biometric ID to your entire population and linking it to government service provision (the Aadhar initiative in India). It might be about developing a data embassy to safeguard the core elements of a digital state (Estonia’s world first data embassy). Or it might be about changing the frame of thinking for your welfare system from one of simple service provision to one of an investment approach (the Asker Welfare Lab in Norway). Or it might be several of these things at once. Public sector innovation involves many different processes, activities and ways of working, organising and relating.

If the forms that innovation can take are so varied, then it suggests that innovation might not be something that can be managed homogenously. If you have a completely new idea that challenges existing assumptions, power relations and behaviours, then it will involve different steps and challenges than those associated with adjusting something that already exists to make it work better for a slightly changed context. If you are trying to develop and introduce a radically new policy that reshapes the education system, then you are going to need to manage it differently to a process of undertaking small targeted experiments to improve the compliance rates for paying tax on time.

Innovation, then, is varied, and this variance needs to be managed through a range of different strategies and approaches. However, in order to be able to do this effectively one needs some way of appreciating the variance and what structures, resources and processes are best suited to which contexts.

Innovation has a purpose but not always a plan

Innovation involves changing the status quo, which is no easy feat. The difficulty inherent in innovation means that it rarely happens unless there is some sort of push or pull associated with it, for without political will or demand most changes are going to become bogged down in inertia. Therefore innovation is generally a purposeful act. If there is no purpose then it is unlikely that an innovation will get far, particularly in the public sector where existing structures, processes or vested interests are likely to besiege and begrudge it. A good idea without a client or a sponsor is just an idea.

Yet, this purpose is not always evident in the way that you might think. Sometimes the purpose is to allow for the unexpected to arise. It is about ‘play’ and having the space, freedom and slack to be able to think about how things could be done differently. Thus innovation can sometimes seem like a messy and undirected process, one of letting ‘a thousand flowers bloom’. When things are changing, no organisation or system can hope to direct innovation to account for all of the possibilities, so there has to be room for undirected, but still purposeful, innovation.

Of course sometimes the purpose will be very explicit and tangible. It might be about achieving an ambitious goal that requires the creation of new knowledge, new relationships, new structures and new activities. Such efforts – ranging from going to the moon to eradicating child poverty to the development of a new industry – are what Mariana Mazzuccato refers to as mission-oriented innovation. With such efforts there is a clear direction, i.e. there is a policy, an objective, or a rallying cry that provides a clear sense of not only what is intended but what is likely to be involved in getting there.

Both of these are valid purposes for innovation, yet, one has a clear direction and the other is intentionally directionless. Both approaches to innovation need to be recognised then, so that they can be valued and appreciated distinctly, and managed and supported in different ways.

Innovation comes with surprises both big and small

Innovation, being about doing something new to the context, is inherently uncertain. The novelty of innovation means that the outcomes cannot be guaranteed or fully expected, and unanticipated results will occur. Yet this uncertainty can range from the very high, where you have no idea or relevant precedent that can tell you what might happen (e.g. disruptive technologies that can upend existing paradigms and assumptions about how things work), to the relatively small, where you have a better chance of being able to assess and anticipate the potential impacts (e.g. such as when introducing a new service to a stakeholder group that is already well-known) or deal with them relatively quickly.

These differing levels of uncertainty have implications for the innovation process. When a government is faced with something where there is significant uncertainty a much more exploratory and tentative approach will be required, as the ramifications will need to be better understood before too much is invested or commitments are made. When there is less uncertainty, the approach can focus more on taking advantage of and exploiting the potential of the particular innovation.

Public sector innovation will occur in contexts with significantly different levels of uncertainty, and those different contexts will require different strategies.

Innovation requires a portfolio approach

So far we have seen that with innovation there can be:

- a purpose (e.g. discovery, making something work better, achieving a goal or responding and adapting to external changes)

- uncertainty (i.e. you don’t know what might work or be most appropriate or there is the potential for changes that will make existing strategies obsolete or untenable)

- a variety of possible different strategies and forms of innovation, involving different capabilities, competencies and resources (e.g. options including new policies, new technological responses, or new ways of interacting with citizens).

In such a setting, pursuing or relying on any one single option, whether innovative or not, is highly risky. To expect or hope that things go according to plan is to effectively gamble. Multiple options should thus be available, so as to offset the risk of any one option not working or to ensure that there is a viable option available should something unexpected occur that disrupts existing strategies.

For effective innovation, a portfolio approach is thus advisable. Different public organisations need different portfolios that encompass and allow for different types of innovation depending on their purpose. Without a portfolio, there is going to be a high chance of being caught unawares or not having a viable solution ready when circumstances change.

Public sector innovation is multi-faceted

We have now established that public sector bodies need to be able to:

- Manage different types of innovation in different ways

- Match different needs/issues to the most appropriate forms of innovation and connected skillsets and capabilities

- Engage with differing levels of uncertainty and structure their innovation efforts accordingly

- Oversee a portfolio of innovation efforts, one that provides enough options to ensure a result for diverging purposes for innovation, especially in situations when there may be significant uncertainty about what will work.

In short, governments should avoid treating innovation as just one thing, and should respect and appreciate different public sector innovation facets.

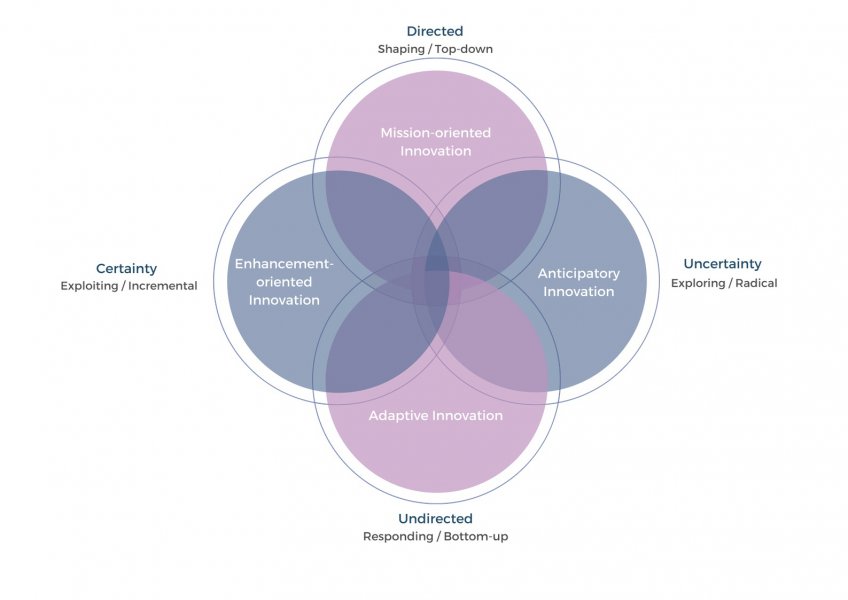

Out of our work with different government agencies and individual innovators from across the world, and building on the theory and practice of many others, we have attempted to identify those different facets. These facets are built upon two factors:

- Is the innovation directed? For example, does it have a clear intent/objective that it is trying to achieve, or is more about discovery and responding (proactively or reactively) to externally generated change?

- Is the innovation dealing with high uncertainty? For example, is the context one of exploring completely new ground, or is it one where things are relatively understood?

There are many other factors that can give insight into innovation, however, we think these are the most relevant if we want to aid individuals, agencies and governments in managing and maintaining a portfolio of innovation projects and associated capabilities that is diverse enough to meet a range of potential needs. We want to help government to prepare for the future as well as being able to use innovation to get better at what they are already doing. We want public sector bodies to be able to achieve their missions but also be capable of spurring bottom-up, curiosity-driven innovation that helps them adapt to a changing world.

The four facets of innovation

Using these two factors our framework identifies four public sector innovation facets that we think need to be considered.

- Enhancement-oriented innovation

- This focuses on upgrading practices, achieving efficiencies and better results, and building on existing structures, rather than challenging the status quo.

- It will generally exploit existing knowledge and seeks to exploit previous innovations. Innovation such as this can achieve greater efficiency, effectiveness and impact from existing processes and programmes.

- An example of such innovation could be the use of behavioural insights to improve the response or compliance rates for matters such as on-time payments. This innovation is not revolutionary or disruptive, and it does not involve rethinking the fundamentals of what’s being done, but it does involve a changed perspective and engaging with people in a different way.

- This is traditionally where most governments have focused their innovation efforts.

- Mission-oriented innovation

- This is where there is a clear outcome or overarching objective for which innovation is harnessed. There is a clear direction, even if the specifics of how it will be achieved may be uncertain.

- This type of innovation can range from the incremental to the more radical, but may often fit within, rather than subverting, existing paradigms.

- An example of such innovation is going to the moon. There was a clear objective, determined from the most senior levels, meaning that there was an overarching driving force that guided the relevant ecosystem players as they worked together to achieve the goal, and to drive new learning and knowledge in order to get there. This top level objective can provide the cover (and resources) for all sorts of experimentation, it spurs on very different kinds of innovations, but there is a clear sense of what needs to be achieved, even if the means by how to get there is not determined or made explicit.

- Such innovation can be very important for achieving societal goals, though it also works at an organisational or individual level to align activities. Public sector bureaucracies are naturally attuned to this sort of innovation, provided there is sufficient political will.

- Adaptive innovation

- For this facet the purpose to innovate may be the discovery process itself, driven by new knowledge or the changing environment. When the environment changes, perhaps because of the introduction of innovation by others (e.g. a new technology, business model, or new practices), it can be necessary to respond in kind with innovation that helps adapt to the change or put forward something just because it has become possible (i.e. entrepreneurial discovery).

- This type of innovation can also range from the incremental to the more radical. However the more radical adaptive innovation is, the more likely that a public sector organisation will either endorse it from a leadership level or seek to suppress it or force it outside of the organisation.

- An example of such innovation is how many government organisations have engaged with social media that initially started with bottom-up initiatives, and changed some of how they interact with citizens. Much of this innovation has been driven by people and organisations trying to react to a changed operating environment that meant that traditional channels sometimes were reduced in effectiveness, and citizen expectations about what was appropriate, needed and possible changed as social media introduced new ways of interacting. It can be driven by citizens themselves and only later on taken over or integrated into public policies.

- Adaptive innovation can be extremely valuable in matching external change to internal practices and usually it cannot be directed top down, because people’s developing needs cannot be prescribed. As such, adaptive innovation will generally be driven from the bottom-up, as those closest to citizens and services will often be the ones who see the need for change and react accordingly.

- Anticipatory innovation

- Here the key issue is exploration and engagement with emergent issues that might shape future priorities and future commitments.

- In contrast with mission-oriented innovation, this facet has the potential to subvert existing paradigms. Very new ideas generally do not cohabit well with existing reporting structures, processes, and workflows, as how the idea will work in practice still needs to be teased out. Anticipatory innovation therefore generally requires being sheltered from core business and having its own autonomy, as otherwise the pressures of very tangible existing priorities are likely to cannibalise any resources that are dedicated to something preliminary and uncertain that is without any guarantee of success.

- An example of this facet is where a government funds investigative work into artificial intelligence (AI) and its impact on service delivery. There is a high degree of uncertainty (What might be possible? How fast might that change as the technology evolves? How will people react to it?), and the exploration is unlikely to sit neatly with existing activity and operations.

- Anticipatory innovation is important because big changes are often easiest (and cheapest) to engage with and shape when they are still emergent and not locked-in.

The public sector needs to be multidextrous

Private sector innovation theory and practice often refers to the ‘ambidextrous organisation’. This is the idea of an organisation that can undertake discovery and the uncovering of new business opportunities (exploration) at the same time as doing execution and maximising existing business (exploitation). An ambidextrous organisation is one that can manage the tensions between doing what is needed now as well as laying the groundwork for the business of tomorrow.

Instead of being ambidextrous, we are suggesting that the public sector needs to be ‘multidextrous’, or able to successfully engage in and manage innovation across all of the four facets. It is unlikely that any one organisation will be able to be equally proficient across each of the facets, but through a mix of strategies and structures, we think that the public sector as a whole should be able to be.

A facet caveat

It should be noted that the ability to successfully utilise any of the different public sector innovation facets depends upon there being a degree of innovation “readiness” – an ability to engage with innovation in the first place. Innovation, and the associated strategies and capabilities that can produce it, are not things that can be turned on and off at the tap. Innovation will often depend on the existing knowledge, skills, systems and the learning that has occurred. For instance, an ambitious innovation mission that is a complete break from what has come before will likely fail if it does not involve considerable investment and development of ecosystem and organisational capabilities over an extended period of time. Adaptive innovation will only happen if there is the organisational slack available needed for experimentation and learning to occur as well as the ability to reorganise around new purposes. Innovation depends on the readiness, or the absorptive capacity, that has already been established. Part of our work programme, or our mission, at the Observatory is about exploring and articulating what that involves and working with countries to share their lessons about making it a reality.

Testing the facets – let us know what you think

Our end goal is to help governments build more sophisticated innovation portfolios that address the many-splendoured nature of innovation and to find the right ways to govern the variety of innovation tracks within these portfolios. While this work builds on the contributions of many others, this is still very much a work in progress. So before we dig further into the implications of thedifferent public sector innovation facets, we’re keen to hear what people think about this framework and whether it resonates.

What do you think? You can let us know in the comments here, or get in touch. We’re particularly interested to hear of any examples that people might have that would not fit within this framework.

In subsequent blogs, we will explore the intersection between the different facets, and go deeper into what each facet involves and what governing them in the public sector might look like. So, stay tuned for the next instalment!