Taking the Systems Work Forward: Workshop for Senior Slovenian Officials

In September, OPSI launched the report “System Approaches to Public Challenges: Working with Change” on dealing with complexity in public policy. To take this work forward, we launched a series of workshops with leading countries to discuss how systems approaches could change the everyday functioning of government. We held the first one on September 6, 2017 in Brdo pri Kranju in cooperation with the Prime Minister’s Office of the Government of Slovenia. This work was made possible thanks to Boris Koprivnikar (Minister of Public Administration, Slovenia) who recognised the transformative nature of OPSI’s recent work and spearheaded the process to create wider buy-in for these new approaches.

As such, OPSI gathered some “critical friends” of systems approaches to discuss the road forward and introduce these methodologies to the senior civil servants of Slovenia. From the international community, the session was joined by representatives from Finland, Scotland and the UK in addition to our old “systems friends” (Justin W. Cook, Dan Hill and Marco Steinberg) who helped us moderate the workshop.

Why did it take us so long to report on the workshop? We wanted to do it in a systematic manner: participants were surveyed afterwards on what they found useful and what they did not; some of our moderators were asked to write an account of the day and suggest improvements etc. Busy people as we all are, this takes time. Nevertheless, we have now all the perceptions together and we can give you a critical account of the launch of more hands-on systems work OPSI is trying to push forward.

Panel discussion

The day started with a high-level panel of senior leaders who have themselves attempted systems change. The general theme of discussion related to “tools of government” that have lost their relevance in light of the problems public sector faces today. Minister Boris Koprivnikar outlined how government is continuously called to be more like the big private sector digital giants, like Amazon in providing its services – “but nobody seems to ask, should we be like Amazon?” Minister Alenka Smerkolj argued that “It is not about things, it is about values and trust.” Sir John Elvidge proclaimed that he, as others in government today, should be “willing to accept any level of responsibility citizens put on government.” However, paradoxically, we live in an age of lowest trust in government ever. At the core, there is dissatisfaction with how and what government is doing, while, there is more access to policymakers then ever – in Sirpa Kekkonen’s words “the monopoly of providing knowledge and data to decision makers has been broken.” Thus, we live in the age of complexity, where even talking about problems and their causes become contradictory. This highlights the core dilemma in public sector today: it is not enough to change the modus of delivery of services (“Amazoniazation”), without changing the content of services themselves. This is about systems change. Paraphrasing one of our contributors: it is not only about verbs – e.g., how education is delivered –, but the nouns – what kind of ‘education’ is actually needed in the 21st Century.

In our experience, in more abstract discussion, consensus is easy to reach, but things become difficult when they are put in practise. How to take a project or program towards broader systems change? The panel agreed that the critical element is time, longevity of systemic change processes, but gave little on “how-to” carry out systemic change while many projects themselves were highlighted. To make it more concrete, we proceeded to the hands-on portion of the day.

What did we work on and what did we learn?

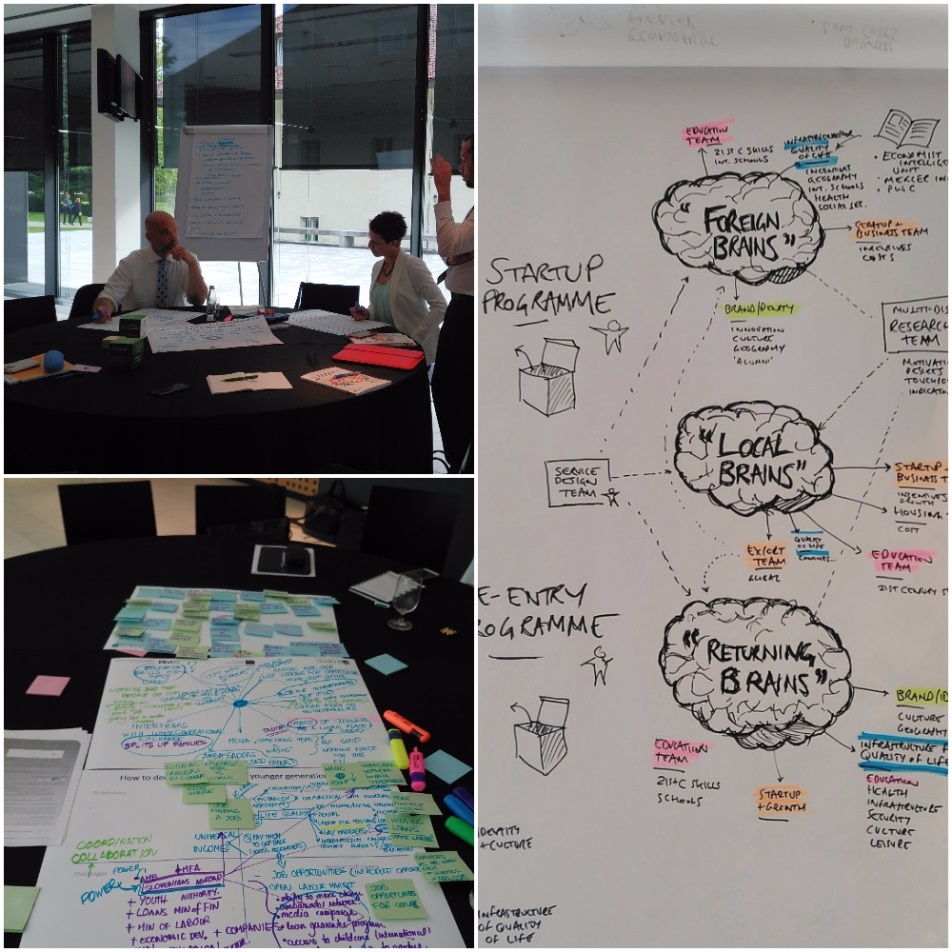

In cooperation with organisers from Slovenia, we agreed that real problems in the Slovenian context should be analysed. To identify these burning issues, we put together a “change group” of senior civil servants from Slovenia. Prior to the workshop in September, this group analysed and discussed a variety of problems the country is facing today. As we had such a short time to engage, we chose two problems very similar to each other – brain drain and faster/easier employment of skilled foreign citizens. The complex challenge Slovenia (like many other countries) is facing is that in a more and more open world citizens are leaving to global talent gravity centres, while it is difficult for foreigners to settle in the country. Thus, Slovenia may face a significant structural employment challenge in the future.

We had two hours to work in four groups. As groups were working in parallel on similar issues, we decided to also experiment a bit with facilitation. Namely, only the basic aims (reaching a project for systems change) were given to the moderators. The result showed clearly, that while similar things were discussed, the facilitation seemed to matter on how complexity was unpacked and which focus areas were selected. For example, one group went for the participant empowerment route, the other confronted taboos (fear of foreigners) as a vehicle to concentrate on real, critical issues in society, the third applied a moderator-design-led “brain circulation” model. In the following feedback from the group session, the methods and routes of discussion were debated.

However, in all groups the issue of “is mobility really bad?” raised its head. The emerging consensus was that it wasn’t; nevertheless, things become difficult when there is no incentive to return or there are barriers to it, for example, hurdles to integrating your foreign national spouse to the local society and labour market (the flip side of the complex problem). The participants went quite deep into the reasoning, life/career choices behind these developments which allowed them to look at the problem beyond their immediate silo and ask when and why should government get involved. Only after unpacking the problem, we started to debate on potential solutions and organisations needed to be included in the latter. Consequently, how complex problems are addressed, framed, really can lead to different solutions, and focus on different policies and policy actors. Here I will not go into the details of the solutions discussed. This session was explicitly conducted under Chatham House Rule.

All in all, the follow up survey showed that cutting across traditional organisational boundaries and working in a new way was deemed very useful.

Lessons learnt

While the workshop was a great success in our mind, there were several learnings from the process side that we would like to share with you and test out in our future engagement projects:

- The starting panel was designed to create high-level support for change; while the following group-work was supposed to allow the participants, in a low risk environment, to internalise new methods for working with change. But even then, participants need to have a basic level of understanding of systems/design techniques for the methods to be affective. A quick-pitch overviews of systems approached – tactics for systems change – were given to the participants, but the group works showed that these interventions proved to be too little: our moderators needed to work extra hard to make these concepts resonate. This is the major dilemma we are faced with when running these workshops: how to make systems approaches accessible (even agreeing upon the vocabulary) for novices in a day or a shorter period without simplifying issues too much.

- Consequently, we need also to design better interventions by increasing the time frame – two days instead of one, some socialisation in between – or giving some “homework” beforehand, not just reading, but maybe a mini-ethnographic exercise that will allow to go deeper in analysis during the workshop day.

- Additional helpful tool might be to introduce diversity in participants, so, civil servants and politicians are confronted with diverging mind-sets and views connected to the problem at hand.

- Also, more concentration around specific tactics of systems change may make it easier for system novices to participate in the workshop. This of course requires careful design.

- Most of all, a more in-depth piece of work is needed, so, that these quite insightful ideas emerging from the session could lead to a genuine shift in policy. Of course, the problems we analysed were a vehicle towards understanding new working methods, but after passionate and active engagement, it is right for participants to ask: what will happen next? We would argue that our work is simply a start, albeit a good start.

All in all, we tried to give the Government of Slovenia a ‘rapid assimilation process’ of systems approaches, learning-by-doing and allowing to ‘try on’ new ways of working in concentrated bursts. Did we entirely succeed? Probably not, but similar to this blog we are trying to teach how to embrace uncertainty and iteratively learn from each engagement.

Next steps

How are we taking this work forward? Our next workshop will be in Helsinki where we will concentrate on leadership issues. We have learned from our engagement with Slovenia and will switch it up a bit to experiment and push the envelope. For example, OPSI with colleagues from public employment group at the OECD are conducting some qualitative, semi-ethnographic research in Finland before the workshop. We will switch up the format slightly and work for two days with a slightly smaller group. OPSI will of course continue working with the Slovenian government as the forerunner in this area. For example, Slovenia has launched a new program for experimentation – “Thrill us with your problem” – which may require a new language around the effort in the public service. We are looking with interest how this works in practise.

What do you think about short-term workshops to create buy-in for systems approaches in governments? How to design them? How would you want to learn about systems approaches? Let us know, either by email or in our LinkedIn discussion group.