Designing a Public Sector Innovation Master Course

Public sector innovation is on the rise, in classrooms and outside. As a researcher, lecturer and ex- practitioner of public sector innovation, I was pleased to deliver an executive course on Innovation and Transformation in Government as part of Brazil`s National School of Public Administration (ENAP) Masters in Public Policy. In this blog, I will reflect my experience on the course design and delivery as well as on how OECD and OPSI tools have helped me to teach public sector innovation.

Once I received and accepted the offer, I started thinking about how to design my syllabus of 30 hours, delivered in nine lectures to remote learners via Zoom. At a Masters level, practice and engagement with the subject matter is key. As the next cohort of policy makers, I focused on an interactive delivery and group exercises to ensure theory meets practice, furnishing them with the right tools and knowledge to continue leading the way for public sector innovation. I decided to design a course of three main module blocks: (i) Introducing public sector innovation and innovation policy literature (ii) Managing Innovation Process: Merging theory with practice (iii) The systemic transformation through digital, social and responsible innovation.

Block 1: Introducing public sector innovation and innovation policy literature (10 hours)

The first block set the stage by introducing public sector innovation literature (click here for the comprehensive list). The content included definitions, innovation management models, diffusion of innovations theory, systems of innovation and innovation policy, which defines the different roles of government for managing innovation. The purpose was to clarify that innovation is more than technological change and that policy makers and implementers should distinguish individual, group, organisational, firm, industry and society level innovation development, implementation and measurement.

To situate this into practice, I designed three group-based activity: First, the hands-on analysis of the diffusion of the hydrogen fuel based technology helped students to understand that innovation policy should consider technical applicability, commercial viability and social risk perception together. Second, the students mapped the innovation eco-system in their country context – considering the actors, knowledge flows, financial flows and institutional settings – to better understand the system level dynamics. And third, as a summative assignment, they debated and discussed the extent of government intervention for economic growth via the science, technology and innovation policy.

Block 2: Managing innovation process: Merging theory with practice (10 hours)

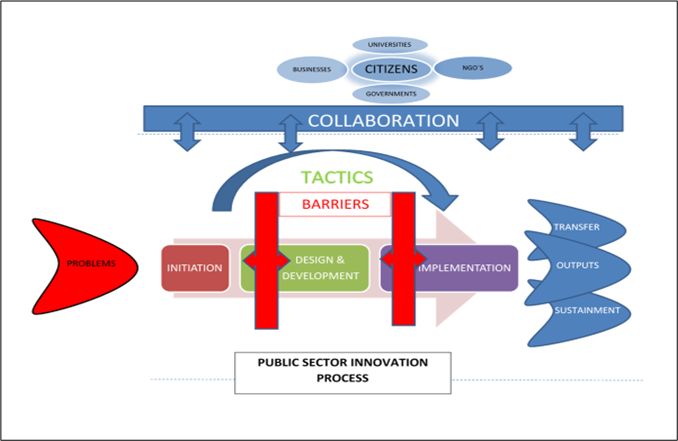

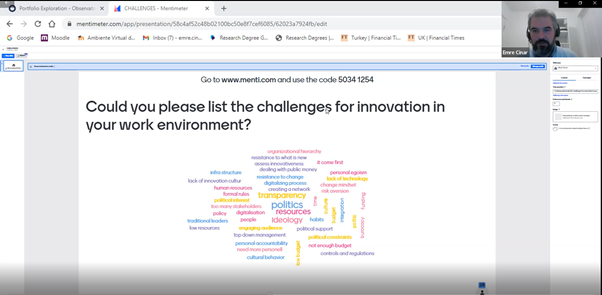

The second, and arguably most important, block aimed to discuss the complex nature and process of innovation and transformation within government. This helped students understand the innovation process (Figure 1) from the initial problem definition to the long-term sustainable solution which produces public value, followed by a discussion on how to manage this process as an innovator in government. Therein, I drew on historical examples of innovation in the public sector – including the notable examples of World Wide Web, GPS, police & military communication systems and open university – and distinguished unique characteristics of public sector innovation, such as the types, process models, drivers, barriers, collaboration and outcomes. The students reflected their experience on these concepts in their workplace through online collaborative tools (See Figure 2). This block was inspired by my academic research on public sector innovation and my contribution to the 7th edition of the “Innovation Management and New Product Development” textbook.

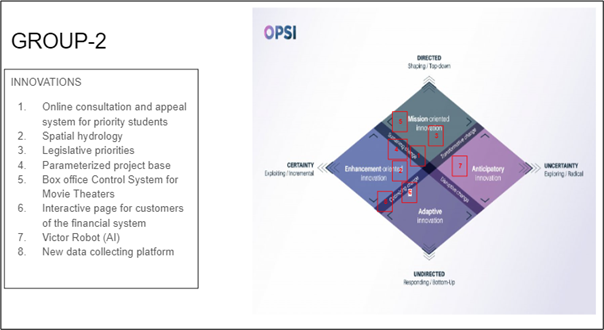

To elaborate on the multi-dimensional nature of innovation, I presented OPSI’s new innovation facets model, which identifies four types of complementary innovations in the public sector: Anticipatory, enhancement-oriented, adaptive and mission-oriented innovation. In addition to the Guide, I also used the thematic analysis of innovation facet briefs, which we developed for our research on OPSI cases from Canada and the UK with Professor Emeritus Sandford Borins. This was complimented by the OPSI Portfolio Exploration Tool exercise, a free self-assessment tool to help teams or organisations determine their public sector innovation portfolio. First, students individually in filled the online tool and discussed their results. Afterwards, students interactively mapped their most innovative workplace project. The exercise allowed students to engage deeply with the complex nature and various dimensions of public sector innovation, requiring them to think critically about where to place their innovation with respect to the four types of innovation. Furthermore, it allowed them to explore the whole groups’ innovation portfolio, and identify strengths and gaps where more innovation work needs to be conducted, most notably in the area of adaptive and anticipatory innovation (See Figure 3).

In addition, I drew in my own work on the role of the national context on public sector innovation. My comparative research started as an international study of UN Public Service Awards (UNPSA) applications from Italy, Japan, Türkiye, and, is currently being extended to studying UNPSA cases from Singapore, Thailand, South Korea and OPSI cases from Canada and United Kingdom. By calling attention to the various public management reform models and the role of the national context, students gained a stronger understanding of the need to consider the administrative, political, economic, technological, social and temporal context to develop and implement innovations in the public sector.

The second block culminated in a project submission to the OPSI Case Study Library. What better way to develop the skills of highly-ambitious and motivated public employees studying for a Masters in Public Policy than to engage with international organisations and showcase their knowledge? First, students analysed their selection of existing OPSI cases and identified the types, process dynamics and outcomes based on the learnings of the public sector innovation course. Subsequently, in groups, they co-developed an OPSI case application based on one of the workplace innovations identified earlier.

Block 3: The systemic transformation through digital, social and responsible innovation (10 hours)

The third block on digital transformation, social innovation and frugal innovation looked at the systemic transformation of government and society in tandem with Sustainable Development Goals and in partnership with non-governmental sectors. The final responsible innovation lecture proposed a cautious and ethics-oriented approach to innovation management. This block was inspired by my sustainability and diversity-oriented innovation management teachings at Portsmouth Business School as well as my practitioner experience of developing social innovations for women who are coming from rural areas and confronted by a lack of daytime places to socialise in city centres. The first group activity for the third block was to explore the OECD Digital Government and Artificial Intelligence toolkits to understand current country indicators and discussion how to improve them. The second activity was a critical discussion on the documentary, Period. End Of Sentence. The story of Arunachalam Muruganantham who invented a low-cost sanitary pad and frugal production tool in India attracted significant attention among the students. They were able to investigate the role of innovation in yielding systemic change via the empowerment of women groups who produced and diffused this innovation among their community.

The course closed with an online quiz on the presented subjects. All students achieved the course’s learning outcomes and five new OPSI cases were developed. The feedback for the course was excellent (average rating of 9.3/10), with strong appreciation for the OECD toolkit and Portfolio Exploration tool exercises.

This class was great, a lot of good examples for the public service, good opportunity to share with the classmates and to know more about their institutions and projects.

Course participant

I always believe that the best teaching environment is co-created with students and peers – that is the core of the learning. Many thanks to the Masters cohort for their engagement in public sector innovation and sharing of good examples. Special thanks to other co-creators of the course: Colleagues from ENAP, Professor Carlos Pio, Academic Director of the Masters Programme, Teresa Labrunie, Coordinator of the Programme, and Alice Pulliero, consultant in the course, for providing great feedback and support in the development and delivery of the course. Jamie Berryhill, Innovation Specialist at OPSI, shared information on the case acceptance process and guidelines. Professor Emeritus Sandford Borins provided suggestions and feedback on the course design and assignments.