How can government officials become innovators?

The case for innovation in the public sector is well known, but despite being on the agenda of governments for much of the past decade it often remains limited to small teams, scattered activities and/or high profile projects. Often these teams and projects involve external innovators and specialists being brought in to government to work on key projects. While governments will still need the expertise of external specialists – to ensure they maintain access to new, leading-edge practices and methods – it is crucial that existing officials become innovators themselves. Earlier this week (Tuesday 25th April 2017) the OECD’s Public Governance Committee and its Working Party on Public Employment and Management held a symposium on skills for a high performing civil service. To explore the issue of officials becoming innovators, one of the breakout sessions at the symposium covered the topic of skills and enablers for public sector innovation, considering questions around how to develop capacity and capabilities for innovation and what is needed of leaders to enable innovation?

Three key points emerged from the discussion in the breakout session:

- Many governments are facing the challenge of how to make innovation part of the mainstream.

- Openness is a crucial enabler. Always being open to new ideas and ways of working, being open to trying things out and learning from things that don’t work. And, being open to collaborating with others, both across existing silos and organisational boundaries within the public sector but also with new and different partners from beyond the public sector.

- We need to learn by doing – “learning” innovation is not like traditional civil service learning, it must be experiential, where officials learn innovation skills, knowledge and methods by working directly with those skills on real-world policy problems.

The Observatory’s work on the innovation lifecycle is documenting the tools and methods to deliver new projects and ways of working, however if officials do not have matching skills and capabilities then there will be limits to how far they can adopt innovative approaches. Therefore, as part of our grant from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research programme over the past year the OECD has been investigating the topic of skills for public sector innovation. The result of our work has been to produce a beta model of “core skills” for public sector innovation which we are sharing for comment. Our work on innovation skills also sits within the framework of the OECD’s skills for a 21st century Civil Service, and the beta model of core skills for public sector innovation will ultimately form an annex to this work programme’s final report.

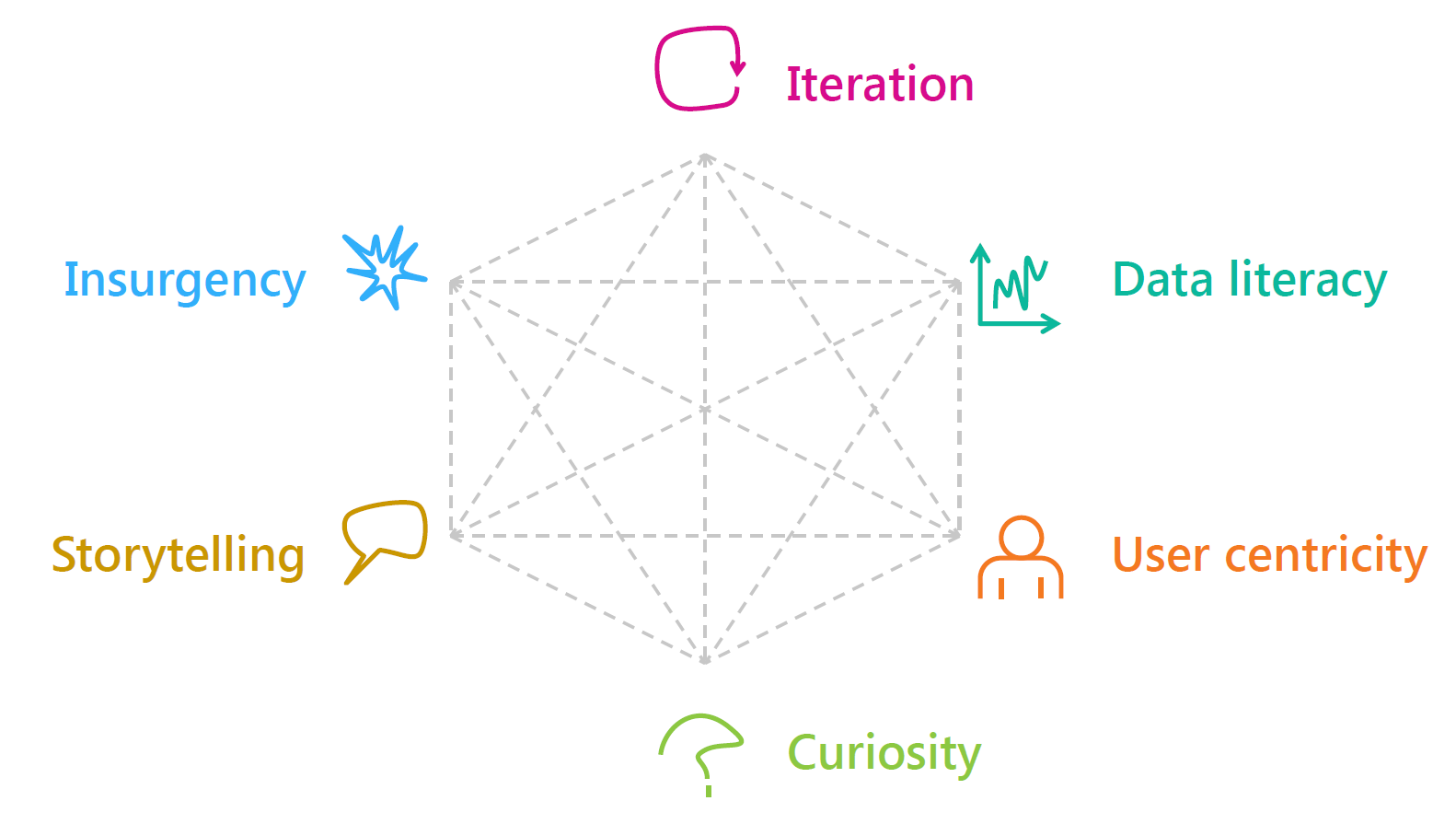

Our skills model is designed around six areas of “core skills”: iteration, data literacy, user centricity, curiosity, storytelling, and insurgency. These six skills areas are not the only skills for public sector innovation, each innovation project and challenge will have its own particular needs. Nor will all public servants need to make use of or apply these skills in every aspect of their day-to-day job. Rather, these are six skills areas that with proper promotion/advocacy and development we believe can enable a wider adoption of innovation practices and thus an increased level of innovation. In fact, there are a number of other skills that are already covered in existing public sector competency frameworks that are relevant for innovation, such as collaboration, strategic thinking, political awareness, coaching.

Iteration is about using incremental, and often rapid, approaches to develop a project, product or service. It can involve developing and refining prototypes, and conducting tests and experiments to identify the best solution. While closely associated with the digital agenda in government (such as the use of agile project management methods to develop digital services), there is wide applicability to policy-making in general: the behavioural insight revolution has raised the profile of policy experiments, and innovation labs have been promoting the use of design thinking and prototyping.

Data literacy isn’t about every civil servant becoming a data scientist or master programmer, although governments do need to recruit more people with specialist skills in collecting, managing, analysing and visualising data. Rather, it is that officials need to understand the importance of data, that decisions should be based on data so we can have data-driven public services analysing real-time trends rather than reacting to yesterday’s numbers. It is also about building better connections between those with and without specialist data skills: policy makers and service managers need to involve data specialists through the life of the project, while data specialists need to have the skills to communicate and interpret their results to a wide range of non-specialists.

User centricity is about thinking of citizen as “users” of public services that are trying to solve particular needs. These needs should be something that politicians and policy makers think up or assume, but should be needs that have been identified in research with real-world users. Officials shouldn’t just consider users at the start and end of a project, but involve them at different stages of a project – from sourcing ideas and co-designing approaches to testing and evaluating prototypes and systems.

Curiosity and creative thinking are about identifying new ideas and ways of working. It doesn’t have to be about coming up with something brand new that’s never been done before, it could simply mean seeking feedback or finding out how a different team or organisation delivers a similar goal/objective and identifying if their approach could be adapted into your own work. Or, when you are trying to solve a problem you can re-frame the situation to consider it from the perspectives of different actors/stakeholders.

Storytelling is about how we communicate in an ever changing world, where we no longer move from state A to state B but are constantly adapting. Using stories that can communicate the “journey” that connects the past and present to possible futures can make it easier for people to understand the rationale for changes and the direction that a project is taking. Integrating the stories of users, and how a project will improve their experience can help humanise changes and build support for your initiative. Stories are also important mechanisms for diffusing lessons, helping others to learn from your experience of what worked well, what didn’t go to plan and how things could have been different.

Insurgency is the lifeblood of public sector innovation, it’s about challenging the status quo and the usual way of doing things – “It’s always been done this way” isn’t an acceptable defence for poor quality or poor performance of public services. In exploring new and different approaches when something doesn’t go as planned we shouldn’t view that as a “failure” but as an experience that we can learn from to identify what does and doesn’t work. Innovation projects often involve working with different and unconventional partners – just because they are different from you doesn’t mean you shouldn’t work with them, they may have good insights and ideas that you would never have otherwise considered.

What about leadership and management of innovation projects/teams?

Over the course of the research to develop the skills model, no set of leadership and management capabilities have emerged that are particularly different from more “standard” concepts of leadership and management that are already espoused in public sector competency frameworks (openness, honesty, trust, strategic thinking, political awareness, staff development and capability building). In addition to traditional arguments about “transformational” and “transactional” leadership, it has been argued that leadership of public sector innovation needs to be “adaptive” and “pragmatic”. Thus, when leading or managing an innovation team there is no particular magic set “leadership for innovation” skills or competencies, rather what is needed is a stronger application of existing competencies alongside the adoption of the skills outlined in the model – because in doing something “innovative”, something that is different from the usual way of doing things, leaders, managers and their teams may encounter greater resistance or problems than initiating or leading a more “traditional” project.

Having identified these six skills areas the next challenge is putting these into practice within public institutions. A crucial factor here is to identify the enablers and barriers to making use of innovation skills and more generally to adopting innovative approaches in government. While the breakout session at the symposium provided some interesting insights into common issues facing the governments of OECD member countries in promoting public sector innovation. However, there is a limit to how effective general guidelines about enablers and barriers of innovation can be, it is important for individual teams and organisations to explore the enablers and barriers within their own context. To help with this, as part of the materials to support the skills model we have produced a workshop format that leaders, managers and others can use to explore how the six innovation skills areas can be adopted within organisations.

Putting innovation skills into practice?

Our next steps to our work on innovation skills and capabilities is to explore this issue of “putting innovation skills into practice” in more detail, in particular we want to use case studies to profile real-world examples of iteration, data literacy, user centricity, curiosity, storytelling, and insurgency in action.

Do you have a great example of one or more of these skills areas in action? Or have views on our model of skills for innovation? Get in touch and let us know, by email, via Twitter, or through our LinkedIn group.