How to make a public sector organisation a ‘Learning Organisation’?

Wales is in the midst of a major education reform process. As we know, good education policy is not about perfection on the page, it’s about what happens in the classroom. This is why Wales needed to think about not only effective policy development but also effective policy implementation.

What conditions make for effective policy implementation?

Our colleagues in the OECD Education Directorate’s Implementing Education Policy team collaborated with key actors in the Welsh education system to develop the ‘Schools as Learning Organisations’ model. In effect, the model’s seven dimensions focus attention on areas that support continuous learning, which, in turn, supports continuous change, allowing schools to carry out the requirements of education reform and continually provide quality education. The model’s seven dimensions are:

- Developing a shared vision centred on the learning of all learners.

- Creating and supporting continuous learning opportunities for all staff.

- Promoting team learning and collaboration among all staff.

- Establishing a culture of enquiry, innovation and exploration.

- Embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge for learning.

- Learning with and from the external environment and wider learning system.

- Modelling and growing learning leadership.

If resourced and supported well, activities across these dimensions will inflect the necessary dynamism and adaptability into schools so that they can continually understand and meet students’ needs, to best prepare for them the society in which they will work and live. Schools are currently engaging with the SLO model, with Tier 2 organisations (the local authorities work closely with the governing

bodies of educational institutions and the four regional consortia) currently looking to develop a mutual approach later this year. It is safe to say, they are on their path toward further development as Learning Organisations.

However, it was not enough that schools were developing as Learning Organisations. As the Welsh Education Directorate is responsible for setting the education reform agenda, this government department needed to ensure all tiers of the education sector are all joined up. They couldn’t just ‘talk the talk’ about change, it had to ‘walk the walk’ too. Therefore, the natural next step was for the Directorate to undertake the same assessment Learning Organisation model assessment, to see the extent to which it was already embodying the model’ and where it needed to improve to reflect its tenets better.

So, OPSI wanted to know, is the Welsh Government Education Directorate a Learning Organisation? Why (or why not)?

Yet, a public sector organisation is not like a school. Investigating the Directorate as a Learning Organisation needed to be different to the way our OECD colleagues in the Implementing Education Policy team investigated schools or worked with Tier 2 organisations. To do this, OPSI developed a mixed method (quantitative and qualitative), sequential explanatory research design. We knew what we were looking for (to see if the Directorate was a Learning Organisation) and what factors supported the presence of LO Model characteristics (or affected their absence).

Surveying public servants on the Learning Organisation model

OPSI adapted the Schools as Learning Organisations survey that was sent to schools to better fit a public sector context. Almost 60% of Directorate staff responded and respondents occupied a range of positions within the organisation.

The survey already included a variety of questions that teased out elements of each LO Model dimension, offering an array of characteristics that Directorate staff could say they saw in their organisation, by agreeing or disagreeing on a spectrum. The presence of these characteristics resulted in a composite score for each model dimension, showing the extent to which each dimension (and, thereby, the model) is already present.

In addition to asking staff questions about the characteristics associated with each LO Model dimension, the survey also included questions related to staff well-being, an important focus of the Directorate, and organisational outcomes. We were interested in whether staff thought they were on track to achieve their main policy aims in the short to medium term and how ready and robust the Directorate was, to deal with future changes. Using statistical analysis (an OLS regression), we were able to show that the LO Model dimensions, staff well-being and the capacity to achieve its missions were strongly associated.

The take-home message? Becoming a Learning Organisation makes good sense.

The survey generated useful quantitative data on all seven of the LO Model’s dimensions. The Directorate scored more highly on the dimensions ‘learning with and from its external environment and wider system’ and ‘promoting and supporting continuous learning and development for all staff’. This showed it was stronger in engaging external stakeholders and that professional development and learning was something that was generally valued. Having some hard data on all these LO Model dimensions, well-being and perceptions of mission achievement allowed us to start a conversation ‘organisational strengths and weaknesses’ with a degree of specificity, as each dimension’s score showed precisely where and by how much the Directorate had developed to embody certain characteristics they had deemed desirable and instrumental to its ongoing effective function.

Understanding the story behind becoming a Learning Organisation

In addition to quantitative specificity, we also wanted richness.

OPSI undertook qualitative interviews with Directorate staff, focusing on exploring what terms associated with the model meant (for example, when we use the words ‘collaboration’ or ‘team learning’, what do these terms mean to you?) as well as broader governance issues, major challenges faced when executing duties, and the nature of intra and inter-organisational collaboration.

These interviews were quite revealing.

The qualitative data showed us a multitude of factors influencing the Directorate fully embracing the Learning Organisation model, running the gamut from personal to political.

We heard about the impact of austerity measures and Brexit on people’s working lives as much as we heard about accessibility of professional development opportunities.

We heard about the relationships between teams and managers as much as we heard about the frustrations people faced when trying to use technology to connect across regions.

We heard about how co-design is celebrated and clustered in some areas (and absent in others) as much as we heard about challenges associated with staff promotion and retention.

It was a mixed bag.

At first glance, these reflections might seem too varied to say anything decisive or clear about the nature of the organisation.

However, the devil is in the detail.

Cumulatively, these anecdotes wove together to fabricate a bigger story about how the Directorate operates and the major challenges it faces not only when trying to undertake business-as-usual but also innovation. Qualitative data also gave us a deeper appreciation for how Directorate staff understood the term ‘learning’, what kind of learning took place at individual, team and organisational levels (and the challenges faced, at each) and what kind of structures, processes or attitudes help or hinder it. More importantly, it and how it was valued.

What is a ‘Learning Organisation’ for? Aligning ‘learning’ to strategic function

Now that we had a baseline for the extent to which the Directorate was already a Learning Organisation and a deeper understanding of the issues it faced on its journey to becoming one, we wanted to further breakdown the monolithic concept of ‘learning’. As our qualitative data showed, people conceptualised ‘learning’ in a variety of ways.

We needed to dig more into this.

As we know, there is no one kind of learning, but many. Each form of learning (be it personal, team or organisational) requires different forms of data or information development, collection, apprehension and use. There is different ways to learn and different ways to use learning to achieve different things.

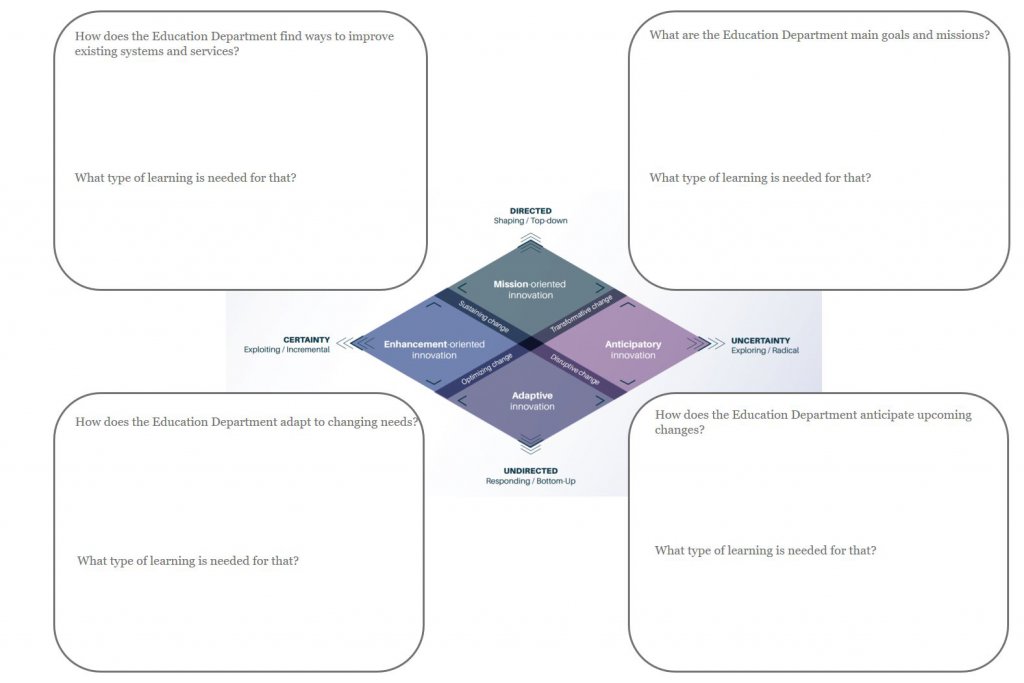

To map different forms of learning to different organisational functions, OPSI ran a workshop with all of the Directorate’s staff, where we posed the following questions:

- How does the Directorate find ways to improve existing systems and services? What type of learning is needed for that?

- How does the Directorate adapt to changing needs? What type of learning is needed for that?

- What are the Directorate’s main goals and missions? What type of learning is needed for that?

- How does the Directorate anticipate upcoming changes? What type of learning is needed for that?

Through this exercise, staff generated over 300 data points to detail ‘how’ they thought their organisation performed different strategic functions. This gave us an understanding of how people thought about the different categories of work that they do, be it making improvements, adapting to new needs, corralling resources and directing focus toward big policy missions or thinking about what the education governance needs of the future are.

They then generated over 200 data points regarding the ‘types of learning’ they associate with these functions. This part of the exercise helped us form a typology of the kinds of learning that occur (or staff believe should occur) so that these functions can be fulfilled.

While typologies are never perfectly delineated, the amount of overlap in staff’s answers when it came ascribing types of learning to organisational functions suggests an over-reliance on some types at the expense of other, possible ones. For example, it was popular to offer the kind of learning derived from stakeholder engagement of co-construction processes as a way of supporting different functions or activities. On the one hand, this shows strength and burgeoning maturity in a tricky area of engagement. Yet, on the other hand, ‘everything looks like a nail if you only have a hammer’. From this, we can see that this kind of exercise is useful in shaking out what the term ‘learning’ might mean, in different contexts, shining a light on strengths but also encouraging deeper consideration of what other kinds of learning capabilities need greater support, to better serve diverse organisational needs.

What would being a Learning Organisation allow you to do differently?

The organisational change this model aims to incite needs to be grounded in staff behaviour. A Learning Organisation should not be an abstraction but a lived experience.

So, if the Directorate is to ‘walk the walk’, then what does the ‘walking’ look and feel like? What would embracing the model’s seven dimensions allow staff to do (or do differently or better than before) to serve their various functions?

To start to ground the model in concrete behaviours and get a more nuanced sense of stakes and consequences, we included another activity to the workshop at the all staff Away Day. This activity required staff to imagine and ascribe behaviours to each of the model’s seven dimensions and to posit suggestions on how these behaviours could be instilled.

To begin, we asked everyone, if the Directorate supported team learning and collaboration; undertook continuous learning and development; shared a vision and goals; sustained a culture of innovation inquiry; collected and exchanged knowledge; learned with and from the external environment; and supported learning leadership…what would people do?

These questions generated over 400 data points on the different behaviours people could imagine flourishing if their organisation fully embraced all the model’s dimensions. Answers ranged from descriptions of what the working culture would feel like, attitudinal shifts, illustrations of possible, specific ways people or teams could interact with one another or personal attributes that people would display. Effectively, asking people to project their imaginations to a possible future wherein the LO Model is fully realised, put the difference between current and ideal behavior in stark relief. Answers showed that people wanted not just operational change, but personal (and inter-personal) change as well.

So, how do we get there? What possible steps could the Directorate need to take to start effecting the behavior changes people see as relevant to each LO model dimension?

To answer this question, staff engaged in a grassroots ‘solutioning’ exercise, suggesting different ways they could bring about the behaviours they had ascribed to each dimension. Over 300 data points were generated. From the suggestions we received, emergent themes included the need to:

- Improve the collection and sharing of information (and bolstering diverse capabilities to use it for different purposes)

- Extend and expanding the uses of collaboration/ co-design efforts (something that was already a burgeoning strength)

- Address the impact of hierarchy and silos

Addressing barriers to becoming a Learning Organisation

If these were the behaviours and changes people associated with each dimension and these were the steps people believed were necessary to getting there…then the question naturally follows, why aren’t these steps or actions being undertaken now? What is the missing link or the blockage? From looking at the behaviours people wanted to see in their organisation and the suggestions they made on how they could start to instill and sustain them, we could work backwards to determine the barriers to effective Learning Organisation model implementation. Using the collective wisdom of staff to find solutions to these barriers is the Directorate’s next step in the journey to realising the Learning Organisation model.

Getting clear on the ‘why’, not just the ‘what’ and ‘how’, for organisational change

A path to full Learning Organisation model realisation in the Directorate first required:

- A baseline of the extent to which it already is

- An understanding of how terminology and concepts associated with the Learning Organisation model were understood by staff and the broader governance challenges they face

- The behaviours people associated with each of the model’s dimensions and what enacting them would mean/ do for the good functioning of the Directorate

- Brainstorming possible ideas to What solutions people could think of to start to take meaningful steps to realising the model

Becoming a Learning Organisation is not an end in itself.

The Directorate embarked on this journey because there was a need to strengthen its capacity to develop and implement ambitious, wide reaching education reform in close cooperation with early work with Tier 2 Organisations and schools. The sequential, explanatory research OPSI undertook to assess the Directorate highlighted strengths and burgeoning maturity in some dimensions and opportunities for improvement in others. Beyond numerical scores for each model dimension, this research also explored what the broad term ‘learning’ meant in different context and broached a typology of ‘learnings’ as mapped to different organisational functions and as instantiated by various behaviours.

Through this, we got a real sense of the stakes; what it would mean for people and the quality of their daily work to operate or relate in ways that the model encourages.