From scattered to strategic: Iceland’s evolving innovation portfolio for international development – Part 2

This is the second post of a series on innovation portfolio management for international development organisation. In the first article we laid out our approach to designing tailored innovation portfolio management models and approaches for development funders. In this post, we share insights from our collaboration on innovation portfolio management with the Ministry for Foreign Affairs Iceland.

Iceland: A small but energetic player

For most development organisations and funders, innovation remains a sprawling collection of activities, often energetic, but largely uncoordinated. To a degree, this has also been the case for Iceland’s development co-operation. Iceland, a comparatively small but energetic player in the international development co-operation system, provided the equivalent of 0.28% (roughly 67 million Euro) of its 2021 gross national income towards Official Development Assistance. The primary goal of Iceland’s development co-operation policy 2019-2023 is to reduce poverty and hunger, while mainstreaming human rights, gender equality and sustainable development. Currently, Iceland invests about 20.7 million Euro in innovation for international development. As a small provider, Iceland leverages its comparative advantages in gender, geothermal energy, fisheries and land restoration. Iceland has been investing in diverse innovations across these areas, mainly to help spark and seed new solutions. For example, the country is financing exploration projects to adapt its innovative geothermal energy solutions to countries in Sub-Sahara Africa as well as providing financial and technical support for innovators to test and scale novel solutions.

Key considerations for Iceland’s investments in innovation for development

To further encourage and scale the development related innovations work of Iceland, the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the OECD embarked on an innovation portfolio management collaboration in 2022. The key questions that brought us together were: how can the scarce resources for development generally and for development innovation specifically be utilised in the most strategic and catalytic manners? At what stages of an innovation journey can a relatively small player like Iceland make the most difference?

The key takeaways presented below are based on insights gathered through a series of workshops and consultations held with over 50 development professionals and stakeholders, actively working on the implementation of Iceland’s development co-operation.

Step One: Identify strategic underpinnings for innovation investments

To steer the collaboration, we set up a core group of seven senior MFA colleagues and the working group for Icelandic non-governmental and civil society organisations in the field of development co-operation and humanitarian assistance. In order to identify the strategic purposes that matter most for Iceland’s development co-operation, we drew the following from the OECD criteria catalogue (see box below for details).

Assessing the nature of the innovation portfolio:

- Exploration vs optimisation: is the intent to optimise current delivery channels and solutions? Or is it to explore new ways of working, business models, development paradigms and/or delivery channels? This matters as we know that over-investing in the acceleration and optimisation of current ways of development co-operation will not result in the transformative changes required to reach the 2030 Agenda goals or advance societal and economic transformations in light of the climate crisis.

- Strong or nascent evidence-base: how well established is the evidence base of the development solution Iceland is supporting? What do we know about the effectiveness of each solution in different contexts? In other words: is the specific investment pursuing an approach that is largely untested or can we build on lessons from others?

- Degree and willingness to take on programmatic risk: does the solution pose a risk of failure to deliver? Programmatic risk refers to events or circumstances that could potentially improve or compromise the effectiveness of a programme.

- Degree and willingness to address stagnation risk: does the solution pose a risk of failure to evolve? The risk of stagnation refers to not engaging with fast-changing contexts or avoiding engagement with novel and poorly understood concepts, of only tackling issues where short-term results are guaranteed.

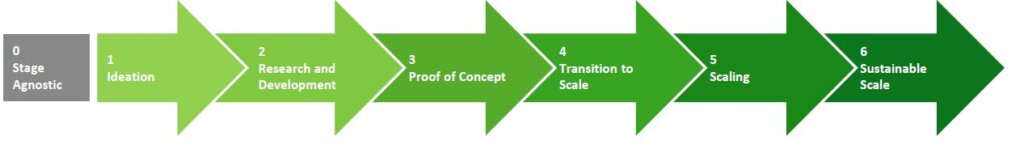

We mapped each programme and innovation in the portfolio along innovation scaling stages, from ideation to sustainable scale, using the International Development Innovation Alliance framework. Scaling stage is one of INDEF’s base criteria for portfolio management in development, along with funding volume and relation to specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Step Two: Map what is

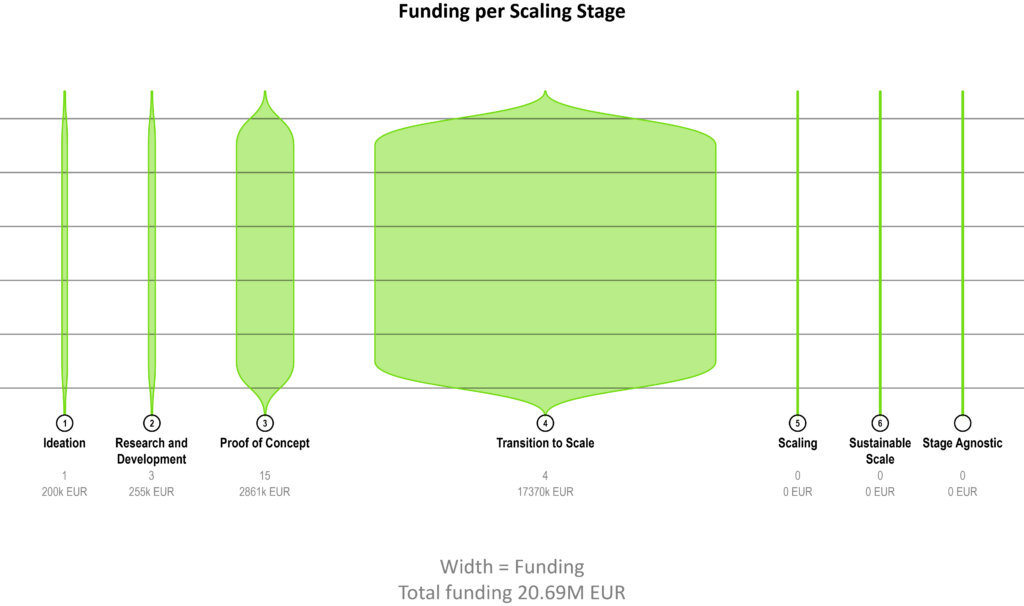

To establish an overview of the current portfolio, MFA colleagues co-ordinated a mapping process with support of tailored-made guidance from the OECD (to learn more, email us at [email protected].) We compiled a list of 23 programmes that are either fully innovative or that have significant innovation components. This mapping included data on their scaling stages and financial volumes.

Step Three: Reflect on “what is” – sense-making of the current portfolio

The mapping exercise shed light on how investments are distributed along the different scaling stages. In Iceland’s case, these are mainly concentrated in the proof-of-concept and transitioning stages. Commonly, small donors with strong partnerships tend to invest in earlier stages to provide catalytic funding for solutions that can be further scaled by larger funders, national governments and other institutions. This is because investments in later stages usually require significantly higher and diverse forms of venture support.

Yet, despite Iceland being a funder with a comparatively small Official Development Assistance envelope, the country currently concentrates its innovation investments in later scaling stages. MFA staff and partners noted that this is largely skewed by a programme supporting reproductive health and rights and one focussing on water and sanitation. Moving forward, there was consensus that a diversification of the portfolio would better align with Iceland’s comparative advantages, including its strong local partnerships and its relationships with larger development funders, positioning Iceland as a catalytic player.

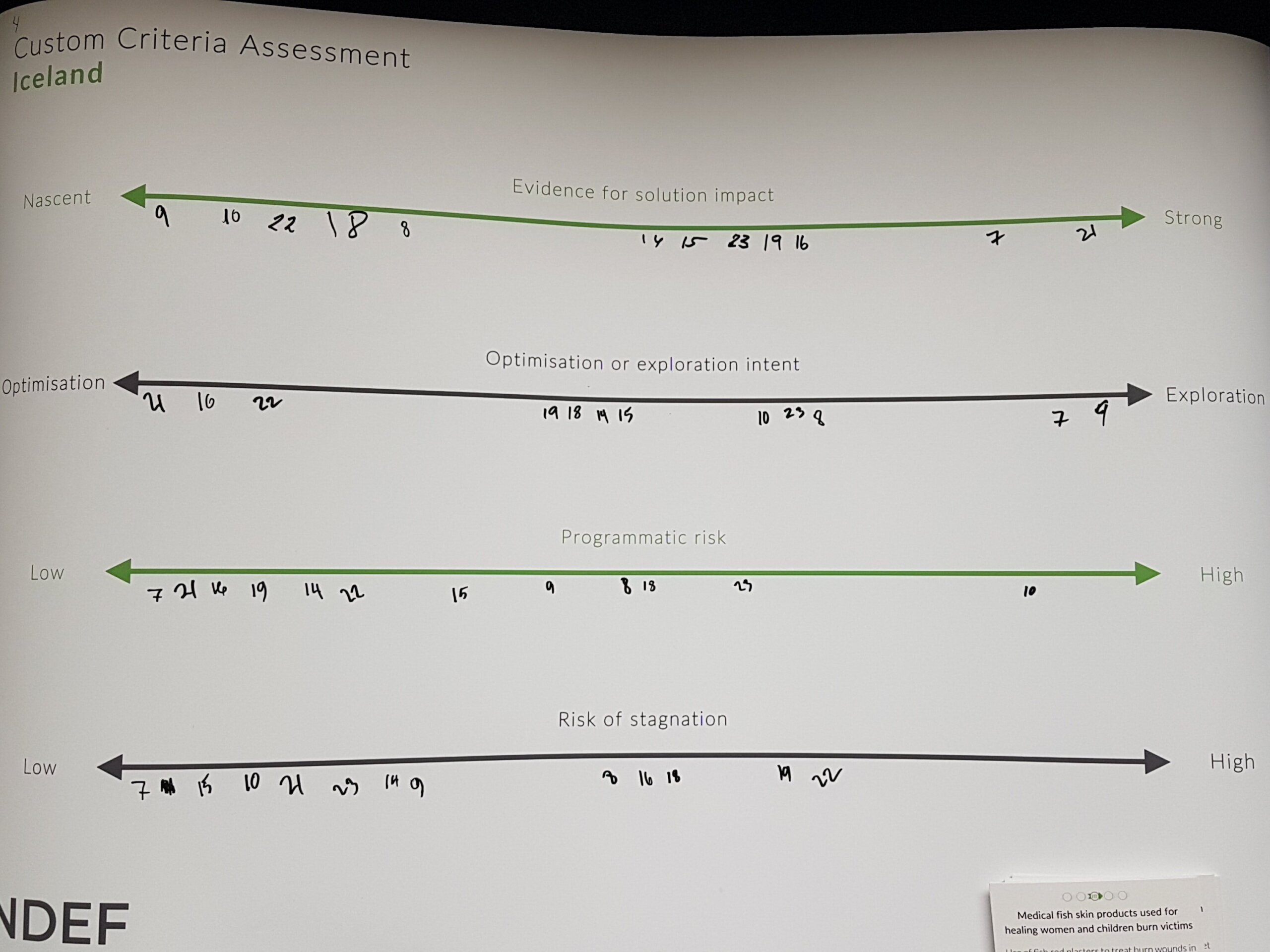

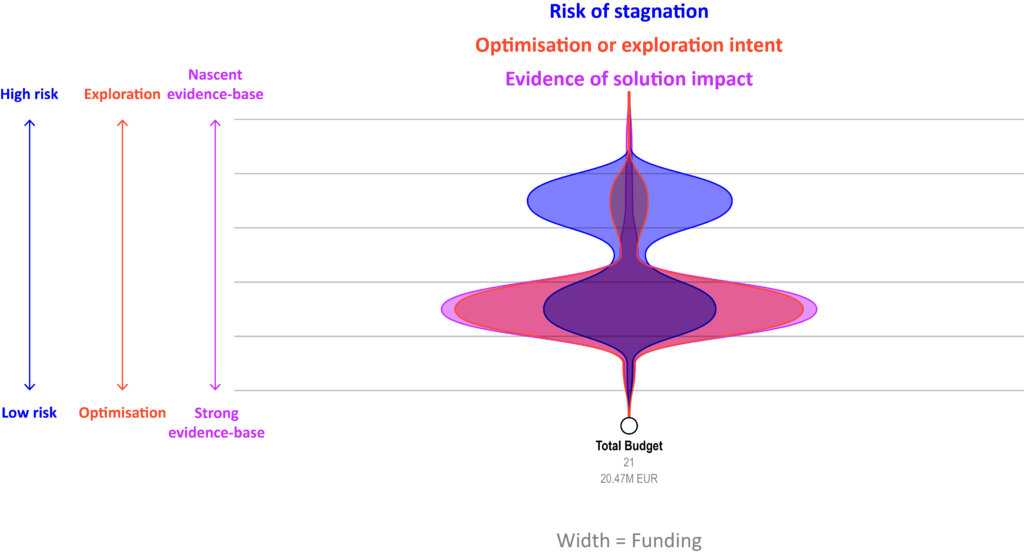

Then, MFA staff and partners assessed each programme and portfolio item against the ‘custom criteria’ (see blog Part 1). These ratings are the result of a collective deliberation of MFA staff and partners, reflecting on each programme, its attributes and where it is positioned on scales pertaining to the custom criteria. This produces data that allows MFA staff and partners to observe the portfolio from a metaphorical balcony.

The picture that emerged is that the majority of Iceland’s investments seeks to optimise current ways of delivering development assistance. Relatively little investments pursue the exploration of new pathways to achieve development outcomes and to explore emerging challenges.

The current innovation portfolio features a relatively strong evidence-base. This is unsurprising as the majority of investments focus on transitioning innovations to scale. If Iceland were to continue on this path, the strengthening of monitoring, evaluation and learning processes of innovations invested in could ensure that further scaling-up support is solely provide to innovations with compelling evidence of success.

The portfolio features medium programmatic risk, yet considerable risk of stagnation. Development and foreign policy professionals in the Ministry for Foreign Affairs recognise the complexity of development challenges and increasing pace of change. Innovation programmes in international development organisations are best placed to explore these practically, to invest in research and development, test out new opportunities in order to remain relevant. Yet, in Iceland, the current innovation portfolio does not live up to this potential to learn and adapt.

The importance of diversifying the current innovation portfolio distribution, investing in earlier stages, exploring new pathways, and addressing risks of stagnation were therefore clearly brought to the foregroundby MFA staff and partners.

It also became clear that all parties involved can benefit from a clearer framing of innovation and a formulation of its value in the context of the Icelandic development co-operation. The discussions on the ‘custom criteria’ provided a good basis to further develop common language on what matters on the global strategy level.

Step Four: ‘Now what’ – evolving the global portfolio

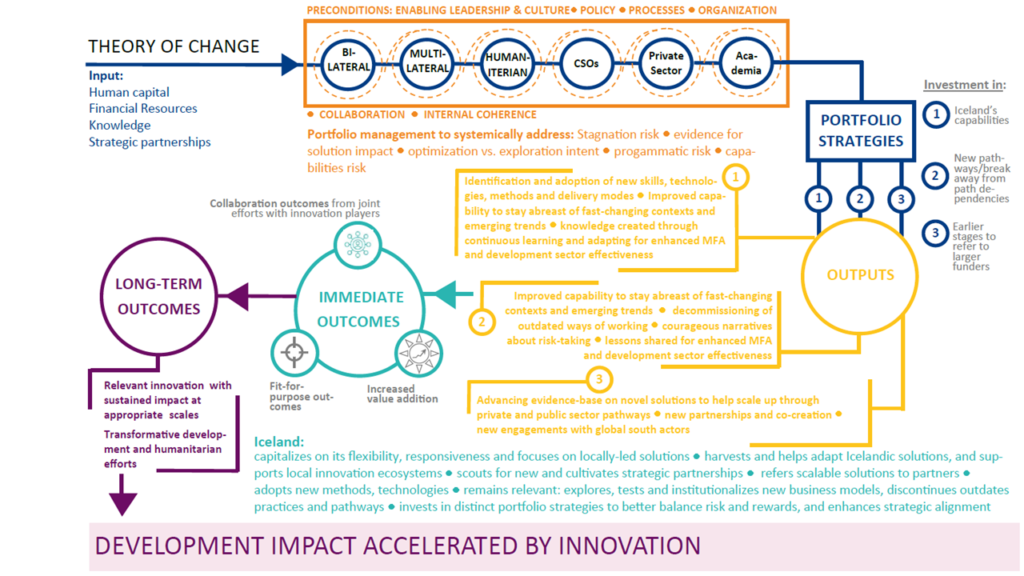

Following the workshops, the OECD team produced a portfolio brief, summarising insights and recommendations. The MFA core team is now working on taking a number of concrete steps to put a portfolio mechanism in place. As a first follow-up action, the team developed an updated ‘Theory of Change’ to better understand the effects of Iceland’s innovation investments on the country’s development co-operation priorities. This reflects portfolio strategies, jointly developed with the OECD team.

The outline below depicts several investment and change-logics, based on the prioritsation of trade-offs.

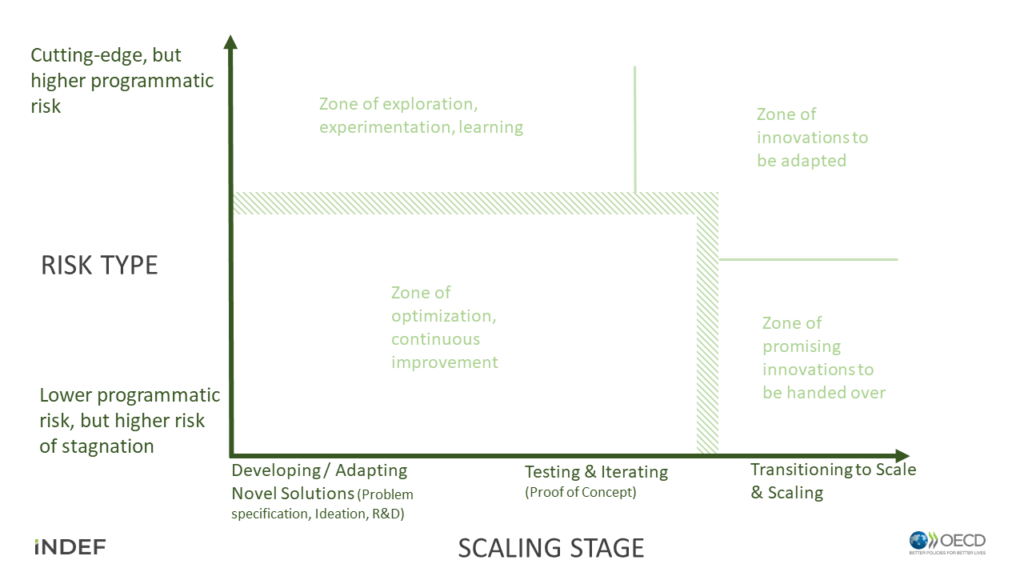

Another next step the MFA team is working towards is the endorsement and utilisation of a tailored portfolio framework to help set and codify innovation investment targets and monitor progress through regular portfolio reviews. The below framework, jointly developed by the OECD Innovation for Development Facility and MFA Iceland core team members, serves to set targets. For example, how much percent out of the entire innovation envelope will be focused on ‘the zone of optimisation’ vis-à-vis the scaling stages.

To keep track of investments and funding decisions and utilise such a framework without cumbersome additional mapping exercises every year, the MFA team is working on institutionalising an innovation marker in its current system.

In addition, the MFA are integrating regular scalability reviews into business as usual, such as programme design and review exercises. Furthermore, the Ministry is adapting existing guidance and will work alongside partners to establish clarity and a joint understanding of what “sustainable scaling” looks like and which innovation programmes could meet the criteria.

The joint collaboration allowed us to focus on the entire, cross-thematic and geographically diverse portfolio. The individual units of analysis were programmes. In many of our discussions we reflected on the ‘projectification’ of development co-operation, the lack of suitable financing mechanisms that support long-term trajectories. Not only for scaling specific solutions but portfolios that address a variety of factors of a complex challenge: regulatory, cultural, service-related and more. The challenge of how to design and manage portfolios of interventions and innovations that pursue a shared strategic intent in a specific place, across organisations, is becoming increasingly more urgent to address. As deep transformations of our societies and economies are necessary in light of the climate crisis, the development sector needs new and more adaptive approaches, beyond projects.

Our collaboration did not address this challenge immediately, but it might have provided a foundation to work on this more effectively in the future as a clearer distribution of investments along strategic criteria provides the ‘legitimacy’ space for such systemic work.