A new era. What’s the role of an innovation department and how do you get one off the ground?

With staff shortages in executive organisations, the impact of digitalisation, increasingly diverted and individualised parliaments and rising public’s expectations of public services, governments are gradually recognising the importance of innovation in their goods and services. A new era has emerged with governments professionalising their innovation processes through the establishment of dedicated innovation departments. In Europe, rarely do we see so many public organisations moving in the same direction as in this moment. The front runners in this field are Denmark, Latvia and Portugal. Combining their experiences with my research about accelerating innovation processes, I would like to shed light on this critical question:

What is the role of an innovation department and how do you get one off the ground?

Front runners

OPSI’s Public sector innovation scan of Denmark highlights the country as a global example for innovation labs, being one of the first OECD countries to deliberately support public sector innovation. Some key strengths in the Danish approach can be found in the innovative culture at all levels of government.

In 2021, Portugal was awarded a European Public Sector Award for the introduction of LabX, a centre for innovation in the public sector. The mission of LabX is to contribute to an innovation-friendly ecosystem in the public administration, in order to better suit the needs of citizens and companies by promoting the renewal of public services. The jury praised the contribution to co-created public services and the increased interaction of citizens and businesses with the public administration.

OPSI’s Public sector innovation scan of Latvia also marks the country as a frontrunner in making innovation a more structural part of public administration. The interventions applied are aimed at creating a more supportive environment for public sector innovation. They vary from training on design thinking and experimenting by the Latvian School of Public Administration, to structural budget and staff for the Innovation Lab to help introduce new methods and formalising an innovation expert network.

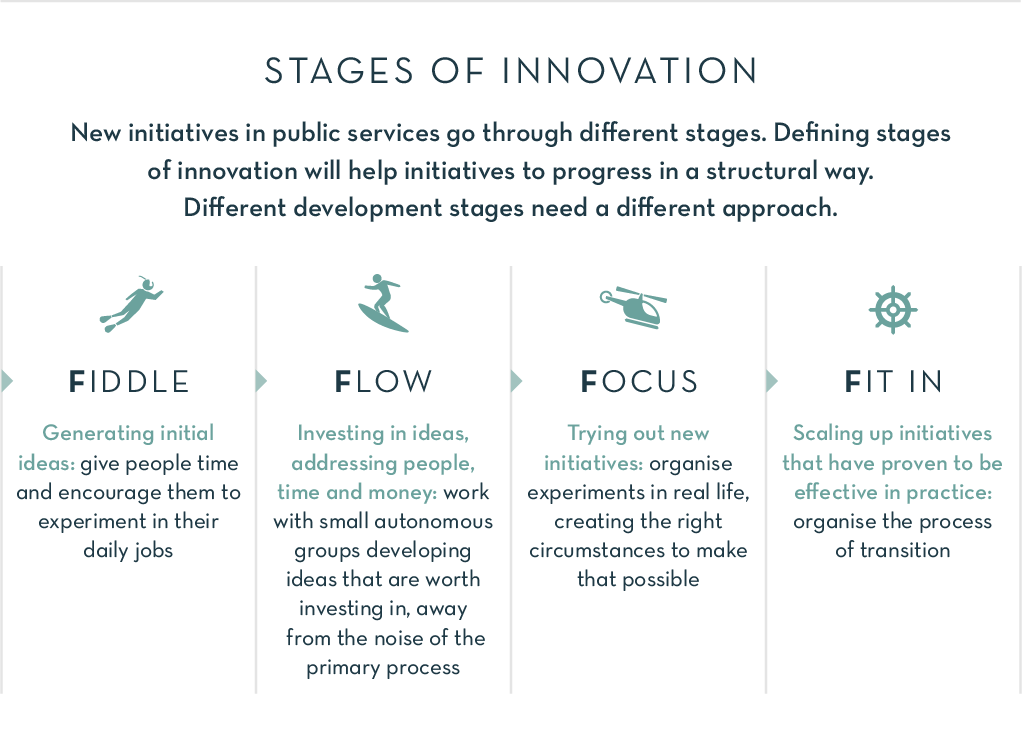

Although innovation departments can try to develop innovations themselves, results will only appear when the department adopts a facilitating role, structurally organising innovation within the organisation. An innovation goes through different stages, from people on the shop floor exploring new initiatives, to developing initiatives in small, specialised teams. Initiatives subsequently need to be further tested in the real world and scaled up when proven successful. By facilitating these stages and embedding them in a structural way, innovation departments aren’t the outside staff departments providing distant ideas. No, they will be the ones accelerating ideas from people in the organisations that really know what is necessary. They will also ensure that ideas are only taken to the next stage if they are proven to be worth it, preventing needless public spending. But what does that role mean in practice?

The role of the innovation department: From initiating new ideas to putting them into practice

In current practice, the management of public organisations doesn’t consider rolling out new initiatives in a structural way. Suggestions for new initiatives are either rejected without giving them a chance to succeed, or they fail after a great deal of effort. Defining development stages of innovation will help initiatives to progress in a structural way. Different stages need different approaches with a different involvement from the innovation department.

Fiddle

To start, innovation departments can help bring new initiatives to life by encouraging ‘fiddling around’ with new ideas. This can be done by creating the right circumstances, an environment conducive to innovation where public servants are encouraged and equipped with the tools to innovate.

New initiatives emerge ‘on the edges’ of an organisation. To make that happen, you can, for example, organise meetings with target groups about possibilities to innovate services; stimulate delegations to look at other public or private organisations that are leading the way; organise conferences, internships or research on topics, and anything you can think of in order to connect with organisations or interest groups.

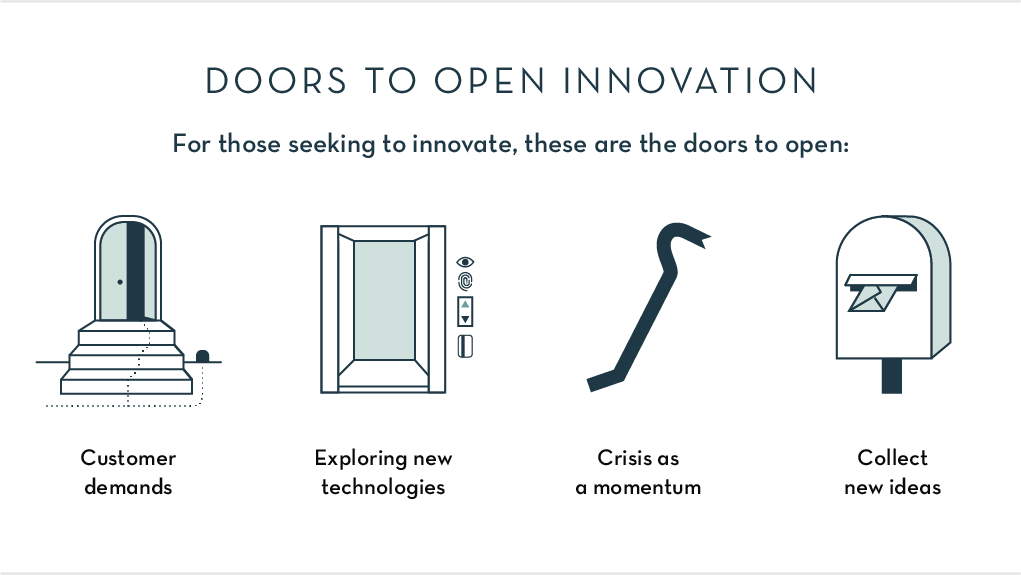

However, good ideas can also come from within the organisation. So, make sure to gather them by, for example, creating an ideas box, the idea of the month or an awards challenge for the best ideas. Ideas don’t always start with a problem to solve. They can start with a piece of new technology finding its use. We can’t live without a smartphone anymore, but only after technicians showed us their possibilities, did they become indispensable. So, make a team to check out new technological possibilities and give them the autonomy to explore and experiment.

An innovation doesn’t always have to be forced by circumstances (crises). Organisations seeking to innovate, do well to open their doors for innovation. Using a crisis to introduce new innovations can be one of those doors. However, monitoring how customer demands are met is also a starting point for new initiatives, as is organising new ideas to find their way in the organisation and getting people to explore new technologies.

Flow

Next, when initiatives seem to be worth additional investment, rarely do they make significant progress if they aren’t taken out of the primary process. The primary process is the place where our public servants carry out the primary work of the organisation: taking decisions on applications, handling client requests, providing passports, doing inspections, or any other service one can think of in a public environment. In these surroundings there is always the “here and now” demanding attention: clients waiting, deadlines to be met. Only when innovations are removed from this busy environment, will they have the chance to develop. Whether it is project teams, skunk work projects or a system in which “startups” are in place: small groups of people working with a high level of autonomy and a great deal of innovation freedom, are vital in this next stage. This is where the innovation department comes into play, providing an incubator role in its purest form, thereby creating a place for accelerated growth. It is vital that the team doesn’t lose sight of the usability of the solution in practice. Therefore, a team must always include people who know the workings of the initiatives in practice.

Focus

Large scale innovations will only be effective if they have been tried out in the real world. Innovation departments can support real life testing by providing the right circumstances. This stage is not only important to identify how new initiatives work out in practice, but also to prove the viability of the innovation. Try new initiatives in small scale settings: in one department of the organisation, in a region of the country or using pilot groups.

Fit In

Finally, in the Fit In stage, scaling will require a considerable amount of time and hard work finetuning the new initiative. Old, tried and tested working methods, will continue to be of value for a long period, competing with the new working methods. There is sure to be resistance. Therefore, to scale up, people have to believe in the new way of working. In order to get the initiative accepted, people need to be brought on board early. What helps is a small group of people who are enthusiastic and advocate the new way of working to their colleagues.

Guiding biotopes

As well as making progress with initiatives, there are other tasks to be considered for innovation departments. Innovations will not occur without an innovation-friendly ecosystem. Leaders standing behind their people when experiments prove initiatives to be ineffective, hiring people who think differently, and providing time to reflect on long term solutions are critical components of an effective ecosystem. Innovation departments can therefore take on an advisory and monitoring role, guiding biotopes and work with HR to get the right people in and support the development of leadership skills, particularly for upper management.

The right circumstances for innovation: An innovation-friendly ecosystem

An innovation-friendly ecosystem is necessary for all stages of innovation. It includes a work environment that supports innovation and the right organisational culture and mix of people.

Here are some components:

- Employees with diverse backgrounds and the right skills

- An atmosphere which builds on the engagement of people

- A culture of experimentation, reflectiveness, openness to ideas, craftmanship and people feeling safe to make mistakes

- A culture with trusting leaders that inspire others to innovate, that reflect on their own behavior, set the right example, give space to experiment and back up their employees when things go wrong

- An atmosphere in which information is shared by people

- An atmosphere in which monitoring takes place on innovation results

- An atmosphere with plenty of room for reflection

- An atmosphere where people dare to call each other out, striving to improve new initiatives

Spaan, M. (2019), From Containment to Free Flow, a handbook for the innovation of public organisations, Warden Press, Amsterdam

It can be done, but make sure to show the added value

Sounds difficult? Well, it can be done! Denmark, Portugal and Latvia are prime examples of governments that have developed an innovation department on a federal level, working very closely with local authorities and other organisations. The interesting thing is the similarity in the way they started, namely by picking up innovations and showing results through specific projects. It is only after a few years’ worth of results, that they are transformed into fully fledged departments facilitating innovation. So, to get things going you have to show your added value by achieving results. Only after that, can the innovation department embed itself, cultivating a facilitating role in the heart of the innovation process and work on structural innovation.

In a webinar with representatives from Denmark and Portugal they describe how they got their departments off the ground in this way. What is very important and visible in the webinar, is that setting up an innovation department can only be in accordance with the culture of the specific country which, for example, is more decentralized in Denmark than in Portugal. It is important to take the specific culture of the country into account.

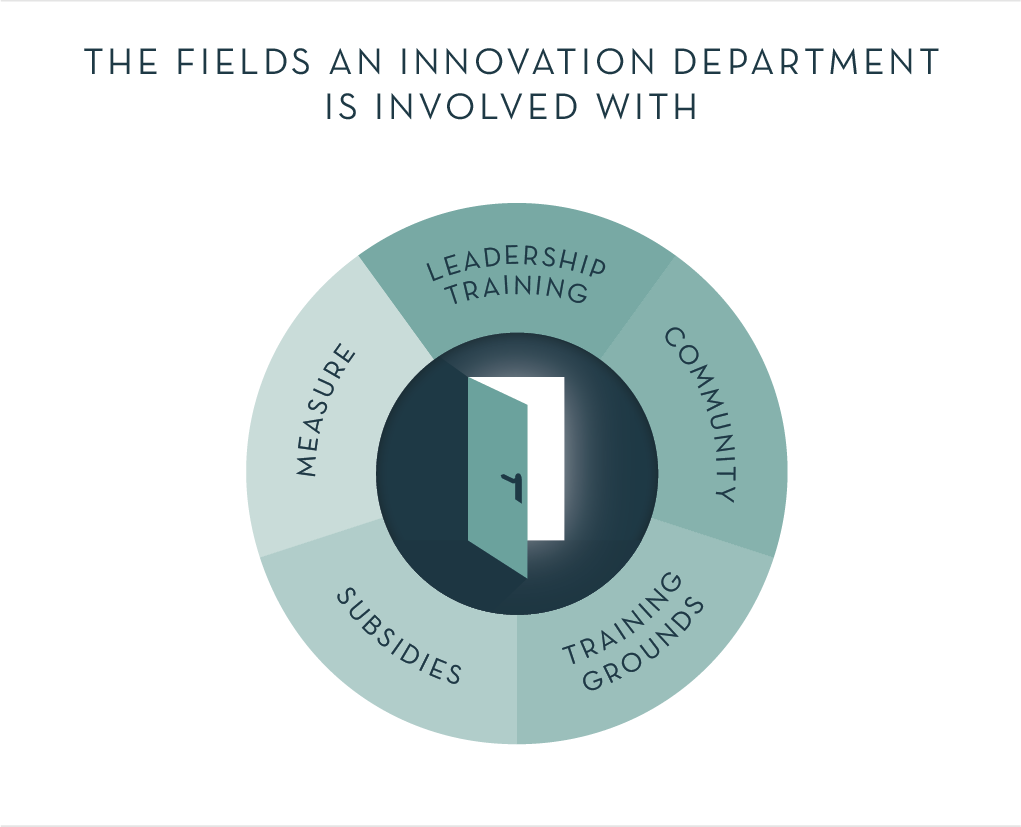

What is interesting is that, although these countries are different, their innovation departments work on the same components. Both Denmark and Portugal are working on leadership training for upper management and both are working on community building. Both provide training grounds and working methods for financing initiatives. And both are looking for ways to monitor the progress of innovations. This provides us with the fields an innovation department is involved with.

Concluding thoughts

In the new era of governments professionalising innovation processes, there are captivating examples of innovation departments in Europe showing us the way forward. Opening doors for innovation is important, on different levels. A good crisis doesn’t need to be wasted for innovation opportunities. Or, maybe better, ‘don’t waste a bad crisis’, as I have heard a senior civil servant saying, because crises can be terrifying. But there are more possibilities for innovation if you look at user demands, gather ideas for innovation, explore new opportunities provided by technological developments or, of course, a combination of the opportunities that emerge when the doors to innovation open.

Working on innovations in a structural way and looking at the different stages is important, as is providing an innovation friendly ecosystem. We have also looked at the fields an innovation department is involved with. And, of course, there is more to say about the role of an innovation department. There are different strategies for innovation to work with, for example. But in essence, the overall look of the role of an innovation department is clear.

Without a doubt, the best way to kick things off is by creating a department that initiates specific innovations itself. Subsequently, it will be crucial to gradually move into a position where the conditions for innovations, monitoring and facilitating new initiatives are central. Only then will innovations emerge in a structural and systematic way.

Finally, one more comment on a broader level, about the importance of an innovation department. It’s about ‘ambidexterity’: on the one hand, governments focusing on results and improvements and, on the other hand, initiating a continuous flow of new initiatives for future demands. This helps the innovation department succeed in its most vital task: providing continuous renewal that keeps our public organisations in sync with what we expect from them.