Mission-oriented what? A brief guide to mission terminology

This blog post was authored by experts from the OECD Mission Action Lab, a joint initiative of the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation, the OECD Directorate of Public Governance and the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate.

Despite the concept’s widespread popularity, the terminology surrounding missions can come across as convoluted. This is understandable, given that the term – which denotes ambitious, time bound, cross-sectoral and measurable policy objectives to address grand societal challenges such as climate change mitigation, biosphere restauration or tackling health inequities (more on this below) – has proven to be both deceptively intricate and remarkably versatile. It has evolved into a catch-all to describe various endeavours at different levels of policymaking, ultimately leading to confusion among even the most tuned-in of observers.

The potential origins and consequences of this ambiguity

This semantic complexity partly arises from a disparity between the theoretical underpinnings of the mission concept and its practical manifestations within the intricate landscape of real-world politics. Numerous policymakers who have sought to embrace mission-inspired approaches to shape or revitalise their initiatives and programmes have had to make some compromises along the way.

Another explanation lies in the multifaceted and multitiered nature of missions. The concept represents an amalgamation of various policy ideals and has implications across all levels of policymaking. While the conceptual thinking behind missions has largely been rooted in a top-down approach (think of the seminal example of the Apollo missions initiated by US President John F. Kennedy), many recent manifestations have been of a more complex bottom-up or middle-down character (such as initiatives driven by collaborative ecosystems or public agencies).

Regardless, it becomes very difficult to have meaningful exchanges on how to improve the practice of missions if there is no shared understanding on what precisely is being discussed. Resolving ambiguity becomes pivotal, particularly when fostering cross-sectoral and cross-border knowledge and experience sharing in what is still very much an evolving practice. This happens to be a central purpose of our work at the cross-directorate OECD Mission Action Lab, where we collaborate with and bring together experts, policymakers and mission practitioners from around the world. Moreover, maintaining clarity is essential to prevent misrepresenting the mission concept – see the ‘mission washing’ pitfall in the post ‘13 Reasons Why Missions Fail’ – which could lead to faulty inferences about the approach.

In this light, we propose an overview of some key mission-related terms and how they relate to one another, as we think of and conceptualise them at the OECD Mission Action Lab.

Taking on a challenge: missions and moonshots

Let us begin by returning to the central concept of missions. Within the context of policymaking, a mission denotes a clearly defined overarching policy objective aimed at tackling a societal challenge within a specified timeframe. Missions are characterised by a far-reaching vision with transformative aspirations. Notably, the term encapsulates both a resolute declaration of intent and a tangible commitment to take bold collective action to confront a complex societal issue. Since their realisation involves a range of stakeholders – often across multiple sectors and levels of government – they necessitate significant co-ordination.

In practice, the term mission is commonly used to describe both the objectives as well as, by extension, the frameworks put in place to reach them. For the sake of clarity, we use the term mission statement when referring specifically to the former.

One example of a mission statement is France’s ambition to encourage the emergence of a pesticide-free agriculture by 2030-2040, notably through the programme Cultiver et Protéger Autrement. While this is a bold commitment to take on a complex socio-technical challenge, it is worth noting that it does not, as is often the case, perfectly align with the ‘SMART’ criteria for goal setting (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-bound). It does not, for instance, specify a measurable target or a specific time-horizon, using instead more open-ended language. This could be due to political sensitivity surrounding pesticide reduction, reflecting the previously discussed pragmatic approach of policymakers, and the resulting theory-practice gap.

The related term moonshot pertains to highly ambitious technological ventures, accompanied by substantial costs and risks, undertaken with the goal of achieving significant breakthroughs in a specific domain. While moonshots can be considered a type of mission, they are generally more narrowly focused on scientific and technological advancements and lack the broad systemic and societal ambitions that characterise contemporary challenge-driven missions. They thus generally involve a narrower toolkit (mostly forms of R&D funding), and a narrower range of stakeholders (most often academic and industry researchers). One archetypal example of a moonshot is the United States Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Shot which aims to “accelerate innovation and spur demand of clean hydrogen by reducing the cost by 80%, to $1 per 1 kilogram of clean hydrogen within 1 decade”.

Walking the talk: mission-oriented policies

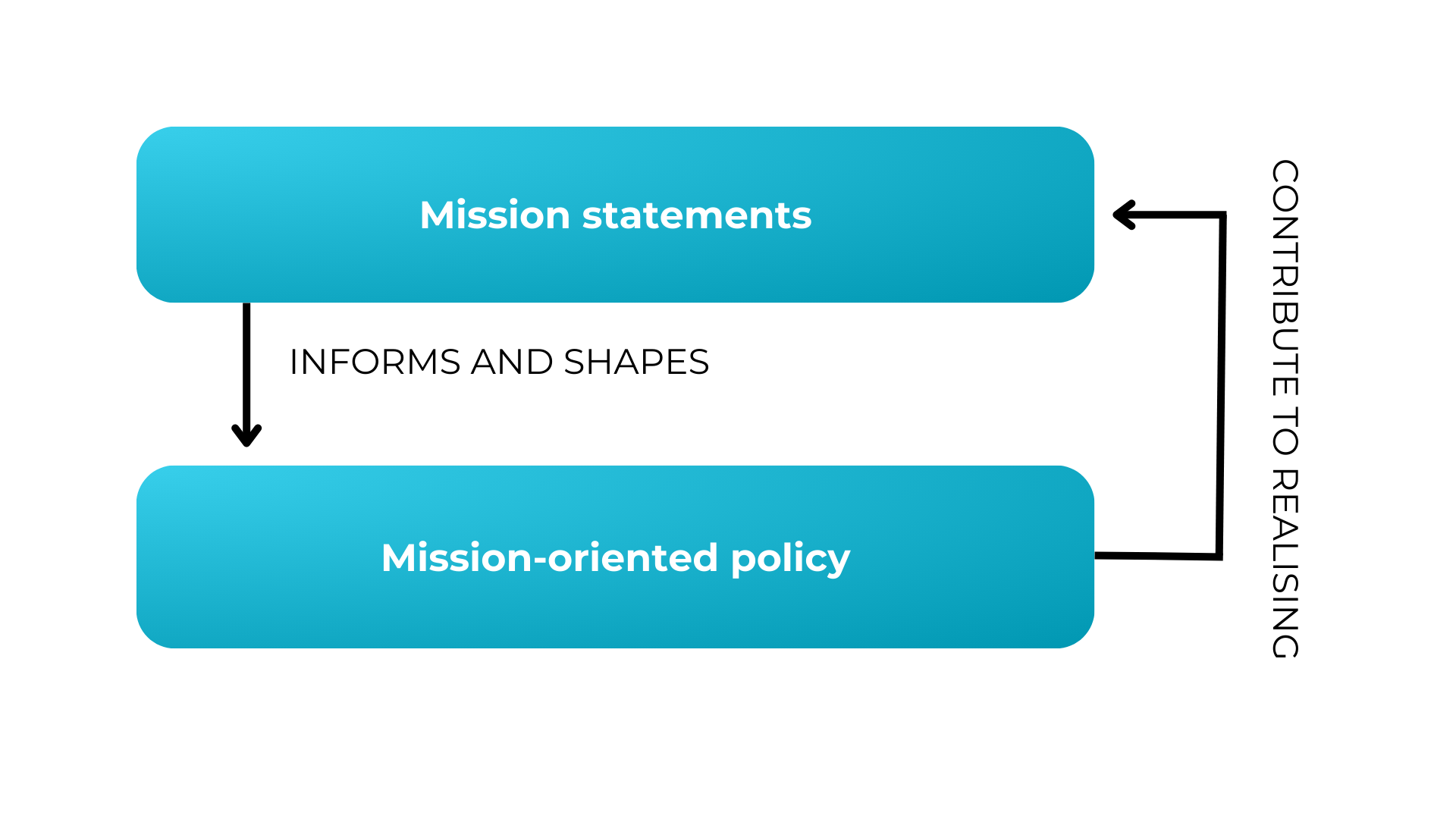

Mission-oriented policies (sometimes abbreviated as MOPs) are the policy frameworks put in place to realise mission objectives. When adopting a mission-oriented approach, policy interventions are crafted specifically to mobilise necessary resources and instruments, orchestrate stakeholder collaboration, and invigorate innovation across government and sectoral boundaries to meet the challenge at hand. Notably, mission-oriented policies can (and arguably should) draw from a range of policy domains, encompassing regulatory measures, outreach initiatives, financial incentives, research funding, or targeted investments, all orchestrated to drive progress toward the mission statement. It is, in a sense, an all-hands-on-deck approach, where the toolkit is adapted to the challenge at hand, rather than the other way around.

While mission-oriented policies can rely on employing or scaling up existing methods and technologies to meet the challenge, many missions channel their efforts towards uncovering new solutions through research and innovation. Mission-oriented innovation policy (or MOIP, although some prefer the abbreviation MIP) seek to do just that, by harnessing innovation in all its forms — be it technological, social, or public sector innovation — to propel mission accomplishment. The OECD defines MOIPs as “co-ordinated packages of policy and regulatory measures tailored specifically to mobilise science, technology and innovation to address well-defined objectives related to a societal challenge, within a specific timeframe.” Above all, mission-oriented innovation policy seeks to instigate mission-oriented innovation: innovation that contribute to the realisation of mission objectives. MOIPs can do so in different ways and come in different forms; in his typology, Larrue (2021) distinguishes between overarching, challenge-based, thematic, and ecosystem-based mission-oriented innovation policies.

No doubt due to the science, technology, and innovation (STI) policy roots of the mission concept, STI circles have been the most enthusiastic champions and adopters of the mission concepts and label; hence MOIPs remain dominant amongst avowed mission-oriented policies. Yet, it is worth noting that other types of policy – such as fiscal, industrial, education or international development policy to name a few – can also be mission-oriented, if they are aimed at addressing mission objectives.

Moreover, many policies employ different elements of mission-oriented practices to varying extent and levels of deliberateness, without using the term. For instance, in another blog post, Kumpf and his colleagues coin the term proto-missions to describe initiatives in low and middle-income countries that adhere to key dimensions of the mission-oriented approach (notably, collectively developed strategic orientation, as well as dedicated governance structures for policy co-ordination and consistent policy implementation) without having been explicitly designed with reference to the mission concept.

The STI reversal: when policies initiate missions

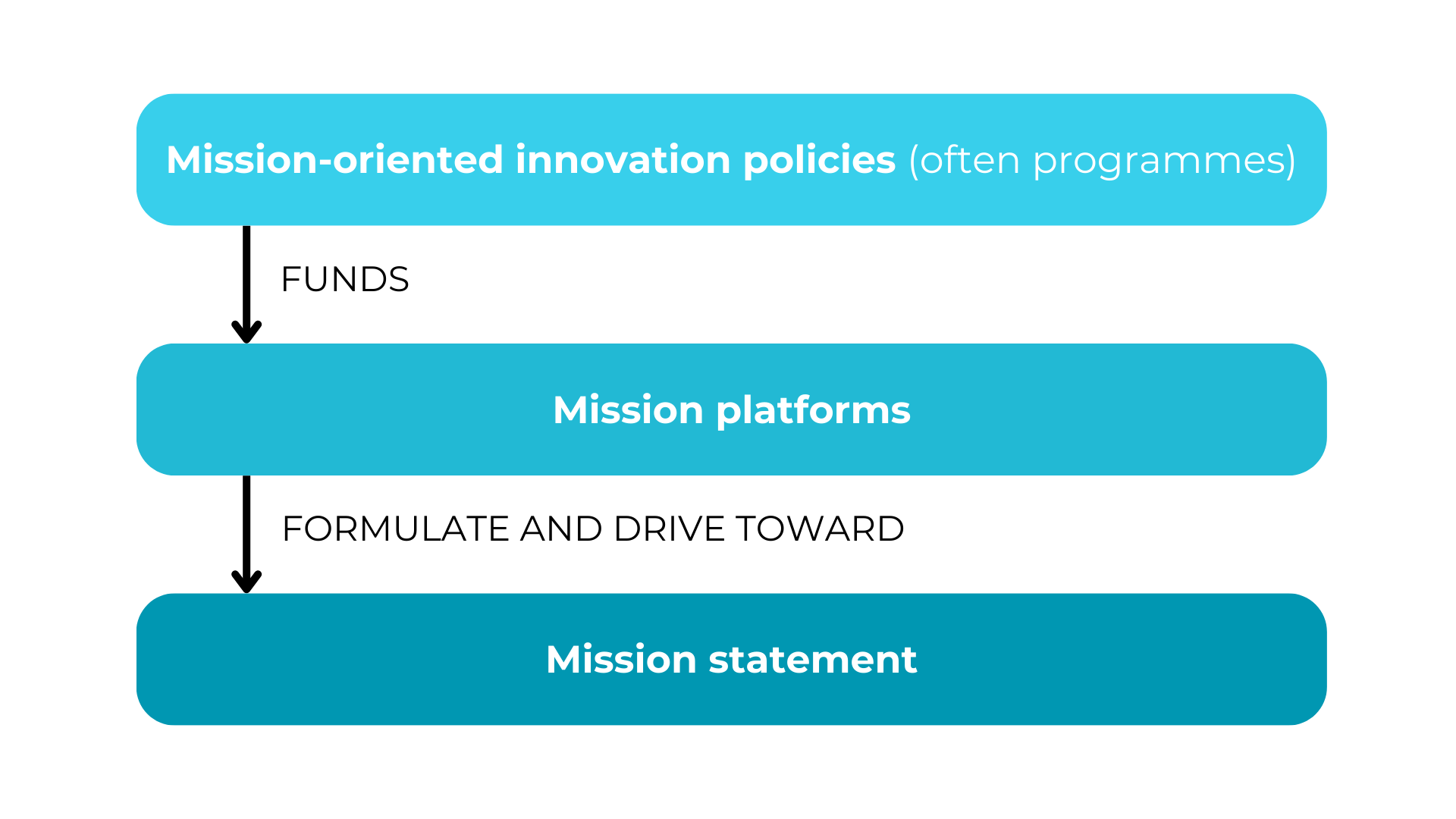

In this context, it is worth noting that many STI-driven mission-oriented innovation policies are often not “oriented” towards accomplishing a specific pre-defined mission, but rather towards supporting a mission-driven approach to innovation policy more broadly. In these cases (such as for the Horizon Europe missions or the Netherlands’ Top Sectors policy) the policies precede and set the groundwork for defining specific mission initiatives, rather than the other way around. Thus, instead of having a mission inform and shape policies, here the policies are initiating the mission.

In practice, these mission-oriented innovation policies often take the shape of programmes, typically administered by government agencies, which call for and then fund different types of mission platforms. These are support structures that convene diverse stakeholders to collaborate on a common mission statement, either formulated by the participants themselves or by the funding entity. Sweden’s Strategic Innovation Programmes (SIPs) are an example of such mission platforms.

While these more bottom-up or middle-down initiatives are sometimes colloquially referred to as ‘missions’, the term mission platform more adequately conveys that they are ecosystem-led and not (yet) positioned to harness wider government- or society-wide momentum. The hope is often that these mission platforms – which are launched and led by STI authorities – will evolve into society-wide missions, although this might be easier said than done. Indeed, OECD work on mission-oriented innovation policies has shown that expanding beyond the realm of research and development, notably to engage sectoral ministries and agencies, tends to be one of their main challenges.

The evolving language of progress

The dynamic nature of the terminology surrounding missions may present some challenges, but it also signals active experimentation and evolution in governments’ approach to addressing complex societal challenges.

At the centre of these efforts lies a search for new ways of organizing and mobilizing the public sector to proactively deliver public value where it matters most. A well-framed mission statement can inspire and galvanize, but it is only half the battle. The mission approach calls for new ways of governing, notably to enable the cross-sectoral orchestration and coordination of a wide array of actors, instruments, projects and activities towards realizing the set objectives.

The good news is that policymakers from all over the world are currently iterating their way forward to find new ways to secure systemic action to resolve systemic problems. This process might seem messy at times, but it is what policy innovation looks like.

The OECD Mission Action Lab will continue its efforts to empower policymakers to navigate these complexities, find a shared language around missions, and learn from each other’s efforts. In fact, on the 26th of March 2024, we are launching a community of practice precisely to bring together and support policymakers at different levels in taking on complex societal challenges. If interested, please fill out this short form.

Many thanks to my colleagues at the OECD Mission Action Lab and the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation for their helpful input and discussions on the mission terminology; Piret Tõnurist, Philippe Larrue, Douglas Robinson, Charles McIvor, Claire Karle, Olivia Sabini-Leite, Avilia Zavarella and Toby Baker, amongst others.

This project and blog are funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.