Crisis as a driver of innovation: Lessons from a workshop with Montenegrins

How might we take advantage of the possibilities that emerge in a crisis to build a better innovation portfolio? We took that question to a recent workshop with a delegation from the Government of Montenegro. The Montenegrins showed us what true agility looks like in practice.

Montenegro: Fledgling or Agile?

For context, Montenegro is currently one of two countries (including Serbia) in negotiation talks to accede to the European Union and this fact is an undercurrent of much of the work that the Montenegrin Government prioritises. The last few decades have been eventful for the Montenegrin Government as is the case for many post-Yugoslav governments. Montenegro became independent in 2006 so their current governance structures are quite young. Attention is largely focused on building infrastructure and transitioning to a market economy and Montenegro receives significant direct foreign investment. As a result, much of the government’s central strategy work has been quite fragmented and donor-driven, a unique challenge but also an opportunity to shape the course of future strategy. Strategy fragmentation is challenging to manage but could prevent the inertial “lock in” so common to longstanding public administrations. Many OECD countries with stable but sometimes inflexible bureaucracies might only dream of having this kind of agility and range of possibilities ahead of them in the near term.

Last summer, the Montenegrin Government passed a decree stipulating the requirements for developing strategies and established the Strategic Planning Network supporting the implementation of the decree. The Strategic Planning Network consists of members of the central government as well as a distributed group of strategy-focused staff working within ministries. This team has worked extensively with the OECD-SIGMA team on a number of initiatives, including the development of the medium-term work programmes of ministries, setting up the indicator framework for monitoring the implementation of strategies and supporting the implementation of the strategic planning system in general.

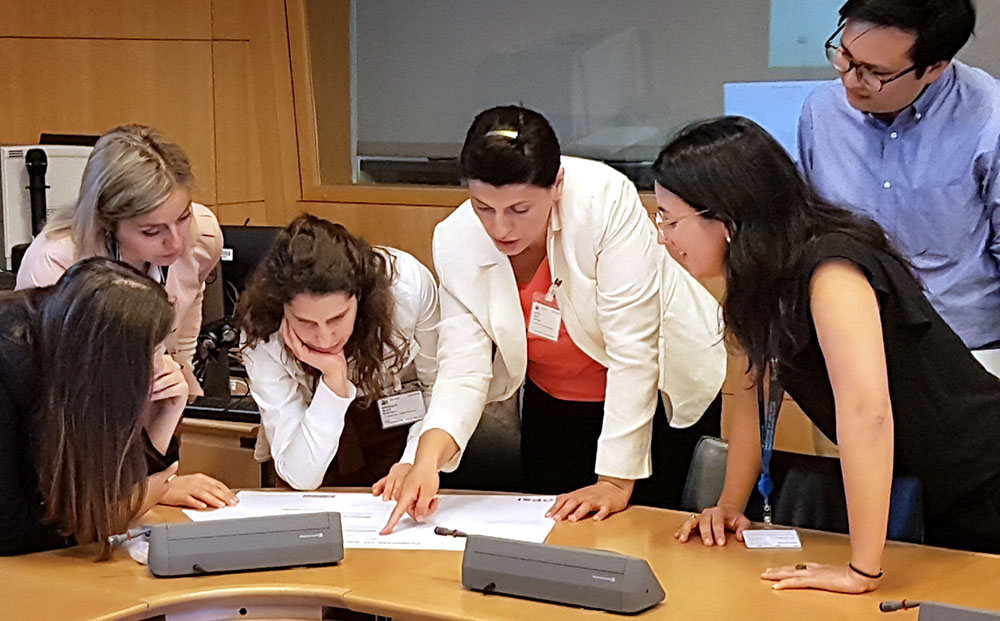

On 16 July, a delegation of Strategic Planning Network members visited the OECD to learn about recent trends in strategy development, innovation, and futures and foresight, as well as to discuss future strategy work with the SIGMA team, their hosts at the OECD.

We have tested and iterated our primordial Innovation Portfolio Workshop based on workshops in several governments (see the post about Sweden). However, it is best suited for a more “OECD-country operating environment,” where long-standing bureaucracies must contend with inertia and sometimes ossified, inflexible systems that need loosening.

In Montenegro, there is often a lack of such constraints and the natural tendency may be to respond by creating them. In a young country, this is important, of course. Consistency creates reliability, especially when it comes to things like developing infrastructure. For more on the role of constraints, take a look here.

What if a government could more quickly make sense of changes as they happen and had the tools to respond in a diversity of ways? This is what agility looks like in practice, but what so many “agile government” training programmes fail to offer. What if a government’s response to a crisis was not only “quickly put back into place what existed previously?” Imagine the possibilities for shaping the future. A shared understanding of the differing purposes of innovation in government, combined with a diverse set of levers to create change, could be part of that playbook.

Crisis and/or Opportunity

In an information-flooded landscape, focused attention is a valuable resource. Also, the focused attention created by a crisis often removes expectations of certainty, and sometimes opens space for innovation. This is an often-discussed topic in the OPSI office.

Often times, this space opens without the explicit intention of creating space for innovation—such as natural disasters, scandals, and even violent coups. One example of this was the failure of the launch of the HealthCare.gov health coverage enrolment website in the United States in 2013 and the subsequent focus on how the federal government develops and procures technology, including the establishment of the U.S. Digital Service. Would such attention have been paid to digitalisation had the very public, very political crisis not happened?

This space for innovation is very difficult to create intentionally, which is in some ways good, considering the lives and livelihoods at stake in some of the extreme cases. But creating these opportunities in established bureaucracies is essential for diversifying an innovation portfolio beyond enhancement-oriented innovation, which works well when conditions are certain. Of course, we are not suggesting intentionally starting wars but rather riding the waves of disruption and looking for the opportunities to do things better—or to do entirely new things. We are likely to see more “wild card” (low probability, high impact) events in the future, so we had better prepare now. Crises create transformation possibilities in disguise.

A workshop redesign for Montenegro

Given the contextual factors in Montenegro, we designed this workshop with a few outcomes:

- Introduce the idea that innovation is not just one thing but a portfolio, requiring different support structures and strategies

- Reinforce that participants see themselves as public sector innovation portfolio stewards

- Participants build practice with turning crises into opportunities and shifting the direction of the administration

- Participants build practice with shifting the purpose of innovation, both at a project level and system-support level

- OPSI learns how a dynamic organisation responds to crises and finds sharable lessons with other governments

In typical versions of the Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop, we tend to use Wild Card shocks to shake up perceptions of certainty in more established bureaucracies. For Montenegrins, addressing such shocks are often part of the normal operating environment for the Government.

Some examples:

In a way, the Montenegro Strategy Network has specialised expertise in adapting and responding. In advance of the workshop, when I shared these Wild Card Shocks with the OECD-SIGMA regional specialist, her response was, “Oh, they deal with things like this on a daily basis.” So, instead of shaking up an entrenched bureaucracy, we redesigned the workshop to build up their practice with turning these shocks into opportunities to adapt their strategies and shape the future development of the administration. To borrow from Dan Hill’s strategic design vocabulary, we wanted to help them quickly identify and leverage “dark matter, Trojan horses, and MacGuffins” and begin developing a uniquely Montenegrin strategy playbook. Of course, we also wanted to learn from their practical wisdom in this area so that we may share lessons with other governments in our network.

As is the case for all of our Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshops, we start with several exercises that contextualise and define the purpose of innovation at the individual and organisational level. We do this before introducing the OPSI Innovation Facets Model in order to connect the short-hand language we use in the model with the plain language and real world experiences of the participants. After that, we diverged with our Montenegrin participants from the typical workshop.

From Hypothetical to Real

For the workshop, we use deck of cards, various canvases, and even small plastic tokens to create a game-like feel. The sense of play is important for creating an environment where participants can let go of “what is” as well as rigid connections in order to try new things, a tactic often used by creators of other “serious games.”

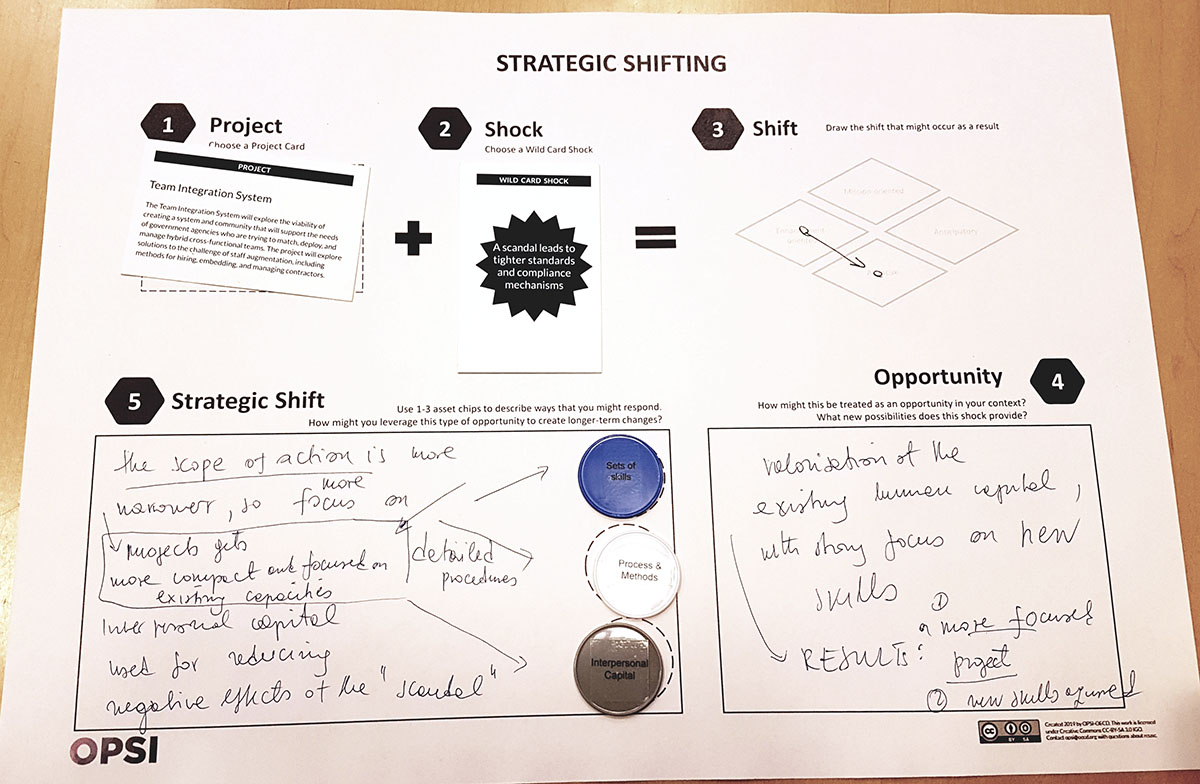

Part of the workshop card deck includes a stack of Project Cards, projects or activities that a government might undertake. The cards are hypothetical but all of the titles and descriptions are based on real government projects.

Another part of the card deck includes Wild Card Shocks, as referenced earlier. At this point, both the Project Cards and the Wild Card Shocks are familiar to government staff but not personal for workshop participants, and therefore easier to engage with in a hypothetical sense compared with projects with which participants have a personal investment.

For the first part of the activity, we ask participants to select a random combination of Project/Activity and Wild Card Shock, when discuss how the shock might change the kind of innovation occurring, based on the Innovation Facets Model. For instance, a scandal that introduces tighter compliance mechanisms might shift an ambitious mission to a more enhancement-oriented innovation activity, where easily quantifiable return-on-investment can be calculated.

The random, game-of-chance feel of the Wild Card Shocks added a lot of fun to the process and the Montenegrins responded to more familiar-sounding shocks with knowing laughter.

Then, it got real. We slowly transitioned from this hypothetical scenario to the Montenegrin context by asking:

- How might this be treated as an opportunity in your context?

- What new possibilities does this shock provide?

One example with the group included an emerging life sciences agenda project with the shock “25% of top talent leaves the country,” not a completely unfamiliar scenario for them, as it turns out (an estimated 45% of Montenegrins live abroad). While there was some discussion about attempting to lure back this top talent, the participants discussed how this scenario might also be an opportunity to invest in emerging leaders and in specialised knowledge sectors, where the lure is not as strong or perhaps even non-existent.

Then, we asked participants to consider how they could design a strategic shift based on this scenario. We asked:

- How might you leverage this opportunity to create longer-term changes?

We were no longer discussing a hypothetical scenario; we slowly transitioned to the Montenegrin context, but only after they accepted the shock and re-framed it as an opportunity. To build a bit of structure around leveraging the opportunity, we introduced the Asset Chips, which are little tokens used to represent structural levers that can be deployed individually or in combination to reshape an organisation. They include things like: Information, Budget, Sets of Skills, and Interpersonal Capital. Side note: in a small country, interpersonal capital seems to be a lever of high utility.

I was curious whether this group (or any other group doing this exercise) would have a tendency to revert to the pre-shock condition (in the case of top talent leaving, try to lure them back) or to develop an entirely new course of action (create a new talent market in Montenegro, for example). A mix of tendencies emerged, but the number and inventiveness of the new paths they designed was impressive to me. Maybe I should not have been surprised; after all, this agility seems to be a Montenegrin daily reality. Can Montenegrins build a diverse innovation portfolio by riding shockwaves alone? Perhaps this is one of many tools in the strategy toolbox, but it is now sharper than before.

We normally conduct the full Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop over two full days. However, in under 2 hours with the Strategy Network, we were able to cover a lot of ground. Not only did we introduce a more diversified way to frame the purpose and ways of supporting innovation activities in the Montenegrin government, but we also built up their practice with strategic shifts. This team was familiar with surfing waves of crises and it was a pleasure to learn from them.

The original Innovation Portfolio Exploration workshop materials are available for download here and you can download the customised Montenegro exercise here. If you have feedback on this workshop/game design or want to share your similar strategy design or innovation work, please post a comment below or send us an email at [email protected].