Organisational design in the public sector is the practice of arranging resources and supporting people in creating value or delivering on a public purpose or commitment. An organisation may be a small as a project team or as large as an entire civil service.

By Sune Knudsen, Danish Design Centre

Organisational design as a discipline has been well established for many years. Only in recent years, however, has this field begun to truly merge with the methods and mindset of other fields of design and innovation. In the public sector, working with innovation and design entails significant challenges to more traditional modes of organisation that are typically variations over the basic tenets of bureaucracy. Design and innovation, when applied to an organisational context, can drive new forms of value creation and management and leadership as well as new modes of motivation and sensemaking.

While, in many respects, the public sector is the locus of some of the most radical innovations, when it comes to the design of its organisations, it remains remarkably traditional and slow to change. There are plenty of reasons for this. The two basic ones being that,

- bureaucracy works in terms of continuously and relatively delivering basic services while being accountable to the electorate and,

- the public sector itself is seen as an element of continuity and stability in society, thus, rendering change a challenge to part of the DNA of the public sector.

Organisational design, when applied to the public sector, holds the potential to make public sector organisations more agile and adaptable in times of accelerated change, while still keeping the basic values of fairness, transparency and accountability.

Basic principles

Organisational Design that is conducive to innovation should:

- Focus on both the organisation and its context and environment – opening up the organisation to constantly exchange inputs, ideas and solutions with users and stakeholders

- Take into account how value flows through the entirety of the organisation, breaking down silos and arranging the different organisational elements so that they create positive synergies

- Create development and decision-making processes that support innovation – creating spaces for experimentation, iteration and learning

- Promote management and leadership that empower employees to challenge the status quo and that can navigate the tension of working with design and innovation when it disrupt the status quo.

State of the practice

Organisational design has long been the realm of strategy and human resources (HR) functions – a theoretical and practical discipline to a large extent separate from other fields of design.

In recent years, however, correlating with the advent of design disciplines such as design thinking, strategic design and service design the organisational implications of working in a design-based way have come into focus. And as design is viewed more and more as a core strategic capability, more attention is also given to building organisations that support design-driven practices. Thus, organisational design can both refer to the organisational implications of a design solution – as well as the way in which an organisation supports design. No matter the viewpoint, working with design methods and approaches holds both fundamental opportunities and challenges for organisations in a number of areas, the most notable of which are described in the following.

Governance and structure: When designing for innovation, governance and structure are a natural focal point. The question quickly becomes: “Where should innovation and design reside in the organisation”? In many organisations, the answer has been to set-up innovation teams (or I-teams, for short) – dedicated units with specialized competencies within innovation, be it ethnography, design, technology or something else. But over the past few years this model has increasingly been complemented by a number of other approaches; some with a more decentralized or networked model of innovation, empowering innovation efforts and initiatives locally in the organisations and others with a more accessible approach opening up the organisation to inputs and skills from surrounding organisations, users and stakeholders.

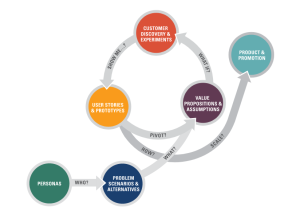

Processes: Experimental, holistic and user-centric by nature, design naturally entails different processes than the typical analytical, lateral, stringent processes of a classically effective organisation. Thus, a number of more agile processes are evolving. Originally stemming from the domains of IT-development and especially tech-startups such processes are finding their way into other parts of organisations. They are characterised i.e. by shorter, more focused development “sprints”, where relevant colleagues from different parts of the organisation gather in short, high energy and focused bursts. These approaches also radically change the pace with which decisions are made as new decision spaces are created on all levels – supported in large part by a more visual and user friendly approach to management and decision-making support – like for instance so called canvases. The most notable is the Business Model Canvas, as coined by Alexander Osterwalder.

Competencies: Working with design and innovation deliberately across an organisation typically calls for a different skill set, than the ones that characterize most organisations. The skills needed may vary across both sector and industry. But common to most organisations that apply design as an integrated way of creating value are skills such as:

- Ethnography and anthropology – the ability to professionally empathize with end-users and design structures that motivate people to do their best work

- Visual design – the ability to visualize complex systems and problems in a way that allow professionals from different disciplines to collaborate on, prototype and test (sometimes radically) new solutions

- Co-creation – the ability to facilitate the collaboration between different professions and actors.

Additionally, in order to leverage the power of design methods they need to be coupled with equally strong professionals and administrators who are able to complement the focus of experts, who have been mastering their field for many years and are sometimes unable to detect systemic changes, a kind of “expert blindness.”

Learning: Design and innovation entails working in a much more experimental way – trying things out as early in an innovation process as possible to validate or falsify assumptions and correct them as quickly (and cheaply) as possible. Working this way puts other demands on an organisation’s learning capabilities. Learning, in this perspective, not only stems from big analyses – but rather from the constant iterations of formulating assumptions, testing them, learning from them and putting this learning to immediate use in the next set of assumptions. Furthermore, organisations working like this constantly reflect on their choice of methods and approaches – thereby enacting the famous “double-loop learning”, that was formulated by Peter Senge et.al – and applying this approach not only on individual processes but also on an organisational level.

Space: Giving design and innovation a home does not just refer to a governance or structural aspect. Working in a visual, tactile, experimental and co-creative way is hard to do in cubicles and in front of individual computer screens. Thus, many organisations have dedicated spaces for innovation. These spaces may be high-tech – driven by technology or high-touch, driven by a more tactile approach. More and more, spaces are established that fuse these two approaches combining the best from tech and from the human-centred approach. Furthermore, design and innovation spaces may function as signals to the organisation and its surroundings that traditional ways of working are deliberately disturbed to spur innovation.

Leadership and management: Embedding the practices of design management and leadership is still relatively new territory for most organisations. But leading an organisation that is more open to its surroundings, that runs more agile processes and that dares to systematically experiment with its offerings needs a new type of leaders and managers. This leader is a type who is able to navigate the inherent uncertainty and tension of working in and leading processes that are open-ended – where results are not known beforehand. These leaders also have the skills to lead both upwards, downwards, sideways and outwards as new collaboration across traditional organisational boundaries are needed.

Considerations for use in the public sector

These developments hold an exceptional promise – and special challenges for the public sector, which is still, by and large, organized according to the principles of classical bureaucracy – with top-down command and control ensuring effective policy and service delivery coupled with clear accountability. All its qualities untold, bureaucracy as a form of organisation is challenged by both the agile processes, the experimental methods, the distributed organisational models and new skill sets presented above. But at the same time, these new ways of working hold the promise of making public sector organisations fit for the challenges of the 21st century. Challenges such as globalisation, digitisation and individualisation creating an ever more fragmented public with equally fragmented needs and demands. It will demand organisations that are both able to deliver on calls for mission-based, top-down directed innovation as well as bottom-up innovation stemming from the interface between citizens, businesses and the front-line staff of the public sector.

It will demand a skill set to complement the traditional ones derived from a legal, economic and political science sphere – one that comprises both the creative professions as well as the humanities.

Typical methods and tools

Luckily over the past 15 years a number of methods and tools have been developed or adapted to suit the specific needs of the public sector. To a certain extent, this also goes for organisational design.

Some of the most commonly used methods and tools include:

- Systems value mapping and canvases

- Tools and models for setting up I-teams

- Double and triple-loop learning models

- Methods for agile governance and development

What to consider when choosing a service design toolkit

When choosing toolkits for organisational design, it is crucial to remember the classical design credo: “Context is king”. There are plenty of examples of how to design individual elements of the organisation – but each organisational context is unique and thus the combination of any given elements must be adapted to the specific culture and tasks of the organisation. Furthermore, adapting organisational models is best done over time – through trial and error. Therefore, applying a more open, experimental and human-centred approach to the organisation can help you create the best combination of models, frameworks and tools for your organisation.

When picking the toolkits to be inspired from, do look for case-descriptions of how they have been applied and in what context – this will give you some idea as to whether that particular tool kit might work in and with your organisation.

Browse through some of the tools:

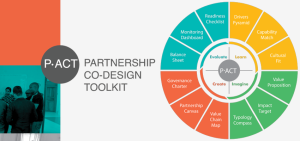

- P.ACT: Partnership Co-Design Toolkit

- The circular design guide

- Platform Design Toolkit

- UNDP – Platform-way-of-working

And view all toolkits for organisational design here.

Would you like some help?

How well-versed are you with applying these tools and methods? Do you have experience with applying these approaches in practise? If not, then the language and complexity of the working methods can be daunting. Find help and connect to a someone who has practical experience in addressing public sector challenges. But be aware so that you do not get sucked into applying their favourite method instead of leading with your unique problem or situation.

Learn about building skills and capacity

Find OPSI network members who are working with organisational design

Reach out to OPSI for guidance with organisational design

Request a webinar on this topic – top-requested topics will be prioritised

View related topics: