Sensemaking possibilities #3: refining tools and testing them against futures of government

The OPSI mission has three pillars:

- Uncovering emerging practice and identifying what’s next

- Turning the new into the normal

- Providing trusted advice

In 2020, the work that supports this mission shifted sharply; suddenly, there was a deluge of “emerging practice” as every country on earth was facing different shades of the same problem. We, in turn, experimented rapidly with ways to support governments: collecting responses to COVID-19 as a platform for examples and collaboration, seeking out incisive analyses, and designing the Government After Shock event as a focal point for stock-taking and direction-setting.

There has been a parallel deluge of analyses, insights, and recommendations for how governments can and should react to COVID-19, and how governments can and should change for the long term based on the lessons and experiences of this year. We have been looking for ways to support governments in making sense of this. We started with initial mapping tools that place ideas within conceptual space (paradigm shifts, policies, methods, behaviours), a spectrum of maturity (hunches to empirically proven models), and problem spaces (environment, social well-being, etc.).

Making sense of “Governments must do ______”

Next, we want to go a layer deeper, which also requires tightening the frame. We collected ideas that generally took the form of “how governments should change for the long-term after COVID,” but the analysis approach could be used for any idea space (e.g., “how governments can ensure social security in a restricted economy”) (in fact, the analysis model is inspired by an academic paper on films about investigative journalism).

Again, to set a boundary, we looked at the calls coming from leading think tanks, global consultancies, and members of our Dialogues Network.

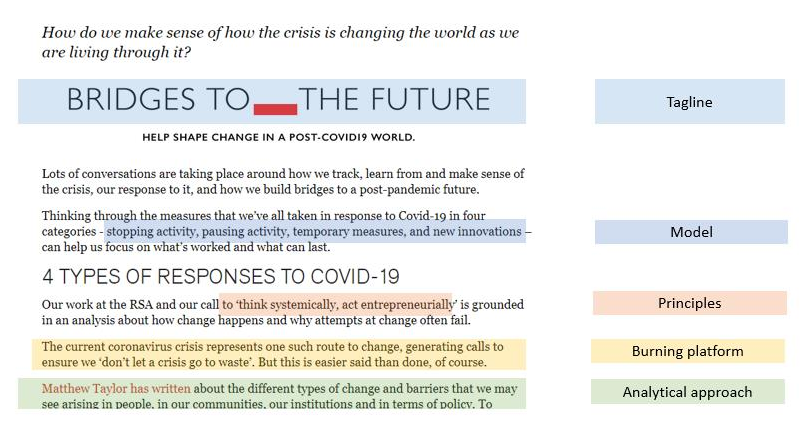

We identified a common set of narrative structures within this mass-market policy and governance analysis.

- A Tagline that provides a memorable “brand” for the idea, hinting at its purpose and potential. E.g., “Build Back Better,” “Bridges to the Future.”

- A core Action that sums up the change, usually taking the form “Governments must/should/have to… [X].” E.g., “Governments must avoid returning to old governance, processes and the way things were.”

- A Burning platform that describes why the change is urgent and the risks of inaction, often couched in colourful metaphors of what COVID-19 is such as a war, enemy, or portal to walk through. E.g, “Just as in war, to get through the Corona crisis’s tough fight stage, people will need to know what light at the end of the tunnel could look and feel like and work together to build hope.”

- An Analytical approach to support the case or make it real; occasionally this included facts/figures/trends, more often it was illustrated through examples, and most often it was absent – it seemed as though authors were assuming readers already agreed with the premise that change was desperately needed.

- A Timespan, typically immediately, after COVID, or just in the future.

- Ethical appeals, painting the need for change in the language of fairness, equality, inclusion, human needs, and compassion for each other. E.g., “In every stage however, pre and post crisis, the same people still lack power, voice and opportunity so we must also correct for the wrongs the crisis has laid bare, and ensure opportunity for those whose voices were unheard.”

- Relatedly, many such analyses proposed guiding Principles that should drive future analysis and work: e.g., long-termism embedded in short-term decision-making, inclusion across perspectives and economic spectrums.

- An Analytical model that contextualises and (usually) visualizes the proposal.

- In some cases, authors focused on specific Policy areas as specific areas for attention to either drive, or benefit from, wider governance shifts.

- The Conceptual space, as in our previous mapping: whether the changes required paradigm shifts, behavioural change, policy innovation, or methods.

- An implied or explicit concept of the Role of government, often including that it should expand (and in one case, expand while “creatively decommissioning” old paradigms, policies, and behaviours).

Essentially, we worked through articles and tagged the content like in the below:

For making sense of such analyses, there’s a subset of narrative elements that are most common and most revealing: principles, actions, and conceptual space. A note: while the analytical approach is incredibly important to dissecting these ideas, most of the articles reviewed perhaps glazed over that element and the evidence base for the sake of brevity and readability.

Principles

Of the 19 analyses that we ran through this structure, there were the following broad principles: recommendation spaces for, in effect, “what government needs to prioritize” and how often they appeared out of the set:

| Resilience (2) | Balance (2) | Transparency (1) |

| Foresight (1) | Participation (1) | Intersectoral collaboration (7) |

| Speed (2) | Humility (1) | Systems thinking (2) |

| Mission focus (3) | Rapid learning (5) | User focus (2) |

| Innovation/experimentation (8) | Flexibility (1) | Locality (3) |

| Sustainability (1) | Inclusion (1) |

There is, of course, a selection bias in OPSI’s network, so it is perhaps not surprising that innovation and experimentation was the most common priority (though it equally came from non-innovation focused organisations). As well, innovation is also a broad term that can include foresight, systems thinking, user focus, flexibility, and on. However, there are some noteworthy insights:

Experimentation and rapid learning were much more common than resilience: the community sees more change and shock coming, and the proffered response is to quickly experiment down new tracks, not to try to get back onto old tracks as quickly as possible.

References to policy spaces (environment, economy) quickly segue into the concept that it is all one big policy space and governments need to find ways to scale holistic approaches, and that even the improvement in intersectoral collaboration over the last decade is insufficient for the next one.

Lastly, two honourable mentions: the first to mission focus, the principle that people need a banner to rally behind, to give directionality to work and investments such as a sustainable economy or closing social opportunity gaps.

The second goes to locality – structuring connections between national and international responses to hyperlocal contexts – which was seen as both critical to collaboration beyond silos and a user focus, but also as a way to supercharge experimental learning.

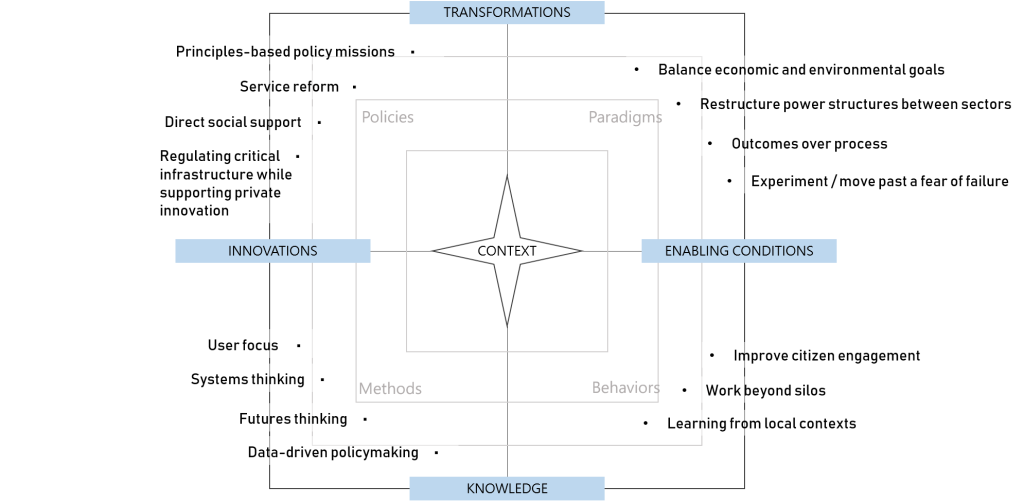

Actions and conceptual space

Actions and principles tended to flow from each other, so there is some overlap. The below is a mapping of the more common “governments must X” statement, the most defined specific actions contained in the recommendations. They could be policies, paradigm shifts, behaviours, or methods. For instance:

| Conceptual space | Example |

| Paradigm | “Ecosystems, supply chains and business systems will be fundamentally rethought, rebalancing efficiency and resilience in the light of new government regulations, sustainability goals and shifting cooperation among nations.” |

| Policy | “Regulation (e.g., protecting critical infrastructure and setting standards for sustainability and employee protection), and active participation in the private sector through financing/ownership of firms or creating demand through targeted government spending.” |

| Behaviour | “[Governments] should also redouble efforts to adopt agile ways of working, including the creation of focused multidisciplinary teams, the development of minimum viable products at speed, and the increased use of data and analytics.” |

| Methods | Learn from local contexts and the “experimental approach that is possible at a local or community level.” |

Mapped recommendations

The purpose of mapping ideas to conceptual space is that it lets us contextualize ideas within the wider ideas ecosystem. Perhaps better citizen engagement is important, but stacked up next to ten other possibilities it might not be the priority. Or, as you start to imagine the theory of change for a given idea, you can start to see how it might conflict with the goals of other reasonable approaches.

Theories of change

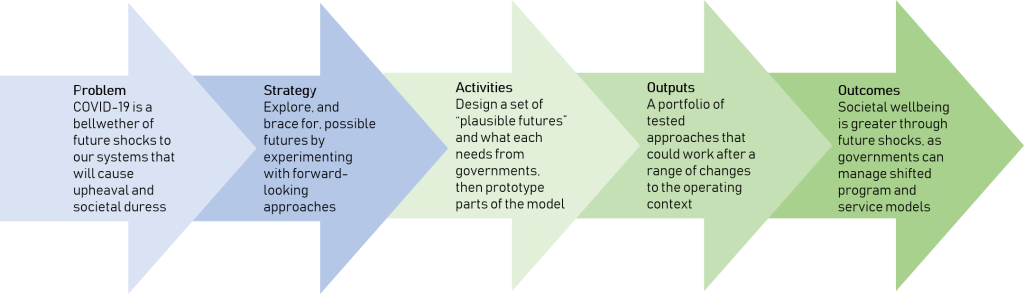

Theories of change are often strategic exercises, positioning an organisation for maximum impact within their mission and problem space. I think they are also a useful deconstruction tool for sensemaking. Especially when, as in the case of recommendations to government inspired by COVID-19, the problem is ill-defined and emergent. There are many competing ideas, and opportunity for both conflict and complementarity between interventions.

At its core, a theory of change is a structure that encourages alignment and coherence between goals and outcomes. It’s a process of personal or organizational honesty, research, and self-reflection:

- What is the problem you are trying to solve? How do you know that it is the right problem? How do you know that your analysis is sound and complete?

- What is your strategy for solving this problem? How are you and/or your organization structured to support this strategy, within the context of the problem?

- What specific activities will you undertake?

- What will happen if you do them?

- How does that solve the initial problem? What other effects might those activities have, good or bad? What changes in the long term?

Which seems a little obvious, but when you start dissecting each layer and how they relate the questions become equally obvious. For example, imagine that the goal Output is more experimentation in government. The Activity might be training, enabling more people to actualize desired behaviors. But what if the Problem is not actually capacity or knowledge, but policies and project design processes? These sorts of misalignments will come out of hard questions and deep dives into the logic model, or theory of change. Filling in the blank in this sentence is often harder than it seems, and can result in hours of discussion among a team:

“We believe that this strategy will address this problem because ___________.”

(And then “… these activities will support this strategy…” and so on.)

Most of the articles we reviewed focused on the Strategy and Activity layers, glossing over the details behind the Problem and only lightly painting a portrait of the outcomes without defining the entire cause-effect chain. Governments are then left to sift between options for actions, where the more important choices are about problems and outcomes – which is where governments can identify conflicts and complements. Taking our list of articles as an example, we could start to map them on a theory of change like this:

Each of those cause/effect changes can then be explored, and we have gone from “experimentation” as a government principle to a different problem and outcome to explore and answer: whether, and to what extent, future system shocks are likely and likely to negatively impact people without interim action.

Tools and models

Over the course of this effort to “make sense” of what governments are hearing, and test tools for re-use, we have:

- Divided ideas into policy space (e.g., environment, economy, transport)

- Assessed ideas on a spectrum of maturity (from hunches to proven techniques to scale)

- Mapped ideas to a framework of conceptual space of paradigms, policies, methods, and behaviours

- Dissected ideas by narrative elements to look for common patterns and gaps (e.g., absent problem definitions or analytical heft)

- Saw the need to work backwards to problem definitions and forward to long-term outcomes to assess different proposals against each other.

“In response to COVID-19, governments must _____”

Within the frame we selected for our own sensemaking – “In response to COVID-19, governments must _____,” we also see some patterns and insights:

- There is an actual wariness about the idea of Resilience, insofar as resilience thinking (depending on your definition and use of the term) can be about snapping back to the previous track after shocks rather than being ready to adjust to new ones

- There is a consensus among observers of the global public sector environment that continuous Experimentation, geared towards governments’ hypothetical roles in not only predicted futures but a range of plausible futures, is a crucial strategy

- There is an definite sense that a Mission-oriented approach that wraps a set of goals into a memorable banner (e.g., “double dividends of economic recovery funds going towards better environment infrastructure,” “design for maximum learning from the ground”) is required to create alignment between distributed decision-making, collaboration, and locality at scale.

Where to start, and where to go

At the beginning of this work, we were hoping to identify a simple, flexible tool that could support sensemaking of the changing world and potential responses to it. We additionally hoped that we could connect sensemaking activities happening in multiple communities through the Government After Shock events to add up to something greater than the sum of their parts.

In the end, we found that the tools always depend on the starting point.

- If you are trying to make sense of different possible actions, you could follow the path in this sensemaking series: categorizing ideas, pulling out the key parts of their narrative structure, then making sure you can map each backwards to the problem, and forward to the outcome. (We’re building an activity guide for this.)

- If you are trying to ensure that you understand a problem you are seeing, you could start by establishing your own relationship to the issue, conduct a study jam or collect stories or interviews, then use the causal layered analysis approach.

- If you are trying to gauge the long-term outcomes of a strategy or set of activities, you could conduct some scenario exploration to stress-test and imagine possibilities.

What ideas are you hearing for the future of government?

We started with a shortlist of articles from think tanks, consultancies, and Dialogue Network partners, generally framed as “After COVID-19, governments must do _____” and aiming as much as possible for a global scope. What ideas, articles, and possible futures are catching your interest? Feel free to send them to [email protected]. I can run them through the same analysis process and write an update blog on how the community-submitted ideas compared to the ones from the defined frame.