Anticipatory innovation tools and methods: Closing the impact gap

Tools and methods for innovation, anticipation, and strategic foresight are a perennially popular topic and several hundred members of the global public sector anticipatory innovation tools community gathered to take stock of promise and pitfalls of future-oriented tool and method landscape.

On Friday 12 March, OECD OPSI organised the session as part of a workshop on Anticipatory Innovation Governance hosted by the Government of Finland with the support of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Programme. Experts and advanced practitioners from governments, international organisations, and knowledge institutes contributed insights, which are summarised here.

Bridging the impact gap

This session focused on stock-taking of the tools, methods, and capacities for anticipation, how to build ways for civil servants to get started, navigating the ever-expanding universe of tools, strategic reframing, building public legitimacy for anticipation, closing the impact gap between knowledge about the future and innovative action in the present, evaluating impact of anticipation, and foresight work.

As someone who has focused on tools and methods for innovation, including through designing the Toolkit Navigator, I will be the first to stress that tools can be useful but should not be relied upon as a magic formula and the act of choosing and applying them is the most crucial step. The main insight demonstrated in this rich discussion is that a wise and skilled selection, combination, and implementation of multiple methods is inextricably linked with the purpose to which they will be applied.

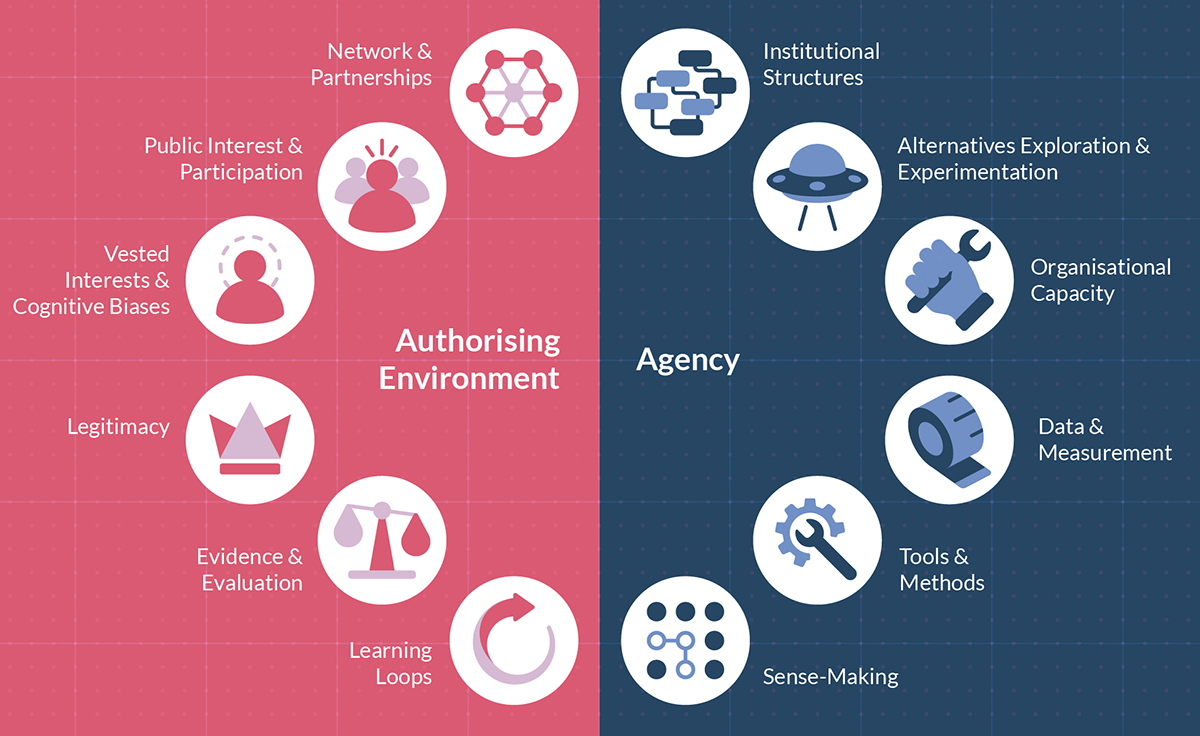

Tools and methods are one of the 12 mechanisms in the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation’s Anticipatory Innovation Governance framework, although this is not a menu of mutually exclusive mechanisms. Innovative tools and methods can also be applied in advancing the other 11 mechanisms to support anticipatory innovation, such as evaluation and sense-making, so tools and methods are not only a mechanism but a mechanism-enhancer as well. Some tools specifically focus on anticipation and foresight, but others should not be disregarded because taking action based on futures knowledge requires a portfolio of approaches.

Oftentimes, the work of public innovation units and foresight units is isolated organisationally, as many in this community lamented. A government may have significant capabilities but they are often not evenly distributed or connected to core administrative functions. Through our Anticipatory Innovation Governance work, we are helping the messy world of public administrations to close the impact gap and move from reactivity to proactivity.

Some participants discussed recent work to the link foresight and anticipation to economic values. Several promising approaches were shared, such as a “next-generation” model developed for the European Commission for integrating the value process as well as a resource exploring the value-creating systems approach for reframing how we look at value chains.

Lowering the barriers to getting started

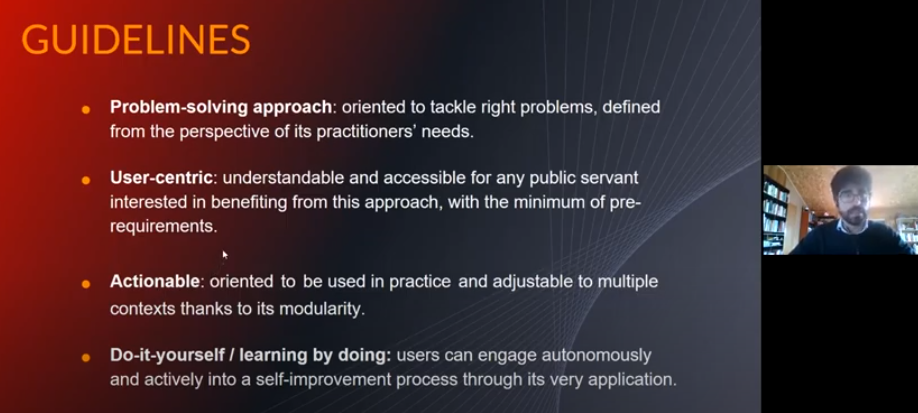

Future-oriented tools and anticipatory innovation is often difficult in the public sector, therefore this session touched on ways of lowering barriers to using them. As with many methods, especially when they are made to seem almost magical in what they promise to achieve, the barrier to entry can seem insurmountable. The process of getting started with anticipation is the key focus of Bruno Monteiro, LabX Experimentation Lab for Public Administration, a team of the Administrative Modernization Agency of Portugal, who referenced his work on the Anticipatory Innovation Starter Kit during the session, and its goal of addressing:

- Volatility, uncertainty and perception of urgency brought about by the pandemic,

- The prevalence of ad-hoc routines and reactive approaches with ‘presentist’ options contributing to a feeling of helplessness towards the future

- Limited interest and skills in future literacy

To effectively address these, the toolkit is based on a problem-solving, user-centric approach, which makes it actionable, modular and accessible to all public servants in a variety of different fields. It is structured around 4 different ways of framing/tackling the problems addressed:

- Alternative futures

- Drivers of change

- Vision

- Strategy

Bruno concluded by sharing the toolkit’s main expected outcomes which include: (i) shortening the impact gap (through its actionable/contextualisable nature); and (ii) acting as a starting point for capacity-building by generating interest and awareness among beginners.

On the topic of contextual awareness and managing complexity a participant shared a recently published European Commission field guide for decision-makers inspired by the Cynefin framework. As another participant stressed, the first and crucial step in futures work is always to co-define purpose before starting. The entry point for Bruno’s starter kit is a “problem catcher” workshop focused on framing and situating problems before choosing pathways and methods to address them. This generated a lively discussion among participants about the term “problem.”

Many tools focus on problem-solving and as some in this community pointed out, problems are often backward-looking, but need not be. Several participants noted that while “problems” are things that must be dealt with and are therefore grounded in the reality of public servants’ reality, some emergent problems are not yet felt tangibly and may be missed. How might governments capture the needs of future people and service users? A few participants suggested “future personas” to link foresight and design practices, and a few governments are experimenting with this. Another referenced the 2019 Participatory Futures Global Swarm which included hundreds of citizen-focused and public sector-driven cases (prototype map and report). Certainly, more work is needed to advance the promising work and tools for participation and deliberation so that it also addresses future generations’ needs. The application of behavioural insights to counter biases against imagining the future is also a promising but still underexplored area.

Building legitimacy for anticipation

One key yet unresolved issue came up around building political legitimacy for governments to address citizens’ current problems while unborn people are not known for their strong voter turnout in current elections. Also, in a highly polarised political environment, transparency about problems or threats uncovered by foresight and anticipatory methods may make institutions and politicians seem vulnerable—the work may be buried and the messenger denounced for “imagining the unimaginable.” In other words, the playful common saying by strategic foresight practitioners, “any useful idea about the futures should appear to be ridiculous,” does not always feel so jovial from the perspective of a podium in front of a room full of journalists. An emphasis on universal futures literacy was discussed during the session as a possible antidote (shared example of a grassroots effort involving public libraries) as well as a “stealth” approaches when using tools like serious games with civil servants (example).

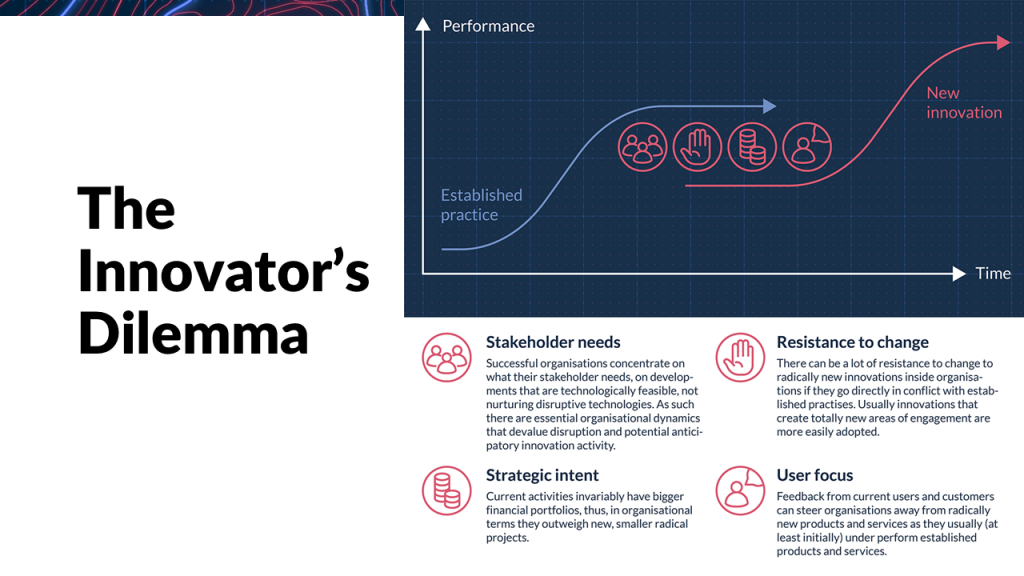

Further complicating the focus on current users is that they will want to know what is in it for them rather than people in 50 or more years. This is on top of the organisational tension between established processes and emerging realities—the so called innovator’s dilemma. Creating the authorising environment for taking on such future challenges is something we are exploring as part of the anticipatory innovation governance action research portfolio.

The age of methodological pluralism

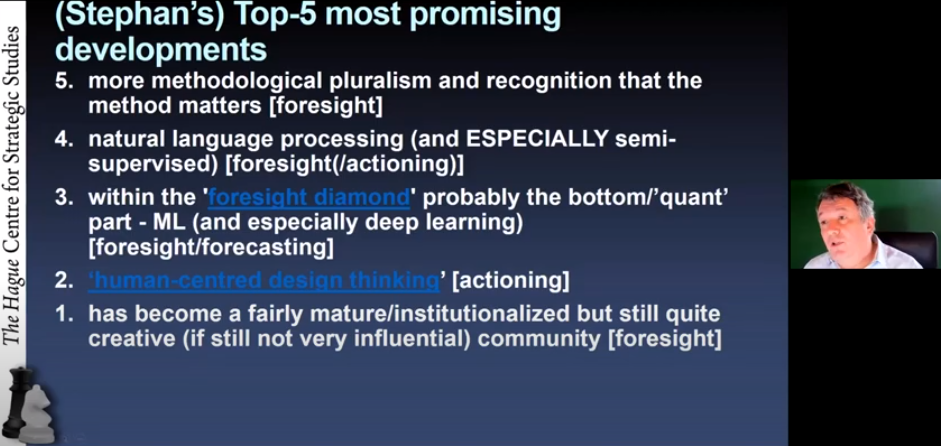

Stephan de Spiegeleire, Principal Scientist at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, expanded on the proliferation of anticipation and foresight tools and capabilities. The toolbox has exploded and there is a growing recognition that methods matter; “depending on which tool you take out of the box, the efforts will look very different.” Stephan and others emphasised “methodological pluralism,” that having a portfolio of methods is the best approach and now a feasible one given the diversity and availability of tools. With myriad tools to choose from, there is now a greater need for making the universe of tools accessible to those who have not grown up with them inside specialised foresight and innovation units.

Stephan emphasised recent advancements in the bottom or quantitative part of the “foresight diamond,” meaning greater emphasis on evidence, improvements in modelling, benchmarking, etc. Several in the community mentioned the power of text mining and natural language processing (NLP), highlighting tools to understand present narratives and how they evolved from the past, and are merging or interacting to create the future. Such tools can help quantify the qualitative aspect of language and narratives into projected futures that are used to train a deep learning neural network identifying the driving factors and combining them to inform scenarios. In such cases, 20-30 million scenarios for a single topic can be evaluated. However, as another participant pointed out, NLP gives a good view on what people are writing online, almost in real time, but not necessarily about what they will talk about in the future.

A double-edged sword mentioned by Stephan was the maturity and institutionalisation of the strategic foresight community, versus its creativity and openness. Capabilities now exist widely in governments either within departments or whole-of-institution capabilities (referenced example: Singapore), and it is a quite creative (if still not very influential) community of practitioners. An OECD colleague shared a recent global summary of foresight efforts as an example of this field’s maturity. Stephan underscored the professionalisation of the community with examples such as Millennium Project. However, this trend has its drawbacks if the community remains isolated and insular, unable to influence the core of organistaions and institutions and unable to incorporate curious newcomers. This is one for the reasons why efforts like Bruno’s starter kit are so important.

Finally, Stephan mentioned a lack of linkages to strategic and ex-ante policy evaluations and the pervasive challenge of a lack of imagination. Participants pointed out a few promising and emerging examples to the contrary, such as the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s development of a foresight training for the EU Policymaking Hub that shows how to use scenarios to stress-test policies, the recently launched Association of Professional Futurists’ task force on foresight evaluation, and the European Parliament Research Service’s commissioning of a study on stress-testing as part of its ex-ante evaluation work.

Evaluation of the impact of anticipatory tools

Mikko Dufva, foresight specialist at Sitra, Finland, then jumped into the conversation about evaluation by describing his work at Sitra. He described their three-part definition of impact: possible directions of future development are known, different kinds of futures are widely discussed, and action is taken on the basis of future knowledge. This last part, moving from perceiving to shaping the future, is an often-missing piece in the public sector, needed to cross the impact gap between knowledge about the future and innovative action today. Mikko introduced Sitra’s recently published Futures Frequency toolbox, a 3-hour workshop method for building alternative that provides an entry level to get involved in future thinking and change making, create space for imagining futures and defining pragmatic actions. It does not promise a roadmap, but rather increased capacity to think and act with the future in mind.

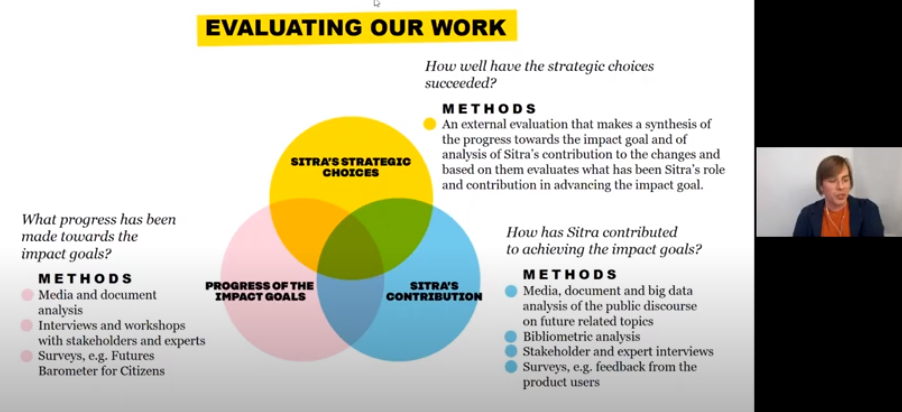

In evaluating Sitra’s work, they reflect on three areas: strategic choices (how well have the strategic choices succeeded?), progress of the impact goals (what progress has been made towards the impact goals?), and Sitra’s contribution (how has Sitra contributed to achieving the impact goals?). Sitra referenced a widespread misunderstanding about what “successful” futures thinking is: that it is done “right” when one is able to “predict” the future. On the contrary, Sitra’s success measure is rather the capacity to imagine different kinds of futures and take action today. This touched off a lively discussion about unlearning and Cassandra effects (valid warnings or concerns disbelieved by others) and the value of exploration over predictions and how action based on this will make the public sector more ready in capacity and capabilities for uncertainty, even in the case of truly unpredictable events.

The role of strategic reframing

This “imagination gap” was mentioned by several participants and Malobi Mukherjee, Lecturer at James Cook University’s Singapore Campus, discussed how strategic reframing methods can play a role in addressing this issue. Malobi stressed the importance of multi-level strategic reframing and how it challenges assumptions. She shared a paper about how strategic reframing enables individuals to challenge current assumptions and to think afresh about future possibilities, which is especially relevant for the turbulent contexts in which we operate. Moreover, she explained how an effective means of measuring strategic scenario planning’s success can be to establish whether the process is able to challenge assumptions about the business model or, in the case of politicians and public servants, about policies and governance. For this to happen, safe places for such challenging of assumptions are crucial, alongside an active engagement of individuals across different departments.

Some participants also stressed that social values are important everywhere but often kept implicit, which is a big barrier to imagining new scenarios, because beliefs about the present may be taken for granted as eternal, when in fact they are subject to disruption in the future. Some tools exist for imagining different futures, uncovering beliefs and values, exploring cultural myths, and surfacing implicit knowledge, but additional tools would be welcome in these areas.

Empathy as an asset

Sara Gry Striegler, Head of Social Transformation at the Danish Design Centre, made a final point about the role of empathy in anticipatory work, discussing how this key ingredient of design work can be leveraged for thinking about the future. She stressed that it is crucial to “put people in the future” on a personal level and to appreciate how experience triggers a human response that has the potential to transform and add new layers to futures.

To effectively choose the right tool one has to start by starting: make clear what aims are, what is the knowledge needed and what they want to get out of scenario thinking/design.

The process she outlined has three different pathways that aim at different impacts: Identify; Test (new ideas in the ‘future wind-tunnel’); Discuss (bringing together diverse perspectives to contribute to “collective dreaming”).

Sara explained how experimentation is key in all these processes, with tools needing continuous tweaking to address the learning process in a flexible, agile, and effective way. She shared some recent work by the Danish Design Centre, Boxing Future Health, which uses this approach to reimagine and redesign healthcare and welfare systems in the future. The Danish Design Centre’s recent work on Living Futures includes a kit for exploring alternative, plausible futures.

World tour of anticipatory innovation tools

The session included a crowd-sourcing activity to gather examples of where anticipatory innovation tools are being used in the public sector. Among the 45 responses from 9 countries, a few of the highlights:

- Berlin (Germany): Senatskanzlei, CityLAB Berlin, Politics for Tomorrow: A new smart city strategy development involving public imagination with multi-lingual surveys & interviews and sectoral future thinking workshops.

- Athens (Greece): Strategic planning using scenarios under volatile environment: Lessons from strategy making for the EU cohesion policy in the Ministry of Development (action learning with focal questions on the future of Greece)

- Sydney (NSW, Australia): NSW’s Shaping Futures is a foresight institution with the goal of looking at big opportunities and threats facing the state. Its main focus being on trends and scenarios, including the development of own in-house trends infrastructure to support consistent application across the state government.

- Uruguay: SARAS is experimenting enhancing anticipatory capacities using UNESCO’s Futures Literacy Framework. The process uses a conceptual heuristic frame for Anticipatory Innovation Governance to work on territories (action-learning-research) with decision-makers and a variety of different stakeholders.

This session brought together a global pool of practitioners of foresight and anticipation tools and methods and highlighted the promise of the expanding universe of tools but also the many caveats around their usage. The community also identified opportunities for this community to grow the practice in new ways to close the impact gap in governments between foresight and anticipation knowledge and innovative action.

How to get involved

You may view a recording of this entire session, contribute a tool to the OPSI Toolkit Navigator, add your reflections and comments below (requires login), or contact us to get involved in the Anticipatory Innovation Governance project or tools and methods community. To learn about other sessions as part of this workshop series, visit the overview blog here. To read more about the OECD’s work on Anticipatory Innovation Governance, visit here (short version) or here (long version).