Wasted Futures: How the ‘impact gap’ prevents us from preparing in the present

On 15 October 1987, renowned British meteorologist Michael Fish presented his usual television weather forecast, jovially remarking: “Earlier on today, apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way. Well, if you’re watching, don’t worry, there isn’t!” He proceeded to give his analysis, which acknowledged the possibility of high winds but gave no major cause for alarm. That night, an extratropical cyclone with gusts exceeding 200km/h devastated large parts of the United Kingdom and nearby countries, killing at least 18 people and causing billions of pounds’ worth of damage. The failed prediction led to a comprehensive review and upgrade to the Met Office’s forecasting systems. Fish went on to present another 30 years of relatively gaffe-free weather forecasts.

From a strategic foresight perspective, what is most interesting in this story is not the misleading forecast but the unheeded warning of a hurricane. In our practice, it would be identified as a “weak signal”—a sign of future change that is too uncertain or unfamiliar to make it into mainstream forecasts (note that Fish dismissed it), but which is worth paying attention to because it challenges our expectations (note that Fish didn’t completely ignore it). What if, despite not fully believing the anonymous woman’s augury, people had acted by taking just a few simple extra precautions to prepare for stormy weather? Of course the hurricane would have still wreaked havoc, but could its impact have been reduced?

Strategic foresight is not concerned with correctly predicting the future, although sometimes it does so inadvertently. There are plenty of foresight publications from before 2008 about a financial crisis; from before 2016 about rising populism; and from before 2019 about a pandemic starting in animals which brings the whole world to a standstill. There are many more foresight works that imagine events that never come to pass, but which can be used to help organisations better prepare anyway. Too many of these works meet the same fate as the person who warned of a storm: they are ignored or forgotten due to a perceived lack of probability, lack of immediate relevance, or lack of willingness to engage. There is an impact gap between anticipation and action.

At OPSI it is our mission and our passion to close that impact gap. The programme on Anticipatory Innovation Governance includes numerous ways in which governments can make progress in that regard. Anticipatory because it concerns producing and using knowledge about the future; innovation because it involves actions that are novel, implemented, and impactful; governance because it requires institutions and processes that promote and sustain the effort.

There is an impact gap between anticipation and action.

As a starting point for this work, in this blog post we share five tips to avoid letting the future slip through the net as Fish did.

1. Remember that improbable future stuff happens all the time

Imagine you travelled back in time 10 years, knowing what you know about the world today. Chances are that if you told people from back then about how things were going to turn out, they would find much of it difficult to believe. Why should our future be any less full of surprises? Furthermore, even if surprising events do not come to pass, couldn’t something be learned from discussing them anyway? This is how we develop so-called no-regrets strategies, which help us prepare for extreme disruptions, but which also let us make better decisions in the present. These ideas will help close the impact gap by moving from theoretical prediction to practical preparation. For example, when discussing an extreme scenario of artificial intelligence in education, one ministry on an OECD foresight intervention was able to see how promoting interdisciplinary exchanges between computer science and liberal arts was not only useful for preparing for a somewhat unlikely future but could also bring benefits to the workforce today.

2. State your purpose in using the future

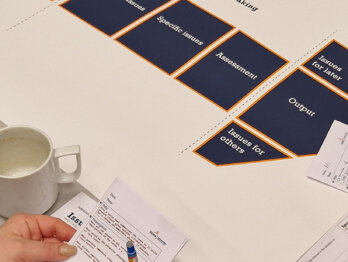

There are infinite different things that could happen in the future, so we have to narrow down a bit what we’re going to pay attention to. In forecasting, that’s done using trend analysis. In risk assessment, it’s done using probability and impact. In strategic foresight, we do it by considering how far an idea or signal about the future would challenge our current plans and ways of working. It can be very interesting to explore the future in general, but if there is no targeted user then the work has no use. Start your exploration of the future by reviewing your current actions. What plans are you currently developing or following? What are you hoping to achieve? What current predictions would have to come true for your plans and ambitions to work out? Who are the actors, and what are the factors (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, legal) which could throw your plans off course if they did something radically unexpected? These questions should guide your attention and framing, helping you close the impact gap by focusing on what matters most for your purposes. For example, a forestry commission might be very concerned with long-term environmental trends, whereas a tech start-up might focus more on changes in social attitudes over the space of just a few months.

3. Recognise that the future matters now (and only now!)

We may think that in doing anticipation we’re dealing with developments somewhere else, somewhen else. That kind of thinking has been shown to estrange our present selves from our future selves to the point that we stop caring so much about our future needs—our deferred gratification. It’s important to understand that all our thinking, understanding, and acting concerning the future take place in the present. The only time to prepare for the future is right now. When people say “we don’t have time for foresight”, they’re swapping anticipation for procrastination, even though the cost may be much higher. You may decide you will need money in the future to make a significant purchase, but you must realise that you will have nothing in the future if you don’t save a certain amount in the present. It’s the same for organisations, so when doing foresight exercises it is important to close the impact gap by remembering that the future is already here, and it matters right now!

4. Remember the future is not subject to approval

Organisations have expectations of the future and expectations of their employees. Notice the two different definitions of the word ‘expectations’ here. The first concerns predictions, the second concerns requirements. Very often, the combination of the two means that staff are required to believe in a version of the future that the organisation predicts—a kind of approved ‘official future’—and are discouraged or even censored when they question it. But the future does not care if what really happens is highly embarrassing, costly, or even fatal. So we should not care if discussing it makes us feel uncomfortable or scared. Instead, organisations can close the impact gap by building a culture of anticipation. This involves ensuring an authorising environment (through institutional structures, tools, and processes among others) and giving individuals agency (through networks, learning loops, and incentives among others) to actively explore and challenge the official future. A good example of this is a think-tank producing scenarios that are explicitly designed to test national defence strategies against a wide range of stressing conditions in order to expose potential weaknesses. You have to be cruel to your strategy in order to be kind to your goals.

5. Communicate the future in relatable stories

It’s possible (to some extent) to forecast the future in numbers, but what usually happens is that people imagine the new numbers in a world that’s largely similar to that of today in all other respects. We need to understand that the future can and will be qualitatively different—an unprecedented context or zeitgeist with entirely new challenges and opportunities for the way we live and work. To imagine that we need stories. Thinking back to the beginning of this article, what do you remember most about the Great Storm of 1987? The top speed of the gusts? The number of people killed? Or do you remember the image of a car crushed under a fallen tree? To close the impact gap, it is not enough to describe the (unlikely, disruptive) future to decision-makers. It must be made relatable and memorable. In strategic foresight, we create memories of the future through stories, slogans, pictures, videos, role play, and more. This anchors the ideas in people’s minds so they are more likely to refer back to them when taking decisions on how to act.

The present of the future

It has been said that implementation is where good ideas go to die. So it is with strategic foresight. In strategic foresight, we don’t believe that the future is out there to be predicted, but it can be imagined and explored and acted upon in the present. Only when it is acted upon through innovation are imagination and exploration worthwhile. Do you want to learn more about how to make the most of the future in present policymaking? Check out the OPSI toolkit guide on futures and foresight. Contact the Anticipatory Innovation team for more information.