Engage, test, refine – and repeat: Designing and piloting a community of practice in Ireland

This is Part 2 of a blog series on Government Communities of Practice for Anticipatory and Foresight. The series explores existing research and international examples and identifies the factors and start-up practices that are likely to catalyse new ideas and embed innovation in organisations and institutions. Read Part 1: “What does it take to set up and run government communities of practice for anticipation and foresight?”

From January to June 2023, the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) worked closely with the Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform (Ireland) on the process of designing and piloting a strategic foresight community of practice in the Irish public service. The goals were to explore the potential value and define the basic features of such a community of practice.1 This post offers first-hand insights about the practical arrangements used to induce community-building around strategic foresight in the public sector.

Five steps for community-building

There is no single way of designing and piloting a community of practice. The high context-sensitivity and distinct purposes require a flexible approach. For that reason, the initiative was structured through a step-by-step sequence of actions, becoming an experimental process in which each step was, in fact, an iteration loop – or, in another words, a community of practice sprint. This option means that, thanks to the engagement of participants, you can quickly test an insight or tool, learn from the inputs, introduce improvements and corrections in your approach, and then repeat this cycle. Throughout the whole process, OPSI played a double role of steward and facilitator.

The initiative was structured around five major steps relevant to community-building purposes, which framed and provided a sense of direction to the activities. Far from being a strict cascading plan, our approach offered the opportunity to adapt and tweak the process based on gathered feedback and the application of community-building benchmarks at each step. We organised virtual interactive sessions and invited participants to engage asynchronously in-between through digital channels. These sessions were also used to seed strategic foresight methods and knowledge, and to build capacity among members (e.g. inviting international experts to address specific strategic foresight topics or techniques, such as horizon scanning, backcasting, megatrends and scenarios).

- Step 1: Take stock of the situation. A crowdsourcing exercise provided an initial diagnostic assessment of Ireland’s position regarding its strategic foresight challenges and opportunities. This exercise helped identify areas of expertise, good practices, and ongoing initiatives that the community of practice can tap into. The session additionally revealed critical challenges and gaps impacting the use of strategic foresight in the Irish public service, including administrative silos, the immediacy of short-term and medium-term planning, and gaps in skill sets and expertise.

- Step 2: Integrate participants’ motivations and expectations. Moving forward, participants pinpointed possible areas of interest for applying strategic foresight in Ireland. The digital transition and emerging technologies, demographic challenges, and education and skills emerged as the top three priorities. These insights were instrumental in shaping a shared vision for the community of practice.

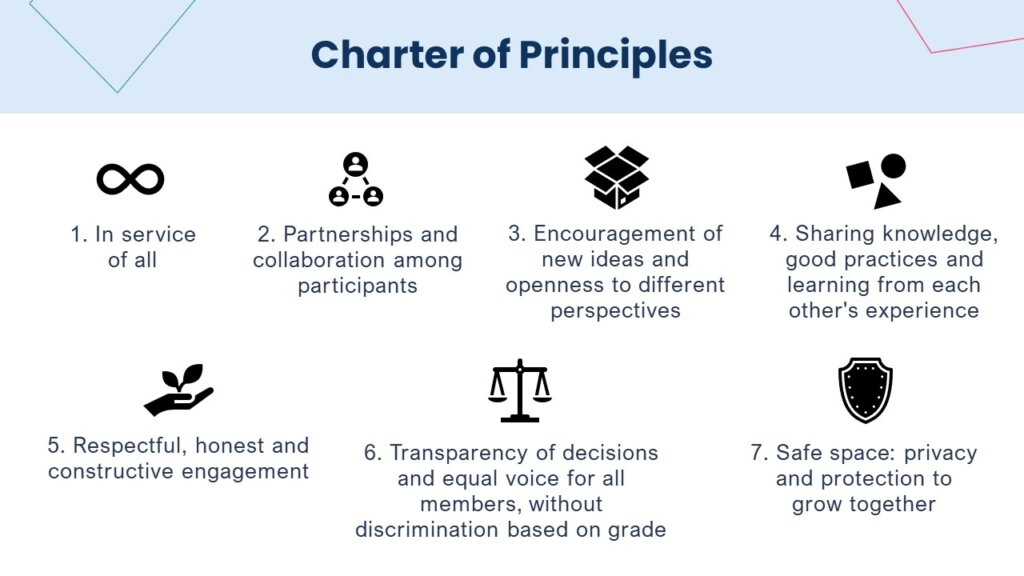

- Step 3: Set shared rules of engagement. During the third session, participants defined the seven most important principles that should guide its practices (see Figure 1). They also shared their preferences for the types of activities to be organised within the community of practice, including, among others, “sharing tools and methodological guidance”, “sharing knowledge, experience and good practices”, and “applying methods and tools together”. Finally, participants collectively defined the practical aspects of their desired ways of work, such as aiming for 90-minute sessions.

- Step 4: Support the practical application of tools – and provide meaningful results. During the fourth session, participants engaged in an initial application of an Emerging Risks Radar, identifying and characterizing the likelihood of the emerging risks associated with possible scenarios for the future of Ireland. This sped-up version of the exercise was used to demonstrate the feasibility and value of the activities the community of practice can perform and to use this tangible output to raise its legitimacy and visibility among sponsors.

- Step 5: Gather retrospective insights and prospective cues. The final session gathered feedback from the participants to evaluate this approach to community-building. The session was also used to collect participants’ expectations and know their willingness to play specific roles (such as “collaborator”, “ambassador”, “problem-solver”, “data gatherer”) on behalf of the community of practice in the future.

This experimental process provided Ireland with valuable insights and the first tangible results of this approach. In the end, the process led to the definition of a minimum viable community (or MVC), that is, an early version of a community of practice that illuminates its requirements and potential outcomes.

Good practices for community building

We can highlight a set of key takeaways that may be useful for community-building purposes and challenges:

- Promote awareness on contextual resources, barriers, and enablers. A community of practice does not emerge in a vacuum. Awareness of the context is important to navigate threats and capture opportunities. When this exercise is performed by the community itself, participants are contributing to align its purpose with their priorities, building on top of their enlarged collective intelligence, socialising the results of the diagnostic, and promoting the adoption of a more realistic problem-solving attitude.

- Summon enthusiasts – and not just experts. A community of practice is not an expert-based community. The membership should be open to newcomers and support the “legitimate peripheral participation”, as defined by Jean Lave and Étienne Wenger, that leads to growing involvement in the activities.

- Ensure that pre-set guidelines are balanced with self-determination. Requirements, boundaries, and frames of action must be made transparent to participants from the onset. Participants must have the chance to express their needs and expectations regarding engagement and define the rules of the game, such as the direction and pace of activities.

- Demonstrate value from an early stage. Modest as its results can be, a community of practice is not a discussion group, but an action-based platform. Even at an early stage, communities of practice must be driven by relevant purposes, illustrate their usefulness, and provide meaningful contributions.

- Ensure an inclusive space for all participants. Usually, communities of practice are segmented, not homogenic. The diversity of its members is an asset and a challenge at the same time. Questions of access and participation are thus very important. Participants should be able and incentivized to participate at distinct levels of engagement (or playing their preferred roles).

At the end, a caveat though: communities of practice are complex systems that resist simplistic definitions (as the next blog in this series wants to show). Instead of assuming the existence of “ready-made” solutions or “one best way” to build all kinds of communities of practice, emphasis must be placed on strategies that adopt a systemic lens to highlight adaptation, self-organisation, feedback loops or emergence as critical features of community-building.

- The OECD started working with Ireland around strategic foresight in 2020 as part of the joint project to review the Our Public Service 2020 and analyse the policy context to introduce these approaches into the public service. The learnings and recommendations from this initiative were compiled into a high-level policy brief, which highlighted, among others, the need to improve the involvement of public officials in more structured strategic foresight activities and to share learnings and evidence across the public service in Ireland. These needs were addressed during the project “Strengthening Policy Development and Foresight in the Irish Public Service”, started in 2021, with funding from the European Union via the Structural Reform Support Programme (Project 21IE08 – REFORM/IM2021/005). One of its objectives of the strategic foresight pilot programme was precisely the creation of a community of practice for strategic foresight in Ireland. ↩︎

This project is funded by the European Union via the Technical Support Instrument, and implemented by the OECD, in cooperation with the European Commission.