Strategic Foresight: A little goes a long way

Strategic foresight and innovation policy analysts Josh Polchar and David Jonason discuss what is really needed to make foresight adequate, proportionate, and regular.

Strategic foresight experts are sometimes a bit like dentists. For us, the “surgery” of strategic foresight interventions is a main part of our profession. It’s what we specialise in, and it can be highly interesting and rewarding to work with organisations who can benefit. But we make a mistake when we present strategic foresight as if it’s all about “major surgery.” We should focus more on the proportionate, timely, and regular foresight work that builds up to big benefits, just like the simple act of brushing teeth.

The inspiration for this blog comes from Josh’s childhood experience of finding trips to the dentist strangely enjoyable. He tells the story:

“My dentist was a highly affable person, with a relaxed manner and great sense of humour. One of his running ‘jokes’ was that he couldn’t wait for my wisdom teeth to emerge so he could pull them out. I would protest because my wisdom teeth have never caused me any problems. The joke worked because of the contrast in the experience for us. For him, extracting teeth was a core part of his profession, and probably a relatively interesting task that would make him money. For me, it would be an unfamiliar and uncomfortable experience that would cost me money.”

Surgeons want to do major surgery; foresighters want to do major foresight

We have seen policymakers get similarly nervous when told that they need to devote great time and resources to carry out a strategic foresight intervention. It is often an unhelpful way of presenting strategic foresight, because it doesn’t recognise the perspective and realities of the organisation that needs it. The idea of an unfamiliar, large-scale intervention lasting many months is understandably daunting. Often, people just don’t have the time or experience necessary to participate in such an undertaking. Plus, longer interventions carry a greater risk of becoming outdated before they’re even finished. The issue to be researched might have changed, or the window of opportunity is simply gone.

Just a few minutes per day can go a very long way

For most people, most of the time, large-scale interventions are not what strategic foresight needs to look like. Indeed, if we can help organisations adopt a culture in which foresight is a lightweight but regular ritual, we can make a more long-lasting and sustainable shift. Like the proverb says, “an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure.” As with brushing your teeth, just a few minutes per day can be genuinely impactful.

In this blog post, we bring together our thinking on how to make strategic foresight both more manageable and more likely to succeed. At the end, we summarise a set of tips for people of all levels of experience to make a little foresight go a long way.

What do we need: Major surgery, a periodic check-up, or a few minutes per day?

The best foresight is achievable foresight.

Major surgery

Large-scale interventions are not necessarily bad. Sometimes they’re the best option, and sometimes they’re indispensable. For an organisation facing a profound disruption or crisis; considering a significant change in direction; or tasked with a momentous decision, it is important to reflect carefully—and devote sufficient resources to doing so. In these circumstances, major foresight can be valuable. And just like major surgery, you wouldn’t attempt to perform it on yourself! Bring in professionals and choose good ones. They will help you to build new scenarios, deepen understanding, reframe strategy, or develop early warning systems. A good example of this kind of intervention is the Montfleur Scenarios, created at the height of upheaval as apartheid was abolished, and designed to guide South Africa towards a better future.

Periodic check-up

There is also value to periodic check-ups, in the same way that you might see your dentist at regular intervals. Preventive work can include discussing a set of future scenarios from a previous exercise, reviewing early-warning indicators of future change, or stress-testing the current strategy against a set of megatrends from an outside source. This is the kind of regular foresight that takes place in Finland’s government, where different ministries and committees report to each other on their futures work.

A few minutes per day

But the potential should always be considered for a little to go a long way. Just like brushing your teeth, you might not notice the difference, but over time the benefits can be significant. It can seem mundane too, but the simplicity of the daily ritual of brushing your teeth is also key to its success. It’s simple, inexpensive and anyone can do it—no need for a degree. It requires very simple tools and only takes minutes. There is of course a lot more to foresight than that (just like there is more to dentistry than brushing your teeth), but if you manage to build that moment into your daily, weekly, or even monthly routine, you are already far ahead of the pack. This kind of foresight is what we turn our attention to now.

What can we get done before it’s too late?

The best foresight is timely foresight.

It is natural for a passionate foresight expert to gravitate towards big and ambitious projects that push the boundaries of the field—a temptation that economist and megaproject scholar Bent Flyvbjerg refers to as the “technological sublime”. Yet, something much simpler and within reach can often does the trick more effectively.

Foresight can seem like a daunting task—what could be bigger than taking on the future? We might get a sense of ‘analysis paralysis’, and ask ourselves: Do we have to learn a whole set of advanced tools and methods before we can get started? Do we need to set aside at least a couple of months for this work, and is that time we have available? Maybe it’s better if we just leave it to an expert, when and if we have the budget for it?

Unfortunately, in overthinking or overengineering our foresight work, we simply do not find the time and courage to do it. But one should not make perfect the enemy of good—especially given that the 80/20 rule and the law of diminishing returns would suggest that even a small effort can have a significant impact.

This is important to keep in mind for public sector decision-makers, whose time is ruled by busy schedules, constantly competing priorities, as well as the pressures of both electoral and media cycles.

So, the questions we should really be asking ourselves are:

- What time and resources do we have, and how much foresight can we realistically get done?

- How quickly can we create something of value that we can build on later?

- What existing materials and guidance would help us avoid creating everything from scratch?

Consider whether the situation you are facing is one in which being able to bring about small doses of foresight in a timely manner, when there is a window of opportunity to act on, is more valuable than a long and polished foresight report that arrives month later when attention has moved on elsewhere. A good example of a timely foresight response is the coronavirus scenarios produced by the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy. The team used existing evidence from high-quality scientific journals to generate the scenarios, saving valuable time that was then used to put the scenarios to work informing policymakers’ decisions.

What is your minimum viable foresight?

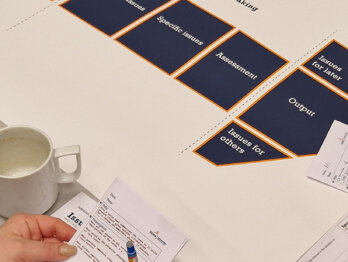

Another benefit of minimum viable foresight is that it lends itself to iteration. This kind of foresight allows us to quickly bring ideas to the fore and adapt them to the realities on the ground, using input from peers and stakeholders. During mission-design workshops in Vinnova’s Designing mission, a number of brief and open-ended speculative narratives were used to “push the participants into the future a little, and act as an early collaboration exercise.” These bitesize foresight exercises helped focus participants’ minds through the satisfaction of achieving something together upfront.

By getting some quick wins done, you’re already creating a track record, and building the credibility and momentum to justify continued efforts. Even when bringing in outside foresight experts to conduct interventions, it helps to first make a first attempt at the challenge at hand in-house, to save time when experts take the lead.

How to do a lot with a little?

The best foresight is regular foresight.

What does this mean in practice? What is the toothbrushing equivalent of foresight? It will depend on your circumstances, of course. But at its core, whether as an individual or as a team, a daily foresight ritual is about recognising that the future is already shaping up around us, whether we pay attention to it or not—so it’s worth taking the time to bring some reflection into our hectic day-to-day. One example is the regular “Foresight Friday” events organised by Finland’s National Foresight Network, which bring together futurists, policy experts, and policymakers to discuss emerging developments.

Tips for proportionate, timely, regular foresight

From OPSI’s experience and engagement with governments worldwide undertaking strategic foresight, we have identified the following good practices:

- Make the future a habit: find a daily, weekly, or monthly ritual that works and is sustainable for you and your team to discuss what’s not yet on your radar for the future. Identify upcoming decisions and events or reoccurring processes that could benefit from foresight. When recruiting, ask candidates what future external developments could affect your organisation.

- Get just enough foresight to do the job: use foresight materials—such as scenarios or megatrends—provided by others, or ask an expert to help you build a rough set that you can easily understand and refer to on a regular basis.

- Define your minimum viable foresight: a consultant (or your manager) will probably want to do something complex and shiny. You don’t want shiny, you want comprehensible and actionable.

- Check the expiry date on your futures work: review if you’ve already done enough analysis and are ready to act—remembering that the future is already underway so your work might lose relevance before it’s done!

- Make the future incremental: define quick wins in projects or subprojects that will stand alone and justify your perseverance even if larger ambitions take much longer.