New approaches to behavioural science in government

The Network of Behavioural Insights Experts in Government met in Paris at the OECD in May 2023. Over 100 delegates from 44 countries joined the network’s first hybrid event to discuss the future of applied behavioural science, including in a conversation with Professor Lucia A. Reisch and Professor Ralph Hertwig. Here we attempt to bring forward the main takeaways from that conversation for behavioural science practitioners.

Applied behavioural scientists are grappling with multiple important challenges, including how to think about complex adaptive systems, how to draw valid conclusions from research conducted in other contexts, and how to empower individuals to change their behaviour. Although the debate is maturing and our evidence base is growing, these challenges can still get in the way of implementing interventions, scaling up findings, and normalising behavioural science within public institutions.

Behavioural science in complex systems

Behavioural scientists are increasingly being called upon to consider the behaviour of complex adaptive systems, rather than just the behaviour of individuals. This is based on a growing recognition that policy outcomes are almost always the result of the dynamic and sometimes unpredictable interplay of individuals, entities, and institutions connected in a large network or system. In a complex adaptive system, many people interact in an uncoordinated way to produce system-level patterns that are not easily predictable based on individuals’ behaviour or preferences. For example, considering the public health challenge of obesity solely through the lens of individuals’ choices would miss the way obesity can spread through social networks, as well as the role of social, economic, political, technological, cultural and environmental factors in determining what food that is readily available to people.

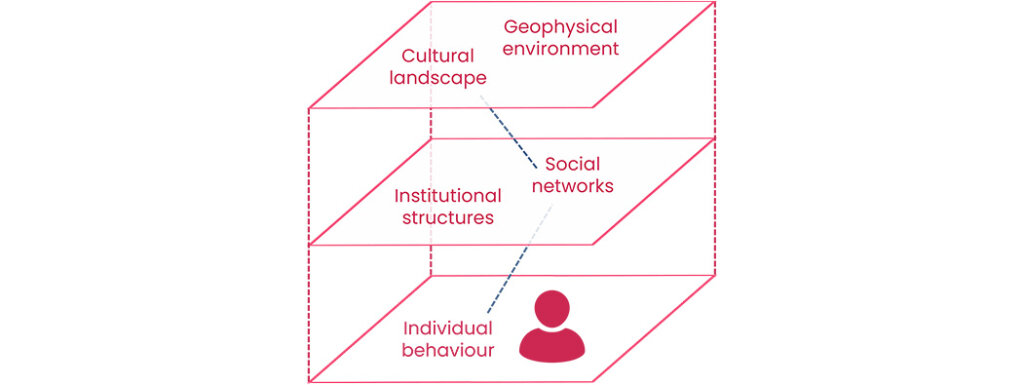

A debate between individual-level and systemic solutions in public policy has been ongoing for decades, particularly in areas like nutrition science and health psychology. These individual and structuralist views need not be seen as opposing each other, as individuals are embedded within different layers and systems that influence each other (see diagram). Considering obesity again, we can see that individual factors (such as emotions or preferences), social factors (such as peer networks and norms) and structural factors (such as economic and legal incentives) all influence obesity levels – but also that these factors are all dynamic, and constantly adapting to the other factors. We should consider all levels of analysis to understand and address complex problems effectively. We should look for integrated packages of solutions that combine various interventions, including regulations, incentives, education, and changes in choice architecture – holding all players in the system responsible for their contribution to the system’s outcome.

Behavioural scientists should invest the time and effort necessary to analyse the problem in context – for example, how individuals are embedded in social environments and systems. It takes detailed problem analysis, and the right kinds of evidence, to determine ways to address a problem at the individual and system levels. It’s crucial that we identify the underlying causes and dynamics of a problem before designing interventions – we should not fall in love with a solution before fully understanding the social and systemic context in which it would be operating in practice. For example, in its 2020 analysis of nutrition labels on food products, the European Commission integrated evidence about individual choices into an understanding of the public health and market systems.

There’s the individual embedded in different layers and different systems, influencing each other. These opposing views don’t really make sense, neither in theory nor in practice.

– Expert at the Network meeting

One promising approach is to look for leverage points within the system. For example, policymakers can explore how targeting specific groups with broad influence could facilitate larger knock-on effects.

It is also possible that incremental steps and small changes can lead to shifts in identity, norms, and acceptance of bigger policy changes over time. One driver of this can be dynamic social norms, whereby an emerging norm (such as a preference not to travel by plane) can be influential if it is seen to be a growing trend. These norm changes can be led by particular individuals or groups, grow through peer and network effects, and ultimately change the behaviours of businesses and governments.

We need to get the analysis right. Because otherwise, we are really trying to fix the problem from the wrong angles.

– Expert at the Network meeting

Finally, adopting a behavioural lens when designing regulations and systemic solutions can help policymakers foresee some of the complexities of real-world implementation, such as potential pushback from certain groups. The sustainability of a structural change can depend on its alignment with individual behaviour and its acceptance by the affected individuals.

Humility and the value of our evidence base

The conversation highlighted the need for behavioural scientists to be modest, nuanced and self-reflective, including by being flexible and pluralistic with their methods. When advising governments, the most relevant and useful evidence will sometimes come from testing interventions experimentally; other times, it will involve drawing on qualitative research, observational studies, or existing literature. Where there is a significant existing body of evidence, government behavioural scientists can translate that into a form that can be readily applied by government officials. A notable example of this being done effectively is the United Kingdom Cabinet Office’s recently published behavioural approach to crisis communication.

We should ask what method is the best one to use for the problem that we have and for what we want to achieve. Randomised controlled trials remain important, but we should also consider ethnography, interviews, and other methods from anthropology and sociology, which can help us better understand complex systems and problems.

Implementing research evidence in practice is difficult. Solutions that appear simple and impactful in the laboratory turn out to be much more complex once you try to implement them in practice. Pilot testing interventions at a city, regional, or neighborhood level can provide valuable insights to help refine solutions with real‑world impact.

Nudging, boosting and self-nudging

Behavioural science interventions can be categorised and mapped in different ways, such as UCL’s Behaviour Change Technique Ontology. One variable is the extent to which the individual has autonomy or agency in the behaviour change.

The term “boost”, used to complement “nudge”, refers to an intervention that provides actionable competencies to individuals. Nudges focus on changing specific choice architectures, such as reframing handwashing practices of nurses as a moment of patient care rather than a compliance burden. A boost might involve helping nurses understand the risks of unwashed hands, by presenting infection risks as a frequencies (‘one in twenty’) rather than probabilities (‘five per cent’).

It has been argued that boosts have the potential to lead to more generalisable and lasting behaviour change than nudges. In the handwashing study, the nudge had the stronger immediate effect, while the boost remained stable for a week, even after the intervention was removed. In another example, the World Bank found that low-touch training in cognitive behavioural therapy led to improvements in Pakistani entrepreneurs’ mental health that actually increased three months after the intervention.

Boosting approaches may be particularly promising when dealing with individuals with uncertain or conflicting goals. When individuals lack a clear preference structure, nudging them in a certain direction may be ethically problematic.

Empowering individuals with competencies is also important in toxic choice environments. When a certain context has been fine-tuned to drive individuals towards choices that may not be in their best interests – such as some fast-food stores or social media platforms – boosting can help people navigate and resist this manipulation.

Both nudges and boosts can complement each other rather than being opposed. A reminder could prompt people to use a skill they have been taught. For example, a ribbon on a car door could remind people to open it with their opposite hand, helping them spot cyclists (the so-called Dutch Reach). Similarly, the concept of behavioural capability acknowledges the role of skills and reflection in decisions made within a choice architecture.

Nudges and boosts can also be complemented by other behavioural public policy instruments, such as nudge plus (nudges with an added element of conscious reflection), self-nudges (enabling people to design their own decision environments), sludge reduction (removing unjustified frictions in government processes), and regulations targeting individuals or private companies.

We sincerely enjoyed the dynamic and thoughtful conversation between Professor Reisch and Professor Hertwig, and look forward to more excellent contributions from them and other experts to these important dialogues underway in behavioural science.

Next steps for government behavioural scientists

On 30 May the OECD Network of Behavioural Insights Experts in Government explored these questions further in a conversation with Michael Hallsworth, Managing Director, North America for the Behavioural Insights Team, who visited the OECD headquarters in Paris. Michael’s manifesto for applying behavioural science proposes ways for the community to respond to each of these challenges, as well as others, including how to infuse behavioural science into organisations and how to recognise our own entanglement in the systems and structures we are trying to change. The OECD will address some of these questions itself in upcoming publications on choosing the right research method, and on organising and managing behavioural science functions.

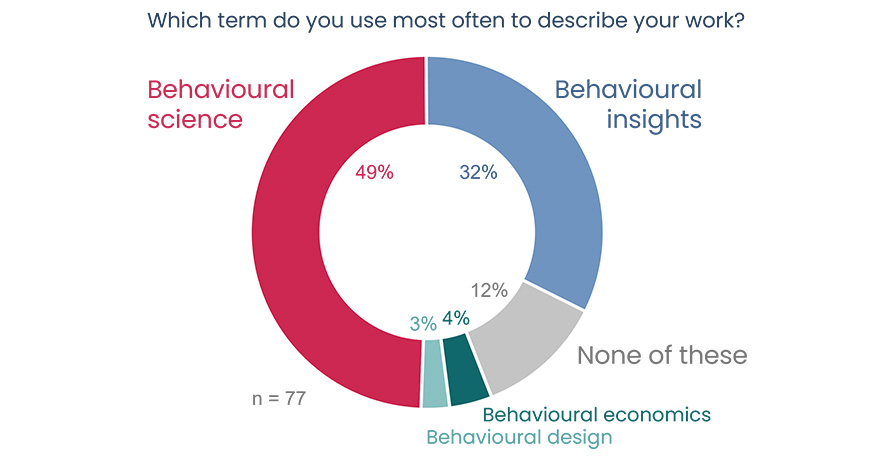

Finally, for a bit of fun, during a live session on 16 May we asked network members what term they use to describe their work. It seems that, at least in our network, the term ‘behavioural insights’ might be going out of fashion!

Further reading

Hallsworth, M. (2023), “A manifesto for applying behavioural science”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 7, pp. 310-322, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01555-3.

Hertwig, R. and Grüne-Yanoff, T. (2017), “Nudging and boosting: Steering or empowering good decisions”, Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 12/6, pp. 973-986, https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617702496.

Reisch, L. A. (2021), “Shaping healthy and sustainable food systems with behavioural food policy”, European Review of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 48/4, pp. 665-693, https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbab024.

This blog is funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the OECD and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.