Public sector innovation and COVID-19: practitioner perspective webinar

“We were trying to change the normal before the crisis – we don’t want to return to that normal” (Bruno Monteiro).

As witnessed by the growing collection in our innovative responses tracker, there is currently a surge of innovation going on in the public sector as governments adjust and adapt to the coronavirus crisis. Governments are faced with multiple dimensions of the crisis – health, economic, social – and novel responses are being tried and tested with great speed.

But what is it like for public servants trying to do things differently at the moment? And how can we make sense of and learn from this time to ensure that the upheaval caused by the crisis is used constructively, and not just to return to a situation that was already flawed?

On May 7, the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation held a webinar, with the support of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme, to hear from three members of our Network of National Contact Points about the practitioner perspective on what has been happening in public sector innovation during the current crisis. This post provides a detailed write-up of the event, as well the recording and the presentation slides.

The broader context

Edwin Lau, Senior Counsellor in the Public Governance Directorate at the OECD, helped to establish the context for the event. Edwin noted that no one could deny that we are in need of more innovative and agile government – but that it is also important that this is a deliberate and systemic approach rather than one where anything goes. This is what the work of the OPSI team, and their colleagues in the Open and Innovative Government Division at the OECD is about ensuring.

Edwin reflected on how governments need to take a three-dimensional approach, one that considers the:

- Short term – ensuring that governments are responsive and have the systems in place to deal with the crises, to respond quickly when needed, and have available the necessary intelligence and data to act effectively

- Medium term – that governments create a map for recovery, a plan to get back to some sense of normal, whether it be in regards to public finances, transboundary collaboration, or ensuring that the temporary suspension of rules moves back to a restoring of the rule of law. However this step requires that governments absorb and build on the lessons of the crisis

- Long term – the ability to respond to future shocks, and what vision(s) there might be for the future of the public service, and the relationship of the public sector to the broader economy and society given the upset and upheaval of this crisis.

The OECD is working to support government on all of these three horizons, as evidenced by the materials being continually updated on the OECD coronavirus hub.

Setting the scene

I then introduced the panellists for the session:

- Lene Krogh Jeppesen, Senior Consultation with the Danish National Centre for Public Sector Innovation

- Pierre Schoonraad, Head of R&D at South Africa’s Centre for Public Service Innovation

- Bruno Monteiro, Coordinator at Portugal’s LabX Experimentation Lab for Public Administration.

In the next section of the webinar I spoke about how a crisis behoves us to learn in order to make sense of and give purposed to the losses and the costs that we have all suffered. A key part of the role of the OECD is to collect and share such learning, recognising that learning is going on in every jurisdiction in a truly global crisis. In addition, the speed of learning as crucial, given that in this instance lives can depend upon the spread of better practices and solutions. Thus, it is an opportune time to consider what the crisis is revealing about public sector innovation.

One step taken by us at OPSI to support that sharing of lessons was to launch an ‘innovative responses tracker’ to the crisis, which, with the support of the Centre for Public Impact and GovInsider, has captured relevant examples from around the world. These examples are a mix of scale and scope, and cover a range of areas:

- Infection control or tracking measures

- Improving communications / providing targeted information

- Service delivery in a crisis / adjusting to context

- Social solidarity and ‘caremongering’

- Leveraging and redeploying existing resources and solutions

- Open calls, hackathons and other challenge-mechanisms

- Adaptive responses by legislatures

- Collective learning and sense-making

- Structural responses and possible longer-term shifts.

Some of the initiatives seen thus far – e.g. the introduction of virtual weddings and granting of wedding licences remotely – help to signify the extent of the transformation and disruption occurring, when something so human and social has been digitised.

Of course, the cases collected thus far are not comprehensive – many people have been busy doing rather than recording. And for some of these cases we will not be able tell their merit until after the fact, and some types of innovation may not become obvious or noticeable for a while.

Country experiences

The panellists were asked to help provide a richer picture of what was going on by discussing some of what had been happening in their respective countries.

Bruno spoke about how innovation was taking place in different ways, identifying three sorts of innovation activity across the Portuguese administration:

- Inside-out: where the state tries to answer the public’s needs. An example of this was “We are on” which provides a single point of contact, centralised information and access to relevant digital services. Part of its purpose is also to help combat incorrect information that might be circulating

- Outside-in: where civil society is helping to provide answers. An illustration of this was the tech4COVID19 platform established to provide mutual assistance, e.g. helping smaller local businesses to shift to selling online in order to adapt to the changed circumstances

- Within: initiatives addressing public administration. This was highlighted by the development of a collaborative workplan, including things such as strategies to help connect digitally with citizens, or guidance on leadership in terms of crises. These efforts have often helped accelerate or make tangible things that were already in track.

Lene then spoke about the Danish context and highlighted how the crisis had the potential to exacerbate or magnify some existing issues, such as social inequality across the country. Lene observed that at the moment we’re all only just scratching the surface in terms of what’s being seen, and we are likely to see much more revealed over time. Lene broke down her categorisation of innovative responses in the following ways:

- Communication and product innovation: this has been easier to notice, for instance in the Prime Minister giving dedicated press conferences for children, digital consultations for health, chatbots and so on. Often these were drawing on readily available technology and thus could be (and were) implemented quickly

- Service innovation: Lene noted that it was likely such examples would come into their own over the weeks to come, and illustrated with the example of a municipality that had developed a local ecommerce platform to assist local business during the lockdown period

- Organisational and process innovations – these are just starting to be seen, and include a number of collaborative efforts, including the 3D printing of face shields as personal protective equipment by the maker movement, such that they were matching some of the larger established companies that changed their production line towards face shields in what they could produce.

Lene discussed how the potential for radical innovations was just coming to light, including conversations around more in-depth reform of the health system based upon the experiences and insights gained throughout the pandemic, rather than previously developed plans. It was also noted that there had been a quantum leap in digital transformation, building off an already good starting point in Denmark, where a lot of the infrastructure was pretty much established when the crisis began. The crisis has been different because it has been for a prolonged period for all parts of the system – leaders, staff and citizens – meaning that everyone has experience in new digital working habits. This means that new opportunities have opened up or are being identified, such as the potential to transform thinking about libraries (libraries in the cloud).

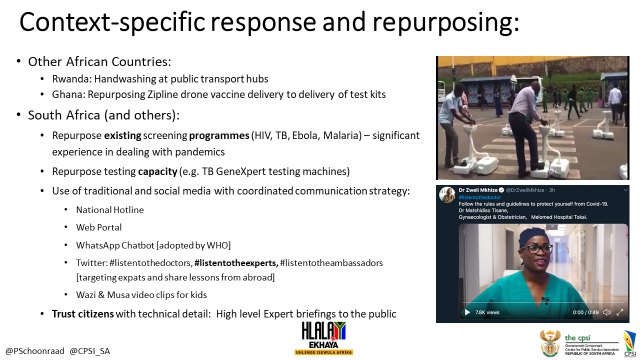

Pierre then spoke about what he had witnessed in the South African context. Pierre noted that he had seen some very context-specific reactions in Africa, such as Rwanda quickly rolling out handwashing facilities at public transit hubs or Ghana adapting vaccine deliveries by drone to deliver test kits. He noted that Africa had a lot of experience with pandemics, and thus had a lot of community health workers who were trained in testing and treatment, and thus there had been a lot of repurposing of existing infrastructure. An example of this was the repurposing of TB testing machines for COVID-19.

Pierre also discussed how there had been a lot happening with regards to social media, with campaigns to encourage people to listen to doctors and experts, to help with trust issues. There had been careful work done to provide the technical details behind the public decision-making, so that people could have faith in what was being decided upon. There were also targeted messages to kids.

A wave of innovations

Combined with the initiatives covered in the innovative responses tracker, the panellists’ responses highlighted that there was a surge in innovative activity, with a range of things being accelerated or unlocked by the crisis. Why might this be the case?

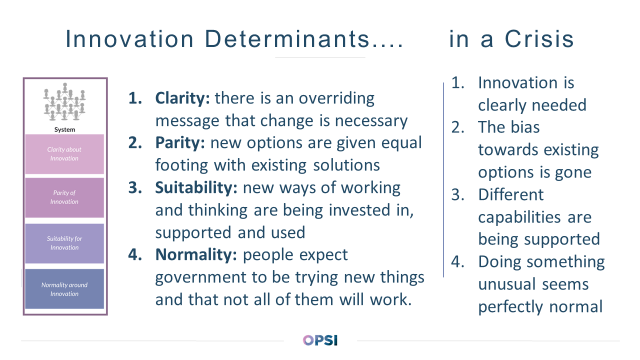

I noted that previous research by us at OPSI had identified four determinants – key things that influence the extent to which innovative activity occurs. The crisis helps to demonstrate and highlight these.

For instance, innovation at a system level has been found to be influenced by the extent to which there exists:

- Clarity – is there an overriding message that change is necessary? Well, in a crisis, innovation is clearly needed and the call for new responses is one of the top priorities of most governments

- Parity – are new options given equal footing with existing solutions in decision-making processes? Well, in a crisis, the bias towards existing options is gone, as existing solutions have revealed themselves to be inadequate or insufficient

- Suitability – are new ways of working and thinking being invested in, supported and used? Well, in a crisis, different capabilities are being supported and invested in, often at scale

- Normality – do people expect government to be trying new things and do they recognise that not all of them will work? Well, in a crisis, doing something unusual seems perfectly normal, and doing what had recently been normal would not even be allowed in many contexts now.

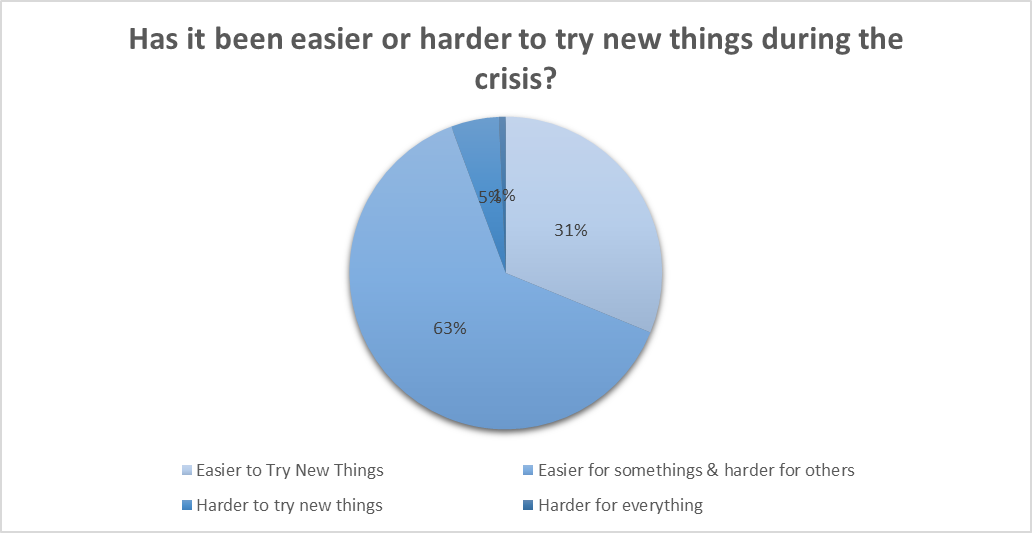

The very fact that we are seeing a lot of innovation now suggests that a crisis is indeed conducive for innovation, though this does not necessarily mean that the act of innovating is any easier. The audience was asked to consider the question “Has it been easier or harder to try new things during the crisis?” while the panellists reflected upon a second prompt.

Crisis as a driver for innovation

Noting that it can be hard to innovate at the best of times, I asked Lene “is it actually easier to innovate when it is far from the best of times, when there is a crisis?”

Lene noted that some things have been easier and others harder. For instance, digital transformation has been much easier. On the other hand, there have been challenges from having systems in crisis mode, with the resultant centralisation of decisions at the top of the hierarchy, making decision about things that need to be implemented at the frontline in fast-changing contexts. While not certain yet, it is likely that innovative work not related to the crisis has been put on the backburner. There will also need to be questions asked about existing innovation work that may need to change now – have the problems changed after the last two dramatic months?

Lene observed that the crisis had given increased legitimacy to the topic of public sector innovation, as the crisis has shown those that saw it as some sort of luxury that it is actually a necessity. This might, over time, mean that we see an increased innovation capacity and more radical innovative ideas and practices in relation to other crises or challenges (e.g. climate change and ageing demographics). There will also need to be a second look at innovation labs and innovation ecosystems. Lene shared a quote from a colleague – “Our colleagues are more innovative now than they’ve been for a long time.” The crisis has especially equipped those parts of the public sector with an already existing strong innovation capacity to have a better lever to shift innovation to more strategic discussions.

Pierre spoke about how the crisis had provoked both enthusiasm and frustration when it came to innovation. At the individual level, people have realised that the only way to deal with the crisis is to innovate, and so a lot of innovative activity is happening. However, there is also a lot of frustration because the specialists have been closing ranks, firming up the organisational and sectoral silos, as parts of the system are sceptical about the innovations from other sectors.

Pierre referred also to another tension highlighted by the crisis – isolation of teams versus the breaking down of barriers. For instance, the pandemic had highlighted limitations of the current healthcare system, allowing for new perspectives – including how social innovators and the maker movement can play a role. Long-standing and firmly rooted barriers have been broken which will allow for the new, and yet the isolation experienced by teams had changed team dynamics, making the innovation process harder. People have needed to intuitively navigate the spaces between differing systems, which has not been easy.

Bruno also spoke of the ambiguity of the current moment and how it both helped and hindered innovation. He spoke of how the crisis had solved the problem of the Gordian Knot, unlocking innovation by forcing people and systems to practice what they had been preaching for some time. The crisis has acted as a magnifying lens in showing the value of innovation in real, practical terms. Bruno also discussed how the crisis has illustrated that innovation ecosystems are very real things, rather than abstract, with several groups and communities helping the public good in many ways, such as through crowdsourcing of ideas or solutions. Bruno stressed the importance he believed that open government approaches had had in allowing this, creating trust in public governance that could be drawn upon at a time of need.

At the same time, Bruno emphasised that there had been a range of challenges that the crisis had introduced or exacerbated when it came to public sector innovation. Misinformation or even just dispersed and fragmented information circulating made it hard for governments. In addition, in the face of a crisis it is natural for there to be many solutions created, some very quickly, which risked diffuse, rushed and atomised reactions rather than a cohesive and systemic approach. There were also specific challenges driven by everyone working remotely and the rapid shift to digitising everything, ranging from loneliness to new issues that can arise from digitised public services.

In short, all three spoke of contradictory dynamics, rather than the crisis being a straightforward unrelenting force for public sector innovation. This was reinforced by the poll result which highlighted that most people felt that the crisis had made it easier for some things, and harder for others.

Different types of innovation at different times

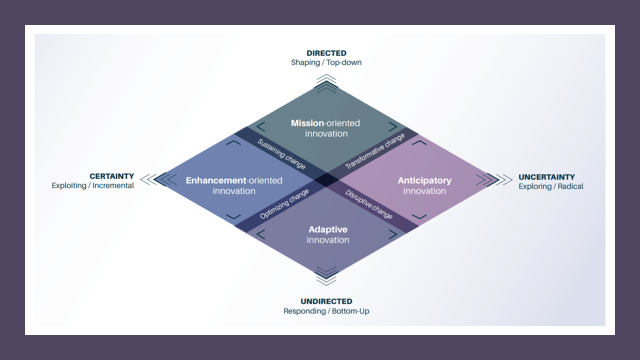

The innovations seen thus far have varied in the scale and degree of innovativeness. One model that can assist in thinking about the different types of innovation that are occurring, and the different purposes underlying them, is the OPSI’s innovation facets model.

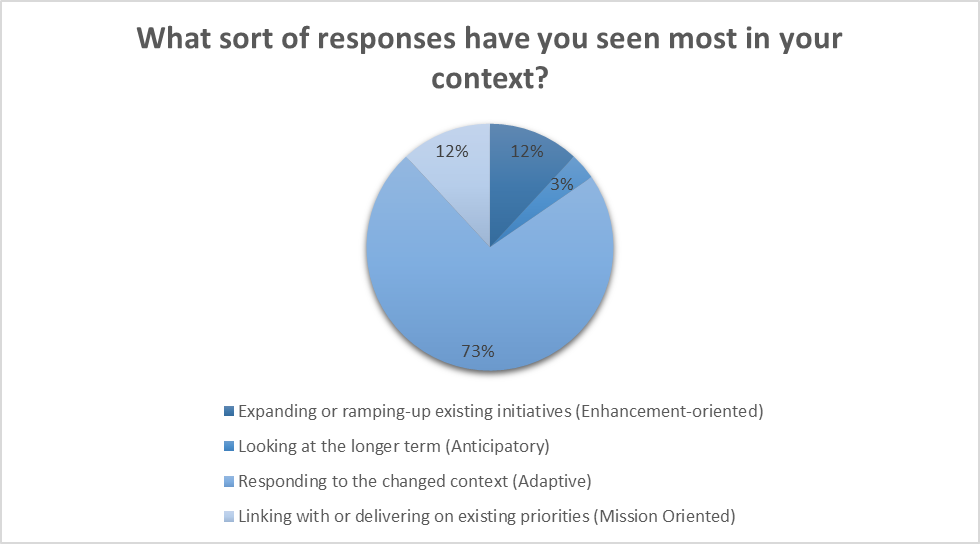

Many of the innovations tracked thus far have been adaptive innovation (responding to a changed context, such as digitisation of services), though there have also been many enhancement-oriented initiatives (such as leveraging and scaling some existing solutions). There have also started to be some more mission-oriented innovations, such as governments trying to leverage the situation to pursue particular priorities (such as making industry support conditional upon compliance with climate goals). The more anticipatory innovations are likely to be harder to see at the earlier stages of the crisis.

The panellists were asked about trying to innovate across different horizons and catering to existing, evolving and emerging needs, especially during a crisis, when the demand and attention is on the right now.

Pierre answered by talking about how the crisis had revealed that the normal planning processes are not sufficient for such situations. It is evident that we cannot simply return to a pre-COVID19 state, so there is a need to engage with deeper questions about what the economy, the public service and the country more broadly should look like. Thinking is moving towards spanning the three scenarios of short, medium and longer term, and how innovation will need to match them.

In addition, the crisis has also caused a re-evaluation of what we thought was important. Pierre spoke about how there’s an opportunity to ask “what is possible now?” For instance, the crisis has removed some of the pre-existing tensions between public and private provision of healthcare – the important question now was what could work best? Asking these deeper questions allows you to rethink and reimagine as you worth through the crisis.

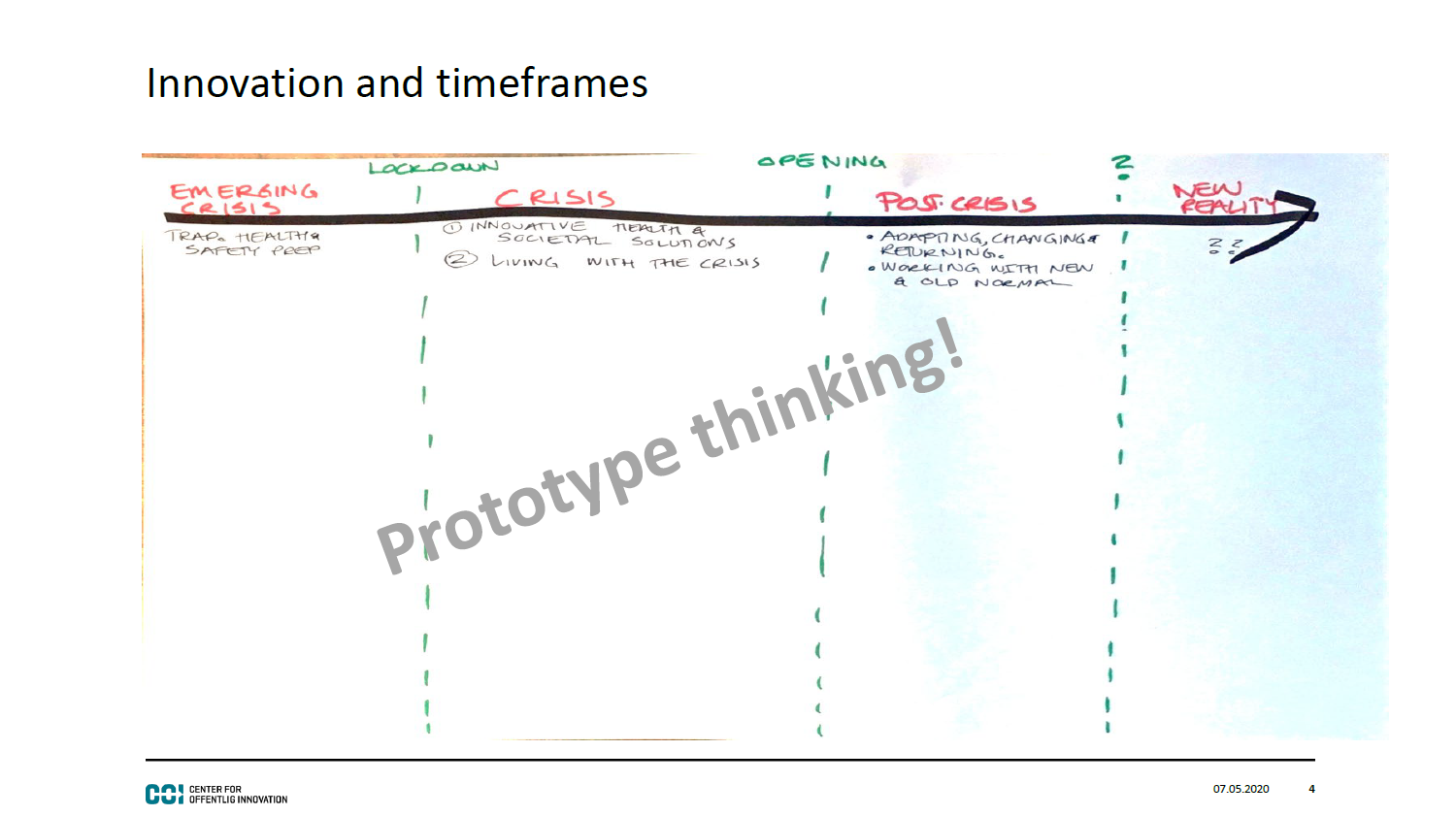

Lene started by reflecting upon a decentralised approach to government, and thinking across four phases – the emerging crisis, the crisis, post-crisis, and the new reality.

Lene spoke about the shifts in thinking that come with each stage, including the surprises of the emerging crisis as things shifted so quickly, and the gradual habituation that came as the crisis has stretched out and it becomes everyday living. She proposed that such a model could be used to help structure conversations with front-line staff and innovation teams to understand what happened and what was learnt at each stage, drawing on a mix of qualitative and quantitative data as evidence. Lene advocated for us to start playing with different scenarios, and to consider what signifies moving between post-crisis and a new reality as we go forward.

Bruno spoke about mapping some of the things that are “right now, not right”, as people have been hijacked by urgency, when they need to fast-track solutions and provide very quick answers. This urgency can provide tunnel thinking, concentrating on the immediate or closed view of the problem, without regard to the broader context or implications. However, other crises are still ongoing even while the pandemic plays out, and there is a need to simultaneously think about those. Somehow governments need to find a way to keep the ability to delivery quickly, but also expand their horizons.

Bruno also warned of the “nostalgia of normality”, when in actual fact we were already trying to change that normal before the crisis. We don’t want to return to the normal as we knew it. We need to build a new normal, not because of the crisis, but because the crisis makes more urgent than ever that the new normal is something different and better.

There is also the risk of scaremongering and blame games, which can make it hard for rational discussion to take place, when the pandemic has demonstrated that wishful thinking and magical reasoning are not going to work. Bruno also discussed how it is important to recognise that expertise leads to necessary medical and technological solutions, but that expertise is not a substitute for public debate. There needs to be citizen engagement, to ensure there is consideration of the diversity of points of view.

Bruno then discussed the importance for the public sector to think about different ways of “futurising”, and thinking about what comes next, including building up the necessary data and evidence and engaging with and re-investing in the innovation eco-system. There needs to be consideration of not just solutions, but their sustainability and inclusivity. There needs to be more use of foresight and anticipatory innovation approaches, and the use of experimentation – test, learn, improve. Even in a crisis, when the pressure is on to deliver, an experimental approach can provide value and help avoid costly errors.

The audience’s answer to a poll about the types of innovation they were seeing revealed a concentration in adaptive innovations, but the discussion with the panellists highlighted the need for governments to be considering their overall portfolio and investing in the other different types of innovation activity as well.

Discussion

The discussion following covered a range of topics, including:

- The fact that, as a system, the public sector will naturally try to return to the default, so it is important to consider the tipping points and how to push things into a new state of affairs. Two levers for doing so that were identified were 1) the fact that the crisis had provided an opportunity to re-evaluate things using values to inform our approach to the system, rather than the status quo; and 2) that the crisis has put a spotlight on government and given it a chance to move more from a command and control approach to one working more in partnership with other parts of the system.

- How the timing is good to start having the conversations about the changes that might be needed longer-term. Some positive signs can be seen from leaders who are being upfront with their staff that things are not going back to the way they used to be. Another approach that offers promise in ensuring there isn’t backsliding on the changes from the crisis is that of involving the users more, hearing and incorporating their perspectives. However part of the answer simply comes down to making it legitimate to have these discussions about what needs to change.

- That it may actually be hard to return to the old normal in some ways, because the crisis has been a training ground, a laboratory for trying new things and improving and customising solutions. It has acted as both a catalyst and an acceleration of a paradigm shift. Nonetheless, it should be recognised that the changes that have occurred did not come out of nowhere – they have built upon the previous gradual accumulation of small changes. Future big changes will also depend upon the continuation of this accumulation and sharing of small changes.

- How the crisis has visibly demonstrated why the previous practice of innovation was important, even if at the time we might not have seen immediate results. We needed to innovate beforehand, so we would be ready for when we absolutely needed to.

- That the crisis has also reminded us of what can be done when there is “collective resonance”, when people are given the opportunity and reason to engage – how can this be made more regular (outside of a crisis)?

- That we need to keep investing in the ability of individuals to be able to innovate, and look at how to create an institutional environment more open to and forgiving of innovation. The crisis has introduced parity for innovation against existing solutions, but we still need a broader conversation about institutional capability (suitability) to take advantage of that.

Panellists were asked to conclude their remarks by noting one thing that the crisis had taught them or emphasised for them about public sector innovation.

Lene suggested that we’re looking at a really interesting time to come, and that this is a one-time opportunity to change things. However, it will be important to balance three perspectives as we venture forth in this new reality:

- Those who want to return to how things were

- Those who want to keep some of the things they have done during the crisis

- And those who see it as a window of opportunity to change everything.

Bruno shared that he thought that public administrations have shown extraordinary capability for adapting and providing answers to unprecedented challenges, but that the work is not yet finished – there will be further challenges to come out of the crisis that are waiting for solutions, such as unemployment, but also the opportunity to strive for big changes for better outcomes.

Pierre concluded by noting that he did not think there will be a new normal, and that he foresaw there being less innovation theatre going forward, and more dirty hands as people actually put into practice how to innovate to respond to all sorts of crises, especially climate change.

The consensus from our panellists was the need to use this opportunity to push for real change, recognising that what we had before the crisis was not all that it could be or needed to be.

Opportunities for getting your hands dirty

The webinar finished with noting three opportunities for people to start getting their hands dirty with innovation as recommended by Pierre. These three things are:

- People are encouraged to submit innovative responses from their own jurisdictions in the innovative responses tracker, to help inform research but also to help countries learn from each other

- To sign up to the next two scheduled OPSI webinars:

- To sign up to be part of the co-design process, to be a potential host, or just to updates of the planned global conversation taking place in November – “Government After Shock”.

We at OPSI give a deep thanks to our panellists and hope that those who participated found it worthwhile. If there are any topics or issues that you think we should explore in future webinars or events, please let us know.