The Future is Unwritten: Persuasive technology in developing countries

Fast forward and imagine the year 2035. For almost three decades, social media – also known as ‘persuasive technology’ – platforms, in that they attempt to influence users’ attitudes and behaviours, have dominated global markets. But now, the fall of established tech giants is in full swing.

In this hypothetical near future, people and governments around the world demanded change after experiencing the negative effects of persuasive technologies. In this new world, governments in low- and middle-income countries support digital pioneers to test and scale business models and digital platforms which are instead designed to advance human well-being and social cohesion. Development organisations play a crucial role in bringing together regulators, policy makers, technologists, designers, entrepreneurs and others across the Global North and South to gather evidence of the effects of persuasive technologies on individuals, societies, regulation and markets.

This is a plausible, if not yet a probable, scenario. Dominance of the technology industry by a select few players currently monopolises much thinking. However, the global social media platform market is indeed starting to shift. Critically, in the Global South where we see relatively low numbers of users but high rates of social media user growth in many countries, national governments and development organisations have an opportunity to shape how these markets evolve – an opportunity that, if ignored, may serve to exacerbate existing inequalities and socio-economic predicaments.

This then begs the questions: what are the hidden risks of large-scale diffusion and use of social media platforms globally, and particularly in countries in the Global South? What are the options for development co-operation in the context of social media platforms? And are there opportunities to learn from the field of collective intelligence to shape the future of social media platforms?

What’s lurking in the shadows

Over the last few years, media investigations, commentators and popular culture, such as the Netflix docudrama, The Social Dilemma, introduced mainstream audiences to the concept of persuasive tech – digital tools with specific features that allow content to be tailored to individual users to influence attitude and drive behaviour-change. Today’s business models of most social media sites rely on maximising scroll time through highly personalized content based on the commodification of user data.

Facebook, for example, collects a gigantic amount of user-generated data and generates recommendations by analysing these data through artificial intelligence. Bulk data sold to third parties can be used to determine religious beliefs, sexual orientation, political leanings and ethnicity, among other attributes. In addition, the platform uses algorithms – gatekeepers of the content users see – to keep users on the app for as long as possible. It shows users content induced from their alleged preferences, thereby reinforcing existing belief systems. Similar mechanisms are at play on other platforms such as YouTube and TikTok.

The negative effects of the use of social media platforms are increasingly being acknowledged and discussed by policy makers on many scales: from its effects on individuals’ mental health to amplifying misconceptions and increasing societal polarisation. However, much more research needs to be done, especially on the effects of social media use on individual and social development dynamics in low- and middle-income countries, where user bases are growing rapidly.

Collective intelligence – a rising sun?

There is immense potential to harness digital technologies, including persuasive technologies, for social good, and the field of digital collective intelligence can provide inspiration and models. Collective intelligence describes the learning, decision-making, sense-making and problem-solving capabilities of social groups and societies in general. To date, only very few governments have leveraged the opportunities of digital technologies to foster collective problem-solving and strengthen social cohesion. However, there are design principles put in practice in collective intelligence systems today that can inform how social media platforms of the future could look like.

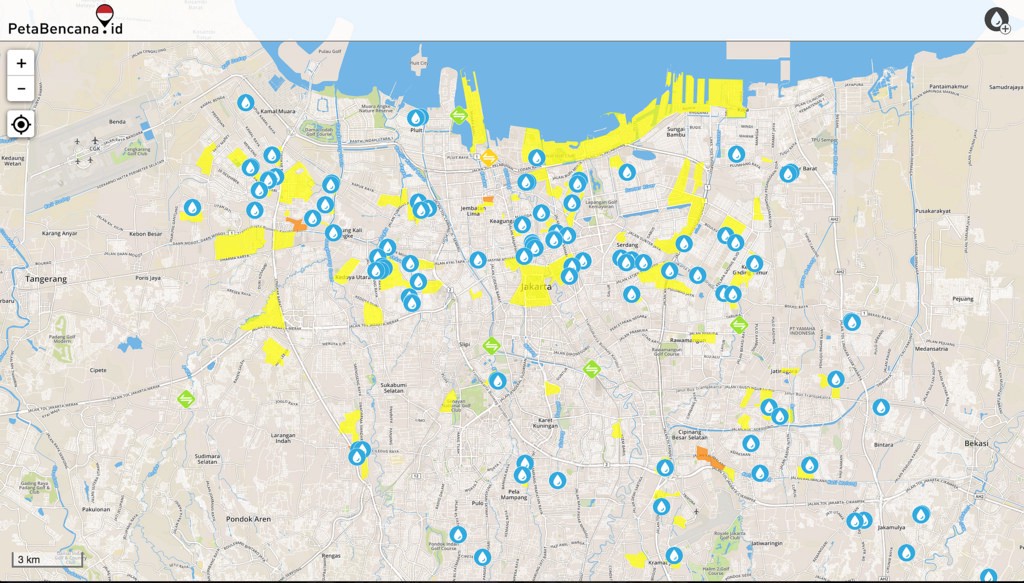

Development providers can make an important contribution by promoting collaborative approaches to identifying good emerging practices and socialising these. Collective intelligence emerges when contributions of individuals combine to become more than the sum of the parts. A great example of this is PetaBencana.

PetaBencana

PetaBencana, Indonesia’s alert system for flooding and other hazards, allows the country’s 17.55 million Twitter users to contribute to the platform to share updates on emerging disasters such as earthquakes, forest fires, smog, strong winds and volcanic activity. Authorities now use PetaBencana to identify where emergency support is needed in real time.

???????? Indonesia

Futures are created

While the impacts of a technology cannot be predicted until the technology is developed and widely used, it is difficult to introduce control or change once the technology is entrenched in a society or economic system – this is known as the Collingridge dilemma.

Therefore, while most dominant social media technology companies seem entrenched, the growth in social media use in the Global South presents an opportunity for development organisations and governments in low- and middle-income countries to take a stance. Investment in mutual learning and co-operation could focus on two distinct aspects of digital development:

- regulating emerging digital technologies, especially persuasive technologies, without stifling innovation; and

- supporting local entrepreneurs to design, test and scale social media platforms and underlying business models that deliberately mitigate the negative effects of persuasive technology platforms and serve local needs and interests.

Furthermore, development organisations should support low- and middle-income countries to gain a seat at international regulation and market-shaping forums and encourage them to play a greater role in investing in dedicated state capacities. Importantly, they can connect partners from the Global South to relevant innovation networks and exchanges to test and scale platforms and business models, regulation of persuasive and other technologies and strengthening digital skills among citizens. To this end, the OECD’s Recommendation on Agile Regulatory Governance to Harness Innovation (2021) could provide guidance and unlock the potential of technology and innovation while safeguarding public interest.

The way forward: Five options for development co-operation

Technologists, regulators and government officials across countries face similar challenges regarding how to contend with the influence of persuasive technologies and social media platforms. The challenges are daunting for any single government. Development co-operation providers can play a role to facilitate collective approaches:

- Focus on technology capabilities overall. Players from low- and middle-income countries face multiple disadvantages in building digital tools that benefit people and societies. Regulatory capacities are low, funding is scarce, and populations require support to strengthen digital skills. Development co-operation actors should continue to work with partner governments on issues related to digital infrastructure, digital skills and regulation.

- Insist that low- and middle-income countries have input. All too often, knowledge exchange on tech regulation and on shaping digital markets happens across high- and middle-income countries, with insufficient inclusion of partners from the Global South. Efforts to regulate technology must reflect the emergent landscape of persuasive technologies and collective intelligence systems as well as Global South perspectives. Development organisations can enhance the scope of what is done today by enabling collaboration and mutual learning between partners, notably governments, technologists and academia from low-, middle- and high-income countries alike.

- Gather intelligence on the impacts of persuasive tech. More research, evidence, insights and learning are needed about the positive and negative potential of persuasive technology in different country contexts. It is also needed across development fields such as education, health, climate change, gender equality and others. Development actors can promote learning by investing in Global South research institutions, cross-country research, and the design of programmes that generate evidence to understand the impact of dominant and emerging tech platform business models.

- Transform learning into action. Development actors can shape markets by using evidence and lessons about the actual or potential impacts of persuasive technology. They can orient technology to the service of local needs and interests by investing in incubators and accelerators that help local entrepreneurs design, test and scale social media platforms and business models that deliberately design persuasive technology platforms for more socially positive outcomes or reframing.

- Invest in systems that serve the public interest. Development organisations can invest in efforts to advance the use of collective intelligence systems in low- and middle-income countries to facilitate more inclusive and participatory decision-making processes and to solve challenges identified by local communities.

Join us on 8 April at 14:00 CET for the OECD High-Level Event: Shaping a just digital transformation. The event will serve as the launch of the new OECD Development Co-Operation Report 2021: Shaping a Just Digital Transformation, which set out to understand how the digital transformation is revolutionising economies and societies, while low- and middle-income countries are struggling to gain a foothold in the global digital economy in the face of limited digital capacity. This blog is based on the chapter Reshaping social media: From persuasive technology to collective intelligence in the 2021 Development Cooperation Report, written by Angela Hanson and Benjamin Kumpf.