Artificial intelligence in the public sector: An engine for innovation in government … if we get it right!

On 22 June, I had the privilege of participating in the conference “Artificial Intelligence: What’s in it for the Public Sector?”, organised in Brussels by the European Commission, the Interoperability Unit of DG DIGIT and the Joint Research Centre. It brought together policymakers and experts to discuss the opportunities that artificial intelligence (AI) brings to accelerate governments’ digital transformation and improve the design and delivery of public services.

The event was a great opportunity for me to reflect back on the work on AI in the public sector that I led at CAF, as well as the work being done by my new team at the OECD, which has been breaking new ground on this subject since the 2019 when it released two pioneering reports Hello, World: Artificial Intelligence and its use in the public sector and The State of the art in the use of emerging technologies in the public sector. It was also a pleasure to discuss this topic with my follow panellists Hilde Hardeman and María Pérez Naranjo, along with our moderator Sven Schade.

The current debate on AI tends to focus on its potential for the digital economy, the importance of regulation that is fit-for-purpose, and the role of governments as regulators. Indeed, governments play a key role in making AI work for innovation, growth, and public value. It is common to think primarily of their role as conveners, building agreement around strategic directions and commitments to foster AI; financiers, providing funding to support research, development and adoption, including through investment funds in AI-driven start-ups; or regulators, ensuring policy coherence nationally with underlying values of society and internationally through regulatory co-operation. However, governments are also prime users of AI to improve the functioning of the machinery of government and the delivery of public service. The focus of our work in the OECD public governance directorate is precisely on the role of governments as direct users and service provider of AI, where governments can and are unleashing many benefits, not just for the internal business of government, but for society as a whole. That is, how AI is a game changer for governments, likely to reset them.

As users, governments are increasingly incorporating AI into their arsenal of tools to improve efficiency, through the automation of physical and digital tasks; to increase effectiveness by being able to take better policy decisions and deliver better outcomes, thanks to improved predictive capabilities; and to increase responsiveness to user needs, delivering personalised and human-centred services through the design of human-centric interfaces.

Leveraging AI as tool for better policies, services and decisions requires governments to think strategically, get the balance right between opportunities and risks and think outside the public sector box to innovate and collaborate with new players.

As I touched on in my remark at the panel, there are a few issues in particular that I believe rise to the top for promoting the effective, responsible and ethical use of AI in the public sector.

Think Strategically: Governance matters

Ad-hoc experiments and initiatives can be great sources of learning, but governments need to have a strategy in place for AI specifically designed for and adapted to the public sector to ensure efforts are scalable. As identified by the OECD.AI Policy Observatory, more than 60 countries have already created a national AI strategy. Importantly, most of these include a dedicated strategy focused on public sector transformation.

However, not all strategies are created equal. Some are more like a list of principles or a checklist of projects. To really drive AI in the public sector, they need to be actionable. As discussed in the recent OECD-CAF report on The Strategic and Responsible Use of AI in the Public Sector of LAC, Colombia’s strategy for AI in the public sector is a great example of an actionable strategy driven form the very centre of government. It’s one of a few that includes all the elements for systemic exploration, adoption, and evaluation of AI. It specifically lays out:

- Objectives and specific actions.

- Measurable goals.

- Responsible actors.

- Time frames.

- Funding mechanisms.

- Monitoring instruments (a rarity in AI strategies).

Having these items in place helps to ensure sustainability and follow-through on commitments and pledges, one of the main challenges we have seen with AI in the public sector. This, of course, will need to go in hand with strong and vocal leadership so that AI in the public sector gains traction. This could take the form in committed leaders making it a priority, but also through new institutional configurations in charge of AI coordination. For example, Spain created a Secretary of State for Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence and the UAE created a Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence. Governing AI is also about making sure that it works for society and democracy. Getting the right balance between its risks and benefits will mean putting citizens at the centre and ensuring that underlying data is inclusive and representative of the society to avoid bias and exclusion. It will also mean setting actionable standards that are fit-for-purpose for the public sector to implement the high-level policy principles being adopted by governments. The OECD AI Principles and the OECD Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector are two key tools to accompany governments in such efforts. These aspects should be built into the design of public sector strategies from the onset, and they should be leveraged to inform the decisions of leaders and practitioners alike.

Accountability: Bring in the auditors and work together on new accountability structures

As underscored in the OECD AI Principles and, more recently, UNESCO recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence, accountability is a critical element for the responsible use of AI in the public sector. While often compared to AI’s use in the private sector, governments face a higher bar in terms of transparency and accountability. Government adoption of AI grows rapidly, as does the public sector’s needs to ensure it is being used in a responsible, trustworthy, and ethical manner.

Key to achieving this within governments are actors in the accountability ecosystem, including ombudspersons, national auditing institutions, internal auditors within organisations, policy-making bodies that establish rules and line agencies that design and implement AI systems. Often, these different groups have had an uneasy relationship, with limited collaboration, often as part of a broader debate on the right balance between innovation and regulation. However, emerging technologies and governance methods, as well as the increasing wealth of available data, are resulting in a re-thinking about traditional public accountability and the roles of these actors.

Within the OECD Public Governance Directorate (GOV), we believe that tremendous potential can be unlocked by forging new paths to collaboration and experimentation within the accountability ecosystem, with all actors working together to achieve the collective goal of accountable AI in the public sector.

While there are numerous areas begging for an injection of innovation in how oversight is carried out, one of the most important policy arena governments are seeking to achieve this is through algorithmic accountability. There is intense debate on how to ensure that the development and deployment of algorithms in the public sector are transparent and accountable. This concern is central to the EU’s AI Act currently under discussion.

Ensuring that those that build, procure and use algorithms are eventually answerable for their impacts.

Algorithmic accountability, as defined by the Ada Lovelace Institute, AI Now Institute, and Open Government Partnership.

Some examples already show the progress on the matter:

- The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities.

- Spain is creating an independent Artificial Intelligence Supervision Agency.

- The UK has issued one of the world’s first national algorithmic transparency standards.

- Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision Making requires that agencies using any system that may yield automated decisions to complete an Algorithmic Impact Assessment in the form of a questionnaire that calculates a risk score the prescribes what actions must be taken.

- The Netherlands Court of Auditors (NCA) developed an audit framework for assessing whether algorithms meet quality criteria. The government, on its side, also developed the Fundamental Rights and Algorithms Impact Assessment tool.

However, it’s clear that more efforts are needed in this area. For instance, through applying its framework, The Netherlands Court of Auditors found that 6 out of 9 audited algorithms did not meet basic requirements, exposing the government to major security and bias risks.

Taking action in this area is crucial for ensuring the long-term viability and legitimacy of AI in the public sector. Without this, governments will lack citizen trust and open themselves to major risks when problems with algorithms are uncovered. The OECD is currently exploring work on promoting collaboration among ecosystem actors in pursuit of algorithmic accountability and we are seeking collaboration opportunities with others who are interested (please feel free to get in touch).

Strengthening Capacities with the Three Ps: People, partnerships procurement

For AI to work successfully in the public sector, I believe, and our work at the OECD has shown, that there are “three Ps” that are fundamental for governments in their pursuit of AI: People, partnerships and procurement.

People

First, governments need to invest in people and enhance their internal capacities, particularly the skills of public servants. Artificial intelligence is meaningless without human intelligence to get it right.

A foundational precondition to innovate with AI is understanding its potential uses in the public sector, as well as the potential implications and trade-offs. The OECD Framework for digital talent and skills in the public sector underscore this central challenge for many governments in the digital era. Not everyone should become an expert on AI, but understanding its potential is critical. For example, Finland’s Elements of AI free and open course helps both citizens and public servants gain a solid understanding of AI.

Our Digital Talent and Skills Framework also recognises formal training as a key element to continuously upgrade digital skills in the public sector. In Argentina, for instance, the Artificial Intelligence Multidisciplinary Training Programme provides training tracks for full-stack programmers, data leads and AI project managers and programmers.

Partners

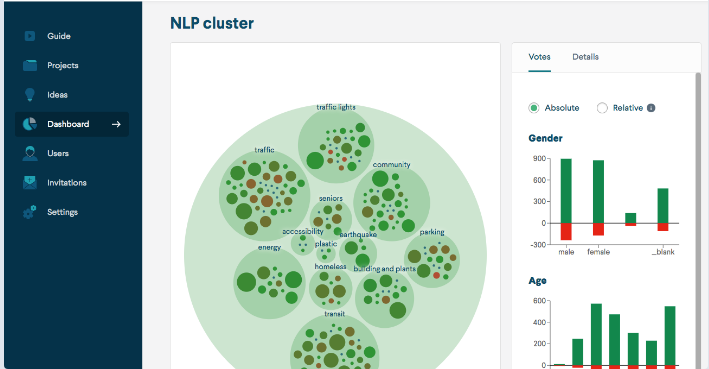

Second, governments also need to strengthen their capacity to collaborate with external partners, such as govtech and civic-tech start-ups, that can facilitate the absorption of digital innovations in governments, especially ta the local level in cities. Such partnerships can yield new ways of solving problems. For example, CitizenLab, a Belgian govtech start-up, uses AI to automatically classify and analyse thousands of contributions collected on citizen participation platforms. Civil servants are then able to easily identify citizen’s priorities and make decisions accordingly.

Collaboration and partnering can take various forms. Challenges and prizes are one way to kick-start collaboration with civil society and academic institutions. But more formalised and systematic collaborations, such as cross-sector partnerships, can tap into new abilities and expertise in leading-edge practices. Chile’s Data Observatory (DO) and UK’s Public Policy Programme at The Alan Turing Institute are among the most successful collaboration experiences in AI for the public sector.

Procurement

Third, effective AI procurement is vital; it is a central policy tool governments can deploy to catalyse innovation and influence the development of solutions aligned with government policy and society’s underlying values.

Civil servants will need to learn new procurement practices and approaches. For instance, Chile’s Public Procurement Innovation Directive helps public servants leverage more innovative approaches to public procurement, and meet the needs and demands for new products and technologies. Sometimes simply clarifying existing rules can go a long way. The TechFAR Handbook in the United States highlights flexibilities in the country’s 2,000+ page procurement regulations that allow agencies to work with start-ups and conduct iterative, user-driven service development.

We also need more focused efforts to facilitate greater cooperation between government entities and govtech start-ups to foster digital innovation, improve service delivery and diversify tech providers. Some efforts are already demonstrating this potential. For example, the GovTech Leaders Alliance is a group of national and city governments committed to promoting common principles for govtech strategies around the globe and sharing lessons learned, propelled by the government of Colombia and propelled by the Development Bank of Latin America, CAF. Governments can also engage directly in govtech development, incubating and accelerating govtech solutions within government agencies. Through Start-Up Brazil the Brazilian government itself accelerates and funds start-ups that can provide solutions across sector, while also promoting economic development.

A better and consistent way to achieve better AI procurement would be thinking of it strategically, such as building national strategies on govtech. The UK’s Government Technology Innovation Strategy is a leading example, covering dimensions of people, processes, data and technology to catalyse govtech efforts, including AI.

The main limitation in building partnerships and better AI procurement, especially with govtech start-ups, is that the external expertise needs to be matched with the internal expertise. Public servants and leaders need the right skills to be able to collaborate and engage with external partners. Having the right balance on the three P’s will help governments building trusting, collaborative, and strategic relationships to achieve public value.

The Digital, Innovative, and Open Government Division at the OECD is working to incorporate govtech as part of its main areas of work, recognising this tremendous potential for bringing together govtech start-ups and government, in particular city governments, as one of the biggest enablers of AI in the public sector. For this reason, the OECD and CAF will be releasing a Digital Government Review of LAC later this year with a dedicated discussion on govtech.

While we find that these are some of the top issues for AI in the public sector, they are, of course, not the only important aspects. Governments also need to consider topics such as experimentation, data leadership and strategy, funding, and digital infrastructure, among others. In-depth details on each of these can be found in our reports on AI in the public sector in general, and in Latin American more specifically, as well the OECD AI Policy Observatory and the OECD AI Principles. Going forward, we will continue working with governments around the world to both learn from their successes and challenges and to support them in driving this area forward in an informed and trustworthy manner. Does your organisation work in this space and want to collaborate? Get in touch with us at [email protected].