Zone of confusion: The need for a clear purpose for innovation projects

Have you ever felt pulled in different directions at once, such that you do not feel like you are really making headway? Or that when trying to do multiple things at once, you end up not doing any of them well? In this post I’d like to explore what happens when innovation projects try to cater to multiple purposes at once.

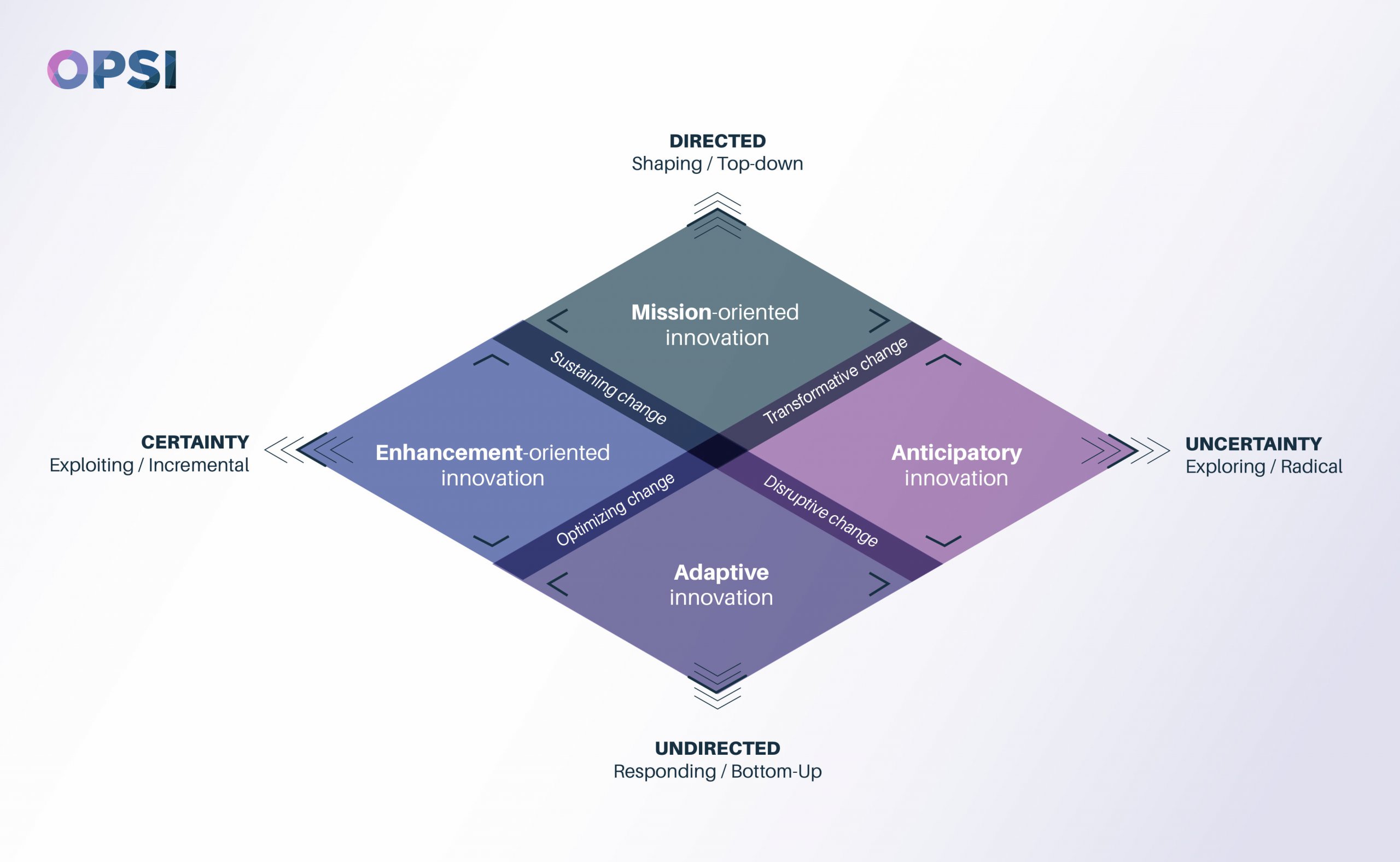

In a previous post we have discussed how when activity overlaps in different innovation facets that it can contribute or lean towards a particular type of change:

- Sustaining changes: Enhancement-oriented and mission-oriented innovation combined contributes to sustaining changes, activity that is likely to work towards sustaining and extending existing business models, operating practices, and paradigms.

- Optimising changes: Enhancement-oriented and adaptive innovation combined contributes to activity that is likely to work towards optimising changes, those that are optimised for the environment and intended to deliver efficiency/effectiveness gains, building on ongoing learning about what works and what doesn’t, and when.

- Transformative changes: Mission-oriented and anticipatory innovation combined contributes to activity that is likely to work towards transformative changes, changes that overhaul how things have operated, but in a way that is in line with the mission/political priorities of the day.

- Disruptive changes: Adaptive and anticipatory innovation combined contributes to disruptive changes, changes that may well have emerged in response to a changing environment/changing technologies but due to their origin from a bottom-up source (e.g. front-line staff, partners or stakeholders), they will challenge existing models and strategies, and may therefore be resisted or pushed-back against.

In some of the workshops we have run with countries and some of the conversations we have had with practitioners about their portfolios of innovation activity, there has been a tendency to sometimes put innovation projects to the centre of the facets model. This is a very natural tendency – if something is not clearly one thing or another, or if there’s disagreement or uncertainty about the underlying intent of a project or support measure, then why not put it in the middle, where it might touch on all of the different facets of innovation activity?

A faceted approach is a nuanced approach

The facets model is underpinned by two different tensions:

- The extent to which there is a clear directionality or known outcome or objective that is wanted (even if the how of achieving it is unknown)

- The extent to which there is more or less uncertainty governing the activity at hand.

Each ends of these spectra are separate from each other. And the facets model reflects this rather than a traditional (2×2) model.

To illustrate, let us take the example of a hypothetical ‘green new deal’, of which a number of countries are starting to talk about and introduce. If there is a clear and explicit mission (e.g. zero new emissions by 2035), then this automatically means that it is in tension with pure enhancement-oriented innovation. Enhancement, building on existing things even with new approaches, is going to be too incremental (i.e. a linear projection or extension from the status quo will not deliver upon it, therefore meaning some fundamental elements will need to be questioned or revisited). Anticipatory innovation will also be in tension, because there is a clear definitive goal, presupposing that any new developments will be subordinate to this goal (What if technological gains could bring it forward? What if new technologies could neutralise carbon emissions, thereby reducing the need for change?). And of course, adaptive innovation will also be in tension (How will this goal fit with the actions of millions of households? How will the top level goal allow for nuance and difference between different sectors and segments while also maintaining legitimacy and fairness? What if some sectors require special treatment, requiring others to have to achieve more than others?).

Of course, in reality, there is never true purity. Nuance, subtleties and complexity govern our lives, and thus should be reflected in our models and structures for understanding the world. Absolutes rarely lead to public sector success. Thus we recognise that many innovation projects will fit in-between or sort of ‘lean’ in particular directions while also having nuances of others. The facets model is simply intended to help make more explicit the underlying intent behind innovative activity, and to appreciate the different forms of support and considerations that will affect or help shape its success (or not).

Simultaneously serving more than one master

However, something that is important to be clear about is that innovation projects that try and address multiple aims at once become dramatically more complicated and complex very quickly. Ensuring activity helps both a mission-oriented approach but also is anticipatory is going to be challenging, because you need to have both a big audacious goal while simultaneously also questioning some fairly fundamental things and suspending fixed notions not only about what the future might be, but what it should be. Engaging in enhancement-oriented innovation activity while simultaneously being open to adaptive innovation can be difficult, because you need to both be set upon improving what is and be open to feedback and questioning about how things work and why.

Each of these intersections can of course happen, and I am sure there are projects everyone knows that highlight this – e.g. business process improvement can also be aided when you are open to feedback from staff and clients about their actual needs. However, this is also rarely easy.

There may also be projects that you think of that fit across three parallel facets (e.g. you could have a climate change plan that sets high level targets, invests heavily in emerging technologies and business models, as well as introducing enhancement-oriented innovations such as minor home renovations or business energy reduction plans). Again, however, this adds to the complexity, whether it is being delivered across multiple organisations or from different parts within one organisation. There are inevitably going to be certain points of conflict and tension. For the ease of illustration I have chosen a very ‘big’ example, but the complexity will still remain as you shrink a project down.

Finally, what happens if activity attempts to span all four facets simultaneously?

Well, trying to both cater to high uncertainty and relatively less uncertainty, and working towards a high level ambitious goal while also being open to a wide range of other ideas is often going to be messy. You cannot do all things at the same time, and expect for it to be successful.

Thus, we suggest that at the heart of the facets diamond is a zone of confusion. If a project or activity is considered as best fitting against the centre of the diamond, it is likely trying to address everything or it is still emergent and the intent has not yet become clear.

This is not fatal, and some projects will take time to evolve and work out what its real aim or intent is. However, if the activity stays within the centre, without ever being more distinct in its relation to the different facets, then it is a warning sign – it is a project where the intent is not clear (never a good sign), it is a project trying to address too many competing expectations and demands (also not a good sign), or it is really going to do all the things (in which case the organisation’s management should be concerned because they’ve either got some masterminds attempting the impossible and/or they do not really understand what they have signed on to).

In short, each facet has been described and identified as discrete because each is different and involves different forms of support, different tools, different skills (or manifestations of those skills) and different mindsets. Attempting all at once within the perspective of a single activity or project lens, is going to be incredibly complex. And while there are no doubt some very capable people out there who are adepts who can draw upon the strengths of the different facets at once, the chances that they simultaneously work with enough other people who can also do likewise and are supported by an organisation with the proficiency to manage such a multi-headed beast are pretty slim. The bigger the scale and the more the need for a diversity of approaches and forms of support, the more that the tensions between the different facets are likely to appear. As these tensions increase, the more that the required capability demands will rise, as more people are needed who are also comfortable in managing the competing tensions between the different facets.

A multi-phased approach over a multi-purpose approach

This is not to say that there are not many innovation projects whose focus will move or change over time. For instance, at the start of a government’s term, there may well be a big audacious goal that will be best supported by a mission-oriented approach to innovation, with big challenges that can be worked towards. However, the nature of the political process being what it is, it is likely that towards the end of a government’s term, the focus on the big audacious goal may have transformed somewhat, and involve more adaptive innovation focus (How does this translate on the ground, how do we make sure that it fits with and adapts to people’s needs?) and/or a more enhancement-oriented focus (How do we make sure this is integrated into our operations and speed up delivery and results?).

The key distinction is that in such instances the dominant facet for the innovation activity will change, and thus so will the associated forms of support. Our Facets Workshop for instance, has some of the ‘plays’ that might mean a project will change course (or could even be used to push a project into another facet).

Again though, the innovation facets model is not prescriptive nor a recipe book. Innovation, by its nature, is inherently contextual and thus there will always be subtleties specific to specific contexts. Rather it is intended to act as a prompt and a resource for making explicit things that can all too easily be left as implicit assumptions, which will is a recipe for a difficult job.

A chance to test your innovation portfolio in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated crisis

To help make the innovation facets framework a bit more ‘real’ and usable to different organisational contexts, the team, as part of our H2020 work has been developing an online tool to help you reflect upon the innovation tendencies of your team or organisation, and its innovation portfolio stewardship. This tool has been developed building upon the framework as well as our experiences in using it with different jurisdictions.

As part of the lead-up to Government After Shock, teams can test out the tool and reflect upon what their innovation portfolio tendencies, stewardship and project portfolio suggests and whether it aligns with what might be needed or learnt in light of the crisis. More details will be released soon, you can sign-up if you would like to take part and then there will also be a session as part of Government After Shock where different teams will be able to share and discuss their results.

Feedback

As always, constructive comments and feedback are important for us in improving our thinking and the resources that we provide for governments and practitioners in taking a more deliberate, consistent and systemic approach to innovation. Please get in contact with us, connect with us on Twitter or through our LinkedIn presence, or get involved and join in with Government After Shock.