Foresight Fast and Slow: Anticipation as a force for democracy in our times

Back when I was an exchange student in France, I lived in an apartment shared by nine people, all from different countries and cultures. We had a large kitchen and lived on the city’s main square, so it was a prime location to host some of the best house parties. Imagine: nine people each bring a dozen friends and you’ve easily got over a hundred people in your home!

One of the things that most intrigued me about these parties was the time at which people showed up. There would be those who arrived promptly at the precise time stated on the invitation; those who came along within an hour or so; those who joined when the party was already in full swing; and those who got there just as we were starting to clean up and go to bed.

What these unsynchronised gatherings highlight to me is the fact that there is flexibility in how we experience time and plan ahead. It is a well established fact that time passes at different rates for different observers, that there is no universal present shared by everyone, and that our knowledge of the future is always fragmented and incomplete. We also each experience time differently: neuroscience has found that very busy times seem to pass very quickly, but our memories of them feel slower. The opposite is true for calmer periods when we’re bored.

Our perception of time is also significant for our opinions and actions. A fast rate of change can be destabilising and induce anxiety, leading us to want to apply the brakes or even go back to the way things were. It is often said that people “left behind” by the forces of globalisation are more susceptible to support reactionary populist movements. Slow progress can be frustrating too, and lead to crises and missed opportunities when governments fail to adequately prepare for or respond to big oncoming developments like automation or climate change.

We are all living in a particular place in time, but like the fish that doesn’t know it’s in water, we forget that our experience isn’t universal. Pluralism is an essential ingredient of democracy. So it is a problem whenever policy discourse assumes that our past, present, or future is singular. Recognising our implicit perspectives and making them explicit is a first step towards broader, more inclusive dialogue and collective decisions—and ultimately towards strengthening democracy. The following examples show how time can be distorted in policy, and how a clearer picture would look. Through the process of perceiving, understanding, and acting on emerging future developments—a discipline known as strategic foresight—we can fix these distortions to support better government by and for the people.

Issues are not short- or long-term. Actions are.

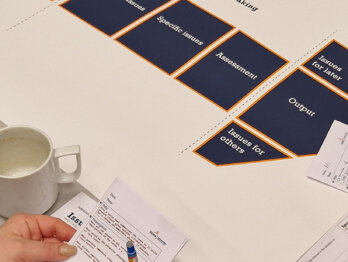

One particularly pernicious example of distorted time is the artificial division of issues into either “long term” or “short term”. This distinction is easily falsified by considering how challenges like the COVID pandemic, international conflict, and migrations affect different people right now and in the future; and how our responses to them will have consequences in the short and long term. The same applies to pressing policy issues that don’t always show up on our radar: intergenerational fairness, by definition, must obligate the generation of today to consider the needs of the generation of tomorrow. Policy discussions should attempt to capture the long-term implications of short-term actions; and the short-term needs of long-term goals.

Policy discussions should attempt to capture the long-term implications of short-term actions; and the short-term needs of long-term goals.

Multiple timelines coexist

When discussing the future, people often try to specify the time horizon. This ex-ante definition of a timeline can be problematic for several reasons. First, there are usually multiple connected factors, each with their own uncertain timelines. The conversation can therefore be easily distracted by guessing the exact speed and timing of events, rather than preparing the necessary policy responses for today. Second, different decisions are considered on different timescales: a forestry commission might make detailed plans hundreds of years ahead, while organising a referendum is much shorter. Third, there is a risk of misinterpreting electoral cycles. It is true that many policy agendas, such as tackling the climate crisis, transcend policy makers’ terms of office. Yet it is also important for democracy that incoming leaders are unconstrained by past decisions, in order for them to honour the will of the public. Policy should therefore learn to work with multiple concurrent timelines and have the capability to speed up or slow down actions in response to changing conditions.

We don’t all start from the same point or go in the same direction

Another distortion of time is the metaphor of the future as a cone, with the present as a single point and linear paths to multiple possible futures, running from left to right. In strategic foresight, we should know better than to assume everyone is starting from the same point and heading in the same direction. Others have debunked the “cone of possibilities” in greater detail for its unsubstantiated topography of the future and its depiction of the journey to the future as a smooth line instead of complex and messy networks of events and shocks. Any discussion of future policy should systematically account for the different backgrounds and needs of those affected.

The future doesn’t already exist: it emerges

Another misconception baked into the cone-depiction of the future is the impression that it comes to us as if on a conveyor belt. We often think of phenomena like populism or trends like ageing—as if they had a life of their own—when really they are the result of a combination of changes that come together in a way that we recognise and put a name to. As we explored in our scenarios on the future of ageing and talent management in public administration, the meaning of a policy issue depends greatly on the context and interacting factors. We often assume that things will continue in the same direction or grow exponentially, like the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubling about every two years (“Moore’s law”). But making real sense of the future requires considering what feedback loops, reactions, mitigating factors, tipping points and counterintuitive consequences might arise. For example, old preconceptions about ageing, whereby older workers are assumed to lack skills or career motivation, may no longer hold—in fact, there is active discussion about how the 50s and beyond are becoming a phase of career acceleration for many, particularly women. Policy discussions shouldn’t just take trends and issues as given: they should question where they come from and whether our judgement of them (good or bad) will be the same five years from now.

Policy discussions shouldn’t just take trends and issues as given: they should question where they come from and whether our judgement of them (good or bad) will be the same five years from now.

Tech is about devices, not destiny

A particular case of misconceptions about the effects of time is in the discourse around tech. Technologies from typewriters to toasters have indeed catalysed great changes. But in the hype about tools, it is easy to forget that they didn’t emerge or develop in isolation from their societies.

It is not sufficient to refer to technological trajectories to understand, for example, how artificial intelligence may enable governments to transform their role and function in society. Likewise, it is not the existence of social media but the way it is set up and the way people use it that determines its role and influence in civic debates. Without that additional analysis and interpretation, studying a technology on its own does not support us to imagine ourselves in a very different future—or develop strategies to succeed in it. Hence, policy should not only consider the evolution of technologies but the societal values and motivations that could harness or respond to those technologies, and the impact on our democracies.

What worked in the past might not work in the future

There’s a lot to be learned from comparisons with other times and places: history helps us avoid the mistakes of the past, and peer exchange helps us emulate others’ success. But future conditions might mean that the best way to achieve certain values might not be the same. For example, many cities in the past undertook extensive highway-building projects to help people get around, but in recent years have come to prefer greater bike and pedestrian infrastructure as ways to improve quality of life. Likewise, we believe in fundamental principles of democracy such as equality, trust, and integrity; but the way to achieve them might have to change. This is why work on innovative citizen participation, such as deliberative democracy, is so important.

Figuring out our place in time and what it means is indispensable for taking meaningful action to advance our democracies. OPSI is working closely with governments like Finland and Ireland to boost their capacity to govern with foresight and practice future-fit policy making. To find out more about our work in strategic foresight, see our page on anticipatory innovation.