Futures LIVE

As a devoted fan of the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) for over 20 years, the coronavirus pandemic brought a big disappointment for me in 2020: the cancellation of the most important week of my year. As I had done in Kyiv, Lisbon, and Tel Aviv, I planned to travel to Rotterdam to see the live shows and embrace dear friends from all over the world in this joyful and camp annual extravaganza of music and pizzazz. Instead, for the first time in over 60 years, the event had to be cancelled because of a disruption of unprecedented severity.

For the 2021 edition, organisers vowed that the ESC would go ahead in some form, “no matter what”. Their way to do that involved envisaging a set of scenarios reflecting the circumstances in which the event might have to take place. These were published, along with corresponding response plans, in September 2020. My heart sang. My lives as an ESC fan and as a scenarios practitioner had come together.

In addition to giving clarity to organisers and fans, the 2021 ESC scenarios have also given rise to some interesting anticipatory innovations. For example, for the first time all participating acts will be recorded “live on tape” weeks prior to the actual Contest. The recordings will be used in case lockdowns, quarantines, or travel restrictions make it impossible for performers to appear on stage. It is unclear whether this practice will remain, but it is certainly helpful in 2021 to increase the resilience of the show against the still-ongoing turbulence of the pandemic.

The future of public service media

Keen to support this kind of work, I contacted the organisation that oversees the ESC: the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). The EBU is the world’s leading alliance of public service media (PSM). They have 115 member organisations in 56 countries and have an additional 34 Associates in Asia, Africa, Australasia and the Americas. Members operate nearly 2,000 television, radio and online channels and services, and offer a wealth of content across other platforms. Together they reach an audience of more than one billion people around the world, broadcasting in more than 160 languages.

The EBU’s strategy team immediately showed their understanding and enthusiasm of the value of scenarios for helping to understand and navigate the future of PSM. What is the future of mass media in a world of increasingly intelligent and personalised content recommendations? What needs could arise that streaming platforms are unable to meet? How might geopolitical and cultural shifts change our viewing preferences? What innovations could make fake news a thing of the past? What new habits formed during the coronavirus pandemic could persist for many years?

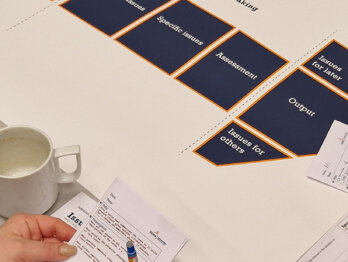

Together with the students I teach on the “Disrupted Futures” programme at EM Lyon Business School, we set about considering these questions and many more. Their task was to conduct strategic foresight: perceiving and making sense of the future developments emerging today in the world of PSM, and envisaging actions that could be taken to better prepare.

Scenarios for public service media

Through a complex and suitably messy process, four scenarios emerged. They are rather more eclectic than those developed for the ESC, which is to be expected for such a broad topic and such a wide range of potential users. But by engaging with the future in this way, the EBU are demonstrating that they are going beyond just trying to predict, plan, and pray when it comes to the future of PSM. They are helping their members to explore, navigate, and act.

The four scenarios are:

- YouChoose: highly individualised, personal media and automatically generated content

- Subsaharan Superstars: talent and tech catalysed by diaspora communities

- Come Together Apart: social movements gathering in virtual reality broadcasts

- Fake Fun: competition for attention and legitimacy, with propaganda dressed as entertainment

A summary of the four scenarios is below. As always, they should not be interpreted as predictions or recommendations; nor do they represent the official position of the EBU, the OECD, or any other organisation or its members. They are fuel for conversation. The intention is that PSM organisations can discuss their strategic decisions with these scenarios in mind in order to enlarge the frame of what they need to take into account; to reveal and challenge their implicit assumptions about the way the world works; and to test how robust they are against potential future disruptions.

There is no specific date on these scenarios, reflecting the fact that they are intentionally fictional. Readers who find it important to pinpoint a year might want to consider 2030, since anything sooner might be too close for the reader to act in time; and anything later might be too distant for the reader to have to act now.

YouChoose

What happens in my show stays in my show

This is a world in which personalised media is about to replace mass media as people’s choice for education, information, and even entertainment. Thanks to AI, algorithms are now able to not only offer the type of content people most want, but actually help create the content too. It started with documentaries and expanded into news shows and even sitcoms. People have stopped gathering around the television or going to the cinema for shared viewing experiences, and instead view media as something very intimate and personal—even private. Questions are arising about whether this new wave of personalisation in media is fuelling a new wave of individualism in wider society.

YouChoose is a world in which brain-computer interfaces combined with AI have made everyone into the director and producer of their own content. Creativity is now so unconstrained that there is no end to what can be imagined. Being a creator can be great fun and very empowering—at least for some. But it can also be exhausting, and many people miss the days when they could just sit in front of something and wind down. Questions are also arising about how good it is for people to only ever be presented with ideas and information that make a profit for the brain-computer interface providers.

Subsaharan Superstars

European elephants struggle to keep up

This is a world in which African content producers are becoming world media superpowers. Helped by access to the latest technology which is much less dependent on old-fashioned infrastructure, and young, dynamic populations, new superstar influencers are attracting worldwide audiences in English, French, Portuguese, and many other languages—including in Europe. It started with diaspora populations and then spread to the rest of the world. Cultural identities and standards of beauty are shifting, transforming debates about diversity and inclusion, as well as the scars left by colonialism and racism. Questions are arising about whether European broadcasters are still in touch with their audiences, and whether they should compete or engage with the world’s new media powerhouses.

Subsaharan Superstars is a world in which new devices, larger than a phone but smaller than a TV are turning the broadcasting industry upside down. Originally successful in the Silicon Savannah of subsaharan Africa, where countries were less burdened by old-fashioned broadcasting infrastructure, these new devices have found a place in most European and North American homes too. Instead of passive watching as individuals, content on these new devices encourages interaction and shared experiences. Questions are arising about how traditional broadcasting organisations like EBU members are dynamic enough to keep up, and whether the content of those broadcasters still suits the new interactive, sharing-friendly formats.

Come Together Apart

Virtual concerts and virtual cuddles

This is a world in which social isolation has reached a point that people have started to reconnect in new and unexpected ways. Prolonged and recurring pandemics have entrenched social distancing into all human cultures. The physical safety of staying at home has made people highly mistrustful of strangers in real life. But thanks to virtual reality, this new world is getting easier to live with. Broadcasting has moved beyond linear transmissions and into the creation of entire virtual spaces and environments for people to access and experience. For example, the Eurovision Song Contest, now held entirely in a virtual arena created by the host broadcaster of the previous year’s winner, frequently sells over 20 million tickets. Thanks to this new broadcasting concept, people are meeting and forming meaningful connections that would never have been possible with traditional television, social media, or even face-to-face communication. Questions are arising about the kind of connections being made, and whether the broadcasters providing virtual social connections have interests other than their users’ well-being.

Come Together Apart is a world of increasing psychological awareness. Lockdowns during the pandemics pushed people to reconnect with their emotional needs and demand action from governments and others to meet those needs. Entire industries around psychology and behavioural insights have flourished—helping individuals with their mental health while also helping broadcasters with their ambitions to create more immersive, emotional, and engaging virtual spaces. Questions are arising about whether governments are supporting those who need it most, or simply those who express themselves loudest.

Fake Fun

Nothing is completely free of politics

This is a world in which large tech firms have gained so much power that they compete with governments for influence over people’s lives. Of course they still have separate roles too, but fierce battles rage over what information people receive about the world and whose perspective counts: firms or governments. In order to reach more people and avoid legislative hurdles, tech giants increasingly use entertainment as a ‘gateway’ or cover to entice consumers. Public service media has become an intensively competitive sphere, in which people’s attention but also their political sympathies are fiercely fought for every day. Questions are arising about whether this rivalry is healthy competition or destructive for society and the planet.

Fake Fun is a world in which fake news has taken on a new meaning. No longer about mass conspiracy theories or attempts to dupe voters, fake news has evolved into a softer, more personable character. The line between entertainment and propaganda has blurred as broadcasters of all kinds compete to win people’s support. Streaming platforms, all offering a broadly similar service at the same price, are forced to appeal to emotion and identity, creating new kinds of tribalism and polarisation. Questions are arising about ethics and media literacy, and whether AI can help people take a more critical view.

Using the scenarios

As always with scenarios, it is the questions they raise which help us learn the most. Which scenario did you find most uncomfortable? Which one would need the biggest change in strategy for organisations? Which one is the most provocative?

The future for public service media is highly uncertain. It is already challenging to build the best broadcasters, but that’s not enough: no strategy is unsinkable, and every organisation must constantly look out for disruptions, danger, and opportunities ahead. Success in the future depends on perceiving, making sense of, and acting upon signs of emerging change now. To help ensure this strategic foresight work is put to use, OPSI has developed a framework of Anticipatory Innovation Governance. For more information, please read our brief.