Governments must judge hundreds of new programmatic budget proposals each fiscal year with little objective information about whether they will achieve the results claimed. Evidence of program effectiveness is a critical data point that is used when making budget and policy decisions, as programs with greater evidentiary support are generally more likely to deliver a high return on investment of public funds. The The Policy Lab at Brown University leveraged existing public clearinghouses of peer reviewed evidence, simple evidence definitions, and updated data collection to provide that clarity. This evidence scale gives State of Rhode Island policy officials quick insight into the level of evidence each proposal contains so better budget decisions can be made.

Innovation Summary

Innovation Overview

Why is this issue important?

If you’ve been near a budget office in the last twenty years, you know the rhetoric. Spend dollars on programs with evidence. Programs that perform. Programs with results. Everyone agrees, but how do you actually do that in the chaotic melee of real-world budgeting? A challenge is that people inside the budget formulation process are both overwhelmed and underwhelmed with information. When preparing the typical Rhode Island budget for the next fiscal year, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) analyzes budget submissions from 55 agencies, including over 500 high-level decision items, in the span of just 16 weeks. Topics vary wildly: financial aid for small businesses; a dockside testing program for shellfish toxins; Medicaid coverage for Doula care; cybersecurity infrastructure; furniture replacement. Details varied wildly too, from pages of technical justification, to almost no justification at all. Unless wide swathes of evidence can be quickly and efficiently distilled into the budget process—at the right time and in the right ways for the right people—then that evidence stands no chance of being absorbed into the process. And when that happens, we may accidentally waste tax dollars.

What did we do?

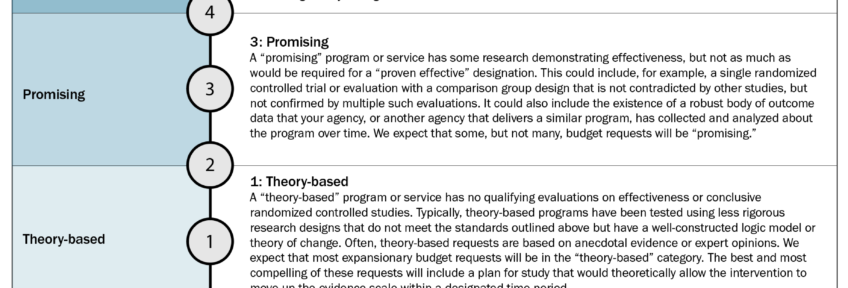

This project begins with the insight that, when it comes to sharing information, the design of everyday paperwork and opportunities to discuss that paperwork matter. Templates can guide users on what information should be included, and templates can set guardrails for how to present that information. We redesigned the form (called a “Decision Package”) that Rhode Island agency staff use to propose new budget items. We trained staff on how to use the template, held daily office hours to help fill it out, and updated Budget Guidance. The design was meant to help users think and communicate more clearly about the evidence behind their proposal. Importantly, we introduced an Evidence Scale (0 to 5) which ranked a proposal in terms of its evidence base – developed from recommendations from the Pew Results First Initiative. Acknowledging that many programs have limited evidence, a series of questions were designed to help identify opportunities to invest in generating evidence. Pew’s Result’s First Clearinghouse and Arnold Ventures’ Social Programs that Work database catalog thousands of program evaluations, and were used by agencies to help determine the level of evidence. A brief view of the Rhode Island scale:

- Proven Effective: A program or service that is “proven effective” has a high level of research on effectiveness. Qualifying evaluations include studies such as randomized controlled trials and evaluations that incorporate strong comparison group designs. These programs have been tried and tested by many jurisdictions, and typically have specified procedures that allow them to be successfully replicated.

- Promising: A “promising” program or service has some research demonstrating effectiveness, but not as much as would be required for a “proven effective” designation. This could include, for example, a single randomized controlled trial or evaluation with a comparison group design that is not contradicted by other studies, but not confirmed by multiple such evaluations.

- Theory-Based: A “theory-based” program or service has no qualifying evaluations on effectiveness or conclusive randomized controlled studies. Typically, theory-based programs have been tested using less rigorous research designs that do not meet the standards outlined above but have a well-constructed logic model or theory of change.

- Evidence of Insufficient Impact: A program has “evidence of insufficient impact” if quality evaluations have measured no meaningful difference in outcomes between program participants and those in a comparison group. A program that regularly fails to reach its outcomes targets also falls into this category.

What happened behind the scenes?

The budget process is fast. Budget analysts occasionally need 24-hour turnarounds on feedback. To facilitate rapid, expert consultations about the evidence behind draft proposals, RI OMB and The Policy Lab entered into a Memorandum of Understanding, which empowered sharing internal documents and giving pro bono assistance.

What have we learned?

Staff welcomed the new template. If nothing else, the instructions and layout were easier to use. This improved flow increased buy-in, which is notable because the form actually demands more information to complete than in previous years. Most importantly, Governor’s staff and OMB leadership report more in-depth budget discussions with solid evidence information available when it is needed.

Innovation Description

What Makes Your Project Innovative?

The Policy Lab at Brown University, the Rhode Island OMB, and the Governor’s Office collaborated to re-design the suite of budget guidance, trainings, and templates with user centered design and the latest thinking on evidence. The Lab systematically collected decision package template(s) in all 50 states that agencies would use to submit their budget requests. The addition of the scale adds a dramatic element of clarity into the viability of the budget request. The scale views evidentiary support on a continuum, from programs that are virtually proven effective to programs that are based on strong theories and expert opinions. Evidence of program effectiveness is a critical data point that is used when making budget and policy decisions, as programs with greater evidentiary support are generally more likely to deliver a high return on investment of public funds. This innovation is only possible because of existence of Evidence Clearinghouses.

What is the current status of your innovation?

We are now on our third budget cycle implementing the revised budget template and evidence scale. The most recent view of the budget instructions can be seen in the Files section, pages 15 to 16. The decision package forms have now been imbedded into a cloud-based budgeting system that allows direct population of the database. The scale has been refined and Pew has transferred management of Results First states to The Policy Lab, National Council of State Legislatures, and Council of State Governments. This effort is renamed the Governing for Results Network (GFRN) where a number of states have implemented a version of the evidence scale to evaluate budget proposals. These states recently gathered to share evidence definition and evidence scale best practices at the GFRN conference.

Innovation Development

Collaborations & Partnerships

- Agency Fiscal Staff – Primarily responsible for providing the budget requests.

- Agency Program Staff – Often have a lot of the performance and evidence information that historically has been left off the budget requests.

- Governor’s Office – Ultimately, they decide what is requested from the legislature.

- Office of Management and Budget – Works for the Governor’s office and administers the budget request process.

Users, Stakeholders & Beneficiaries

- Agency Fiscal Staff – Welcomed the flow of the template even though it was longer.

- Agency Program Staff – Benefit from being empowered to make programmatic arguments to advocate for budget changes.

- Governor’s Office – Are now more confident their recommendations to the legislature will stand up to public scrutiny.

- Office of Management and Budget – Are able to make better budget recommendations to the Governor.

- Legislature – Received the executive branch’s recommended budget with more detail regarding evidence impact.

Innovation Reflections

Results, Outcomes & Impacts

Agencies that took advantage of trainings and office hours, in particular, showed marked improvements. They were more likely, for example, to include citations in their evidence narratives and to provide details on projected cost-benefit ratios. The evidence scale has also motivated agencies to make budget requests for programs with a strong evidence basis rather than other programs. On the Files section, one can see the Pew Results First documentation of this rise in Colorado, now a GFRN state, using a similar methodology. Most importantly the Governor felt she could make better budget decisions and staff felt like they could make better recommendations to her.

Challenges and Failures

To assess the accuracy of the evidence ratings, The Lab performed an independent assessment. Two PhD level scientists, with methodological training, read each of the submissions and provided their own ranking on the Evidence Scale. They did this without knowing what ranking the agency had provided. If the score of those two scientists deviated by more than one point, then another PhD-level methodologist provided a 3rd ranking. Agencies had a tendency to skew their assessment of the level of evidence of their proposals toward the optimistic side. This result shows the need for training and independent evaluation by OMB using the same criteria. Not all agencies fully engaged at the beginning (e.g. about 1 in 3 left the Evidence Scale blank). We put more emphasis on training and technical assistance as a result. The blank Evidence Scales sometimes reflected lingering uncertainty about how to use it (as opposed to opposition to using it).

Conditions for Success

- Executive leadership – the innovation is primarily a transformation of culture and needs the support of senior officials to be successful.

- Evidence Clearinghouses – staff must become familiar with these and have the certainty they must continue to be supported.

- Evidence Scale – While all of them are similar, this must be designed with the government staff to arrive at a scale and process that matches the unique characteristics of the organization.

- Count with expertise in user centered design and evidence developed internally or through temporary external resources.

- Training – This effort involves a lot of education of finance and program staff. Besides Rhode Island, The Lab has done this training with North Carolina and Colorado.

Replication

Five other states, Colorado, Minnesota, North Carolina, Mississippi and Tennessee, all former Pew Results First states and current GFRN states, have developed similar evidence scorecards for their budget development processes. The budget process in each state is somewhat unique in each state with Mississippi being entirely legislative driven. This diversity in application suggests this model can be adapted to municipal as well as state level governments in other countries, potentially national governments as well. A requirement is that the level of budget proposals must match the level of the programs in the evidence clearinghouse database so an accurate evidence rating can be established. It is also important to note that there is no need to spend a lot of money to execute a replication of this project.

Lessons Learned

- Agencies can be overly optimistic about what constitutes evidence. Training is necessary.

- The agency program managers have more ability to demonstrate their programs’ connection to evidence than the agency finance staff.

- When policy officials see evidence ratings that do not match their intuition detailed follow-up is often requested. The quality of the review goes up but the total review process may take longer.

- At the beginning there was confusion about what constitutes 'data'. The term can seem abstract and technical rather than the transactional detail that program managers are often familiar with.

- Agencies that took advantage of trainings and office hours were more likely to include citations in their evidence narratives and to provide details on projected cost-benefit ratios.

- Staff welcomed the new template because it was easier to use. This increased buy-in, which is notable because the form actually demanded more information to complete.

Anything Else?

The Files section has links to the major evidence clearinghouse, our training video, and interactive decision package template. Documents include the evidence scale, rating tool, budget instructions, and the Pew study of Colorado.

Supporting Videos

Status:

- Diffusing Lessons - using what was learnt to inform other projects and understanding how the innovation can be applied in other ways

Date Published:

29 July 2023