Designing for a mission-oriented government in Estonia

A reflection on a workshop co-designed with Piret Tõnurist and Kevin Richman as part of a programme led by Piret Tõnurist.

Building on OPSI’s ongoing systems work, including in Scotland, Finland, and Slovenia, the team travelled to Estonia to learn about their policymaking approach and design a custom workshop module to build capacity around systems-thinking. I am sharing the tools and materials here in case others find them useful.

This session comprised a module in a broader training program for Deputy Secretary Generals (DSGs) of Estonia focused on “policymaking in the age of wicked problems,” a project supported by European Commission. Our systems programme, led by my colleague Piret Tõnurist, suited Estonia’s leadership programme well, particularly the “mission-oriented innovation” work OPSI is developing alongside University College London’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, headed by Mariana Mazzucato.

Beyond intrinsic value of a mission-oriented approach, it also makes Estonia more competitive for European Commission support, especially considering its adoption of a mission-oriented approach for its upcoming Horizon Europe programme. Meanwhile, Estonia has a proliferation of policy strategies, creating many options and few clear paths, something Estonia’s Government Office is working on addressing. Further, while we were reminded, literally during every initial interview, that “Estonia is a small country” there is still sometimes a lack of collaboration across policy areas, especially on topics that are necessarily cross-cutting, like public health and employment issues. Estonia was ripe for a systems-thinking approach based around missions.

The way we work

OPSI does not believe that one-size-fits-all works for public sector innovation, so we first seek to learn before designing projects with governments. In this case, we conducted semi-structured interviews in January with Deputy Secretary Generals and government leadership. In order to encourage an atmosphere of honesty, we apply Chatham House Rule during our interviews and never attribute direct quotes by name. Based on these interviews, we gathered 801 qualitative data points, from which we discovered 50 trends and 7 major systems tensions in the Estonian context.

Then, we designed the workshop to not only test and validate (or reject) these systems tensions with the DSGs but also to enhance DGSs’ skills and capacities for systems-thinking and mission-oriented policy work.

Designing around needs

Through my work developing the Toolkit Navigator and analysing the numerous innovation toolkits in existence, I realised that different tools and methods support different “jobs-to-be-done.” These can be literal problem solving tasks or more cognitive or group behavioural jobs. While many toolkits emphasise the problem-solving tasks (naturally, since these are the most visible and tangible), wicked, complex problems also require much more sense-making and re-thinking, especially as the number of humans involved increases. These are very different kinds of jobs and these are especially important when designing interactions in a workshop. For instance, something I learned about Estonian culture is that it takes people a while to warm up to a conversation, so this needed to be accounted for in the workshop design.

Design goals and jobs-to-be-done at the workshop:

- Interaction among DSGs that are atypical collaborators (such as between the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Agriculture)

- Take advantage of the intrinsic competitiveness in the group

- Create a sense of playfulness that allows the status quo and existing rituals and constraints to be temporarily abandoned

- Build group around DSGs’ role in policymaking

- Building confidence in DSGs’ leadership of systems change

- Increase exposure and relevance of a mission-orientation in policymaking

- Explore and test the 7 systems tensions we uncovered during discovery interviews

- Address the “proliferation of strategies” issue identified by the Estonian Government

- Exposure to a broad spectrum of methods for different types of innovation

- Build exposure and experience with specific tools connecting policy strategy with policy implementation

- Build exposure and experience with systems-thinking tools and methods

- Build skills in and experience with pitching and storytelling

- Uncover fragilities in existing policymaking system and dissect them in a safe space

Workshop summary and free tools

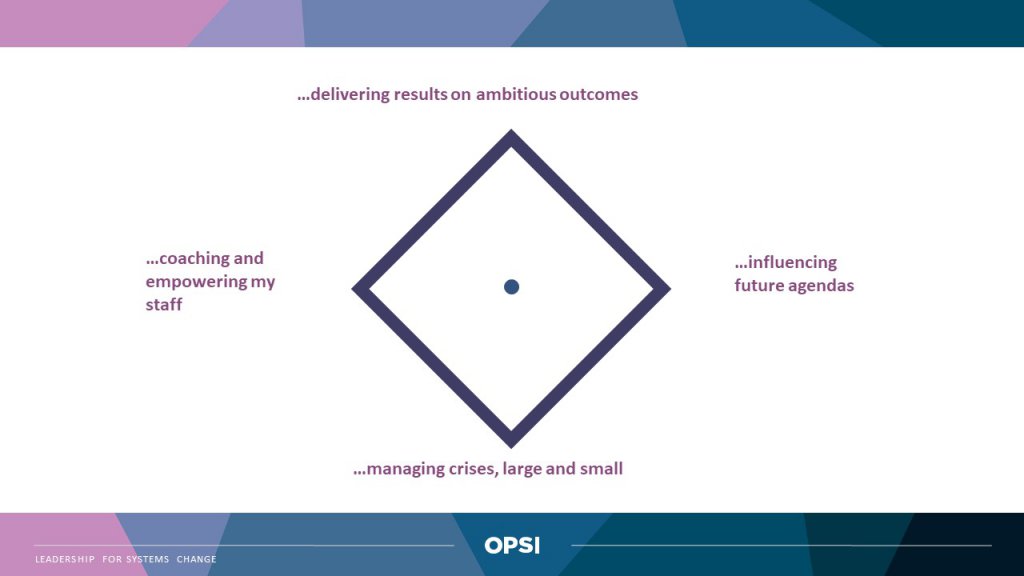

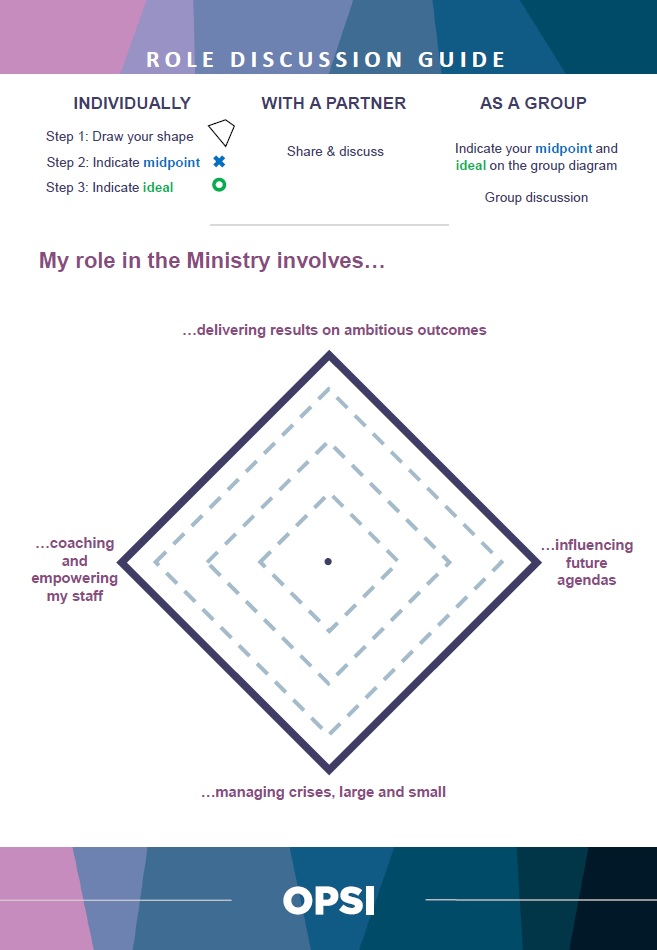

After an introduction to systems-thinking and an overview of our methodology, we took participants through an exercise around their role as a Deputy Secretary General in their respective ministries. We asked, individually, in pairs, then as a group, “My role in the Ministry involves…”

These roles were loosely based on the OPSI Innovation Facets Model.

We asked DSGs to define the balance of time spent in each role, the midpoint of the resulting shape, as well as the midpoint of their ideal state.

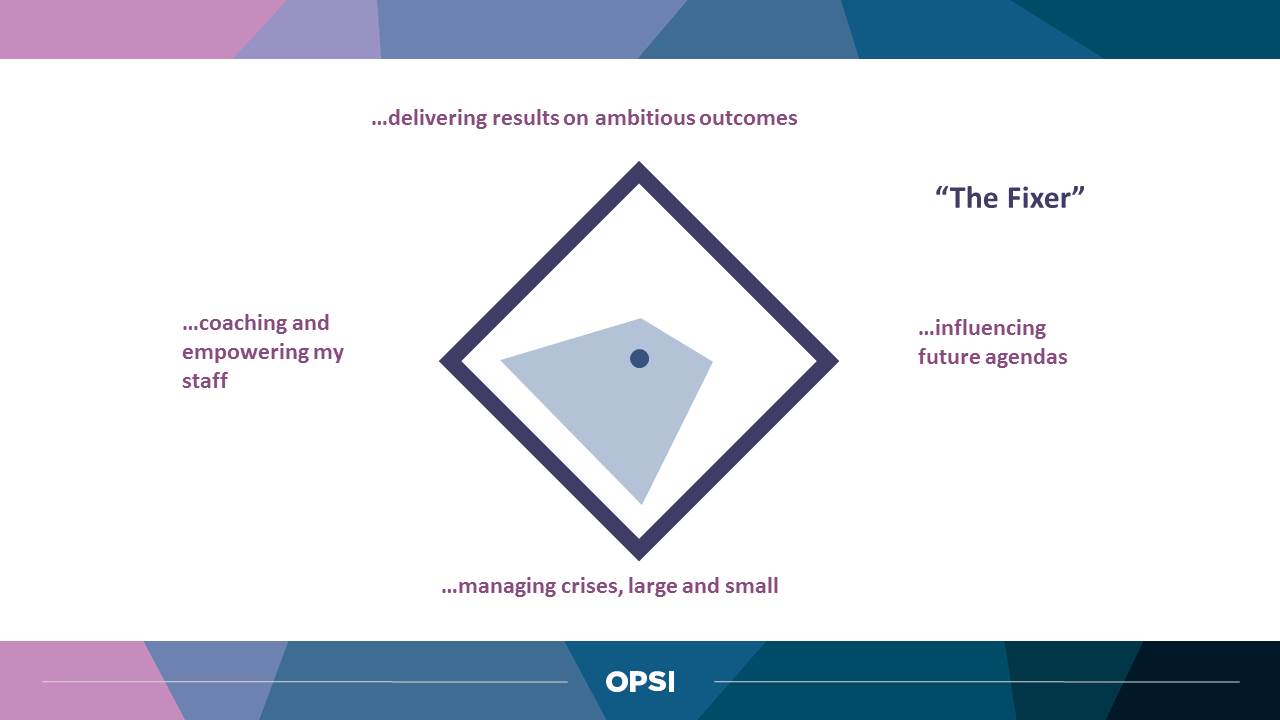

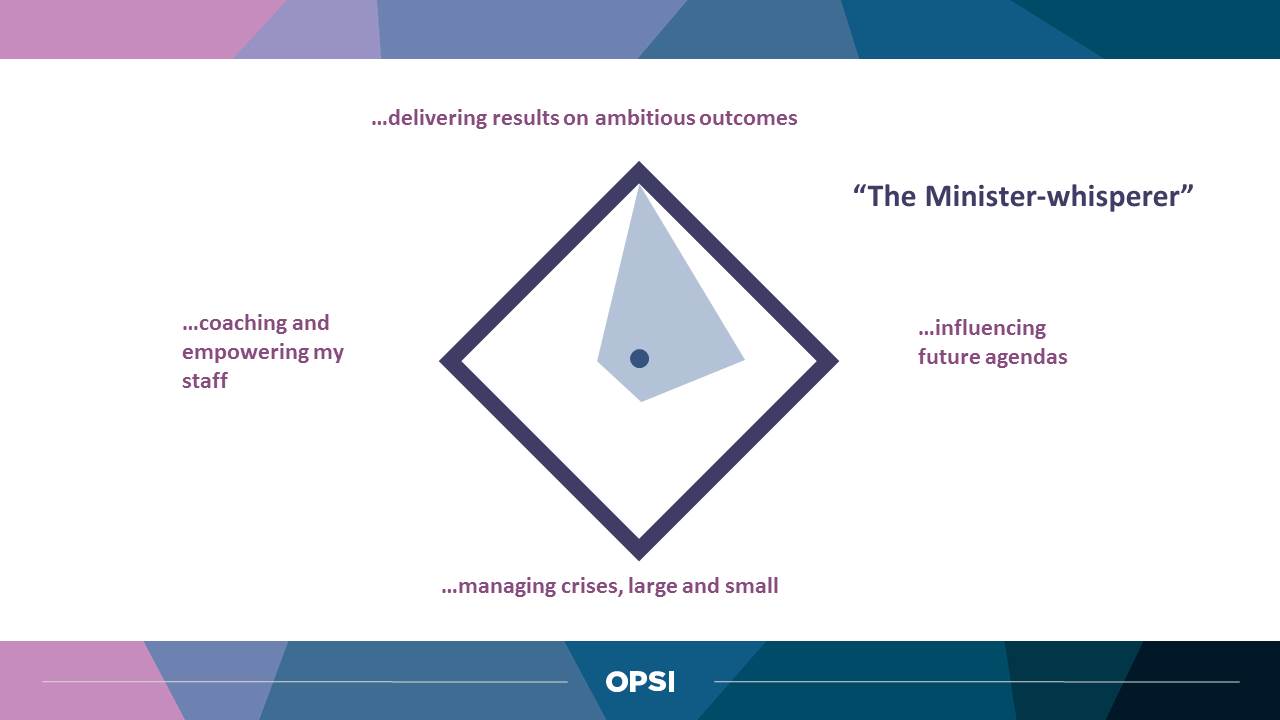

For instance, a few hypothetical personas:

After a discussion with their peer partners, we asked participants to share their midpoints (current and ideal) with the whole group. This helped uncover, as a whole, how DSGs see their role, currently and in the future.

If you would like to run the activity, you may use this tool:

After a primer on systems-thinking and an overview of mission-oriented innovation cases from around the world, we took the participants through a group exercise to dissect a mission-oriented project and then apply the topic to their own context. The goals of this exercise were to build their practice in connecting policy development with policy implementation as well as pitching and storytelling, both mission-oriented innovation needs identified in the discovery process. The activity was designed to identify the mission itself—which is an entirely different strategy exercise. We assume the case of a pre-defined mission by their ministers and it is the DSGs job to communicate and deliver on it.

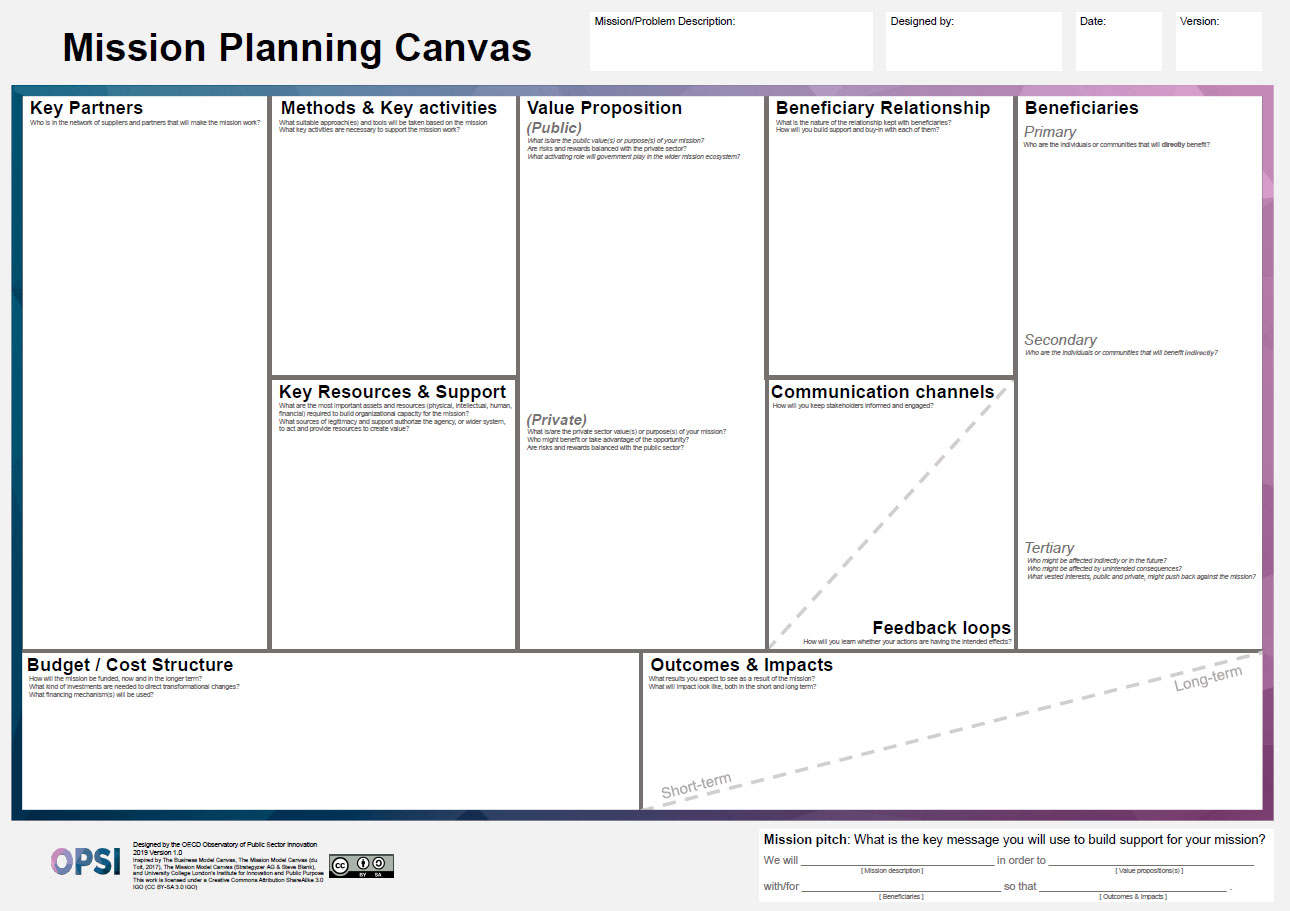

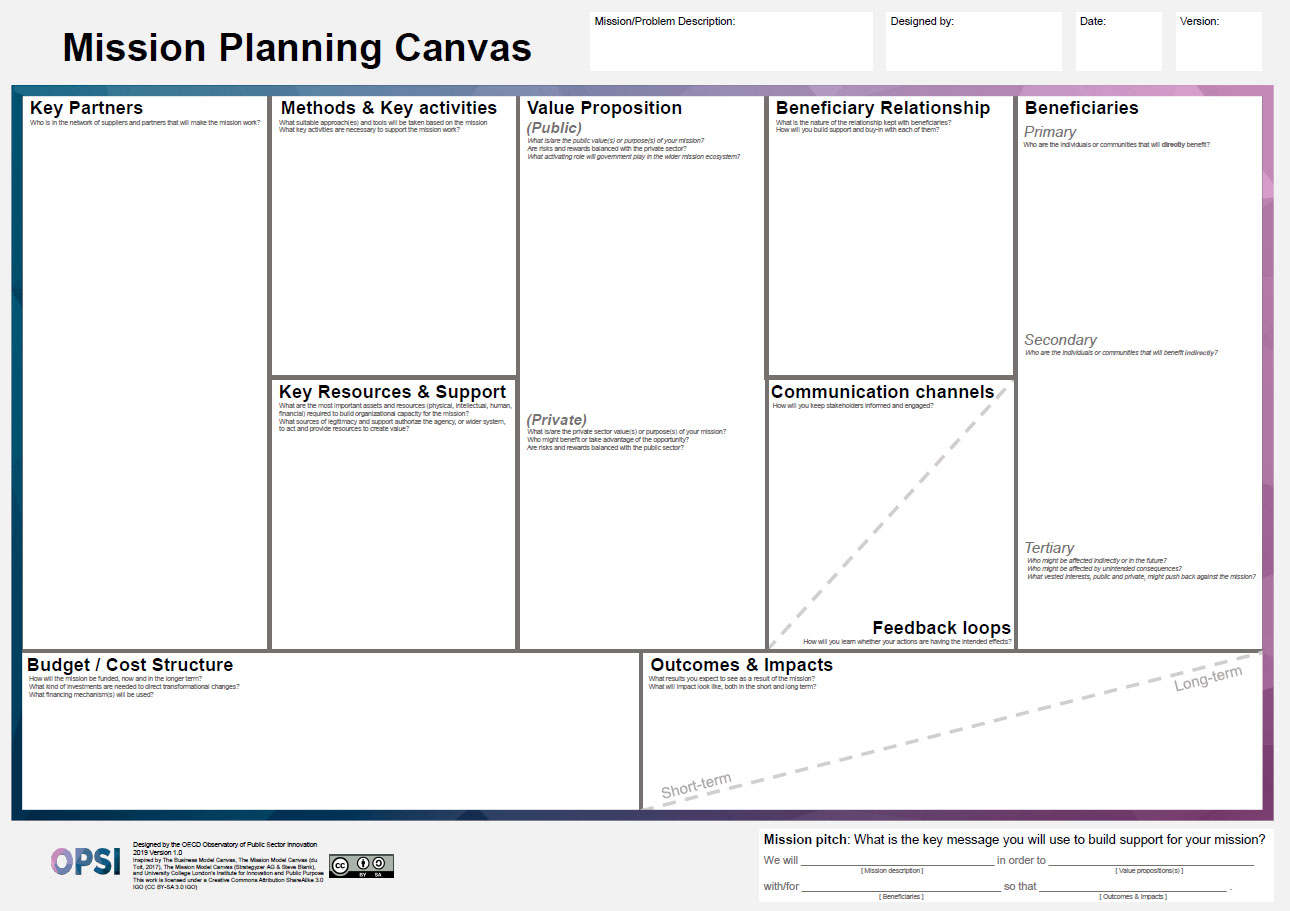

For this activity, we adapted the Business Model Canvas, a widely used business model design tool used to connect customer value to business activities. Based on the analysis of Mission Model Canvas and the writings of Mariana Mazzucato on missions (particularly about public versus private value), as well as my own experience attempting to adapt the Business Model Canvas to a regulatory context, the Mission Planning Canvas was born.

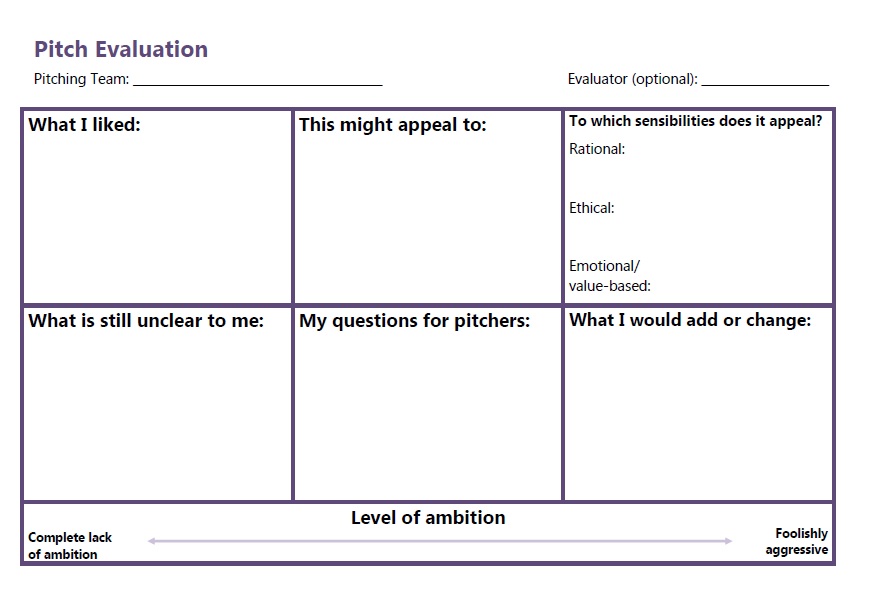

For this workshop, we also added a “pitch template” to the bottom of the canvas to aid groups in communicating their mission based on the elements of the canvas they developed together. To add an element of competitiveness, we framed the pitch as a contest between the groups with each pitch evaluated by their peer DSGs. We identified a need for a future Pitch Design Canvas to frame a good pitch and will incorporate elements from the CURIOUS framework shared by the always-inspirational Dr. Andrea Siodmok from UK Policy Lab. This is a common need for public sector innovation work and if you know of good tools, please share them with the community.

If you would like to run the activity, you may use the Mission Planning Canvas and the pitch evaluation sheet:

Next, we ran the groups through a few mission-oriented innovation activities specific to the Estonian context, including stress-testing their missions, unpacking various embedded challenges in mission delivery, and also connecting appropriate tools and methods. These activities and tools were tailored specifically to the Estonian context, but if you would like to access the tools, please reach out.

In order to make long-term visions operational and deliver on mission-oriented innovation policy, different tools and methods are needed. We shared OPSI’s public sector innovation portfolio approach and shared some specific systems-thinking tools best suited for mission-oriented innovation. Many of these systems tools can be found in OPSI’s Toolkit Navigator.

The last activity built participants’ practice in planning for ways to integrate new methods and tools as well as an experimentation approach into everyday work. The activity was about busting barriers, both real and imagined, standing in the way of delivering on missions. We also designed the activity to get to action—we required that teams develop actionable next steps, including responsible parties and timelines. It is far too easy to come away from a systems-thinking workshop without any tangible and actionable next steps or way of building accountability for taking the steps.

When I reflect on the workshop in Estonia, overall I am shocked by how much we were able to cover in a few days and just how well DSGs were able to absorb new content and switch between international contexts as well as their own. So, it was a great group to test and iterate on our custom-made systems-thinking and mission-oriented innovation tools. If you would like to discuss them with us, if you have suggestions of what you would change about them, or test them and have time to share feedback with us, please reach out.