Effective foresight by governments: an international view

This is a guest post from Anne Pordes Bowers and Peter Glenday of SOIF, the School of International Futures.

COVID-19 has underlined the importance of thinking systemically about the future, even though our institutions are not well structured or incentivised to do this. More urgently than ever, governments need to reinvent how they do strategy and policymaking.

Strategic foresight is an organised, systematic way of looking beyond expected trends to better assess uncertainty and complexity. It is one of several approaches that can help decision-makers to develop more resilient approaches to policy-making. The use of foresight is a central part of anticipatory innovation approaches that help organisations and systems identify signals and take a portfolio approach to solving the problems of tomorrow before they emerge.

While the value of foresight is increasingly understood, the foresight governance field has been evolving slowly. There’s a lot of talk, ideas and good intention – but there is limited evidence on what builds and sustains the impact of foresight work over time at a systems level. The majority of case studies focus on how specific projects or units have used foresight, rather than how governments as a whole have done this.

Our report for the UK Government Office for Science seeks to fix this by exploring how eight countries — Canada, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, The Netherlands, United Arab Emirates and the United States — have developed their foresight systems over time. It presents a framework for thinking about systemic foresight governance, by identifying a common set of features that have supported integration of long-term thinking into strategy and policymaking.

Foresight ecosystems

The UK Government Office for Science is designed to ensure that policies and decisions are informed by the best scientific evidence and strategic long-term thinking. The Futures team, which commissioned the report, plays a central role in building foresight capacity across government, and ensuring policy making is both future-proofed and has a positive impact.

The Futures Team wanted to understand how a range of other countries integrated futures thinking into government. This was to benchmark local practice, to identify ways to improve, and to create a resource for the wider government foresight community on how best to build a resilient foresight ecosystem.

The School of International Futures developed eight international case studies, held a workshop with leading foresight practitioners from different governments across the world, and drew on our own experience of working with more than 50 organisations across the world on their foresight capability and capacity.

There are three lessons from this:

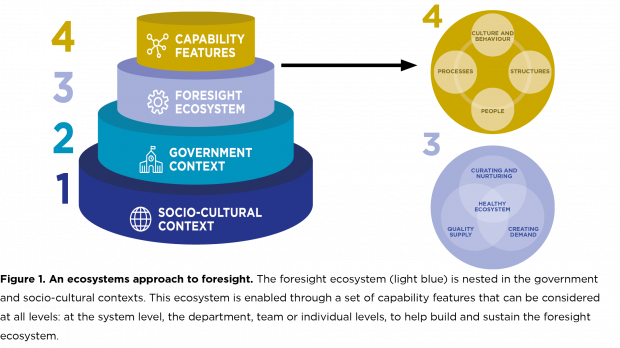

- Strategic foresight capacity needs to be seen as an ecosystem that cuts across all aspects of government. It is built from interwoven, mutually reinforcing roles, responsibilities and activities.

- The socio-cultural and government context matters. This influences a society’s appetite for long-term thinking, comfort with complexity, and uncertainty.

- Future-oriented, resilient and adaptable foresight ecosystems are built out of a common set of features. Different countries have combined these in different ways to build healthy foresight ecosystems.

In the rest of this piece we expand on each of these in turn.

1: Strategic foresight capacity needs to be seen as an “ecosystem”

It is hard to explore policy-making under conditions of deep uncertainty. There are familiar barriers to the use of foresight in policy-making:

- political pressures can be stronger than the incentives to consider the long-term;

- policymakers are more comfortable making decisions based on historic or trend-based data than assessing change;

- policymakers often work in silos; and

- the absence of a central or cross-cutting agenda makes it hard to integrate foresight into policy-making.

The solution is culturally specific. It requires leadership, activity and engagement from across the whole system. Individual foresight units and teams, whether centralised or dispersed, are not of themselves able to achieve the systemic integration that helps countries to be better prepared.

Foresight approaches need to work across the breadth of a country’s governance system. In some countries this includes the civil service; in some, like Finland and Wales, it is the legislature; in the Netherlands it is the judiciary in Netherlands; in New Zealand and the United States it is the Treasury and audit functions. There is also an important role for public participation and engagement.

There are some shining examples of foresight ecosystems in action across the globe. The Finnish legislature has a Committee for the Future which considers future trends and responds to the Government’s Future Report produced by the civil service each term.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) in the US established the Center for Strategic Foresight in 2018 to support “identifying, monitoring, and analyzing emerging issues facing policy-makers”. The GAO both audits US decision-making and makes recommendations to Congress to support them.

In Finland, Sitra is a futures organisation and fund that is responsible for promoting the wellbeing of Finland. It reports directly to Parliament. Sitra’s structure ensures its financial and political independence. The impact of Sitra’s work is measured for Parliament but also “for the people of Finland,” for whom the work was created, developed and distributed.

2: Socio-cultural and government context matters

Foresight ecosystems are specific to their context. How they emerge, are nurtured, and are sustained depends on their local circumstances. Their effectiveness depends on a society’s appetite for long-term thinking, comfort with complexity and uncertainty, and the overall futures literacy—but in turn they can also influence this.

At Level 1 in the diagram above (the socio-cultural context) futures thinking is shaped by the history, geography and indigenous cultures of local or national environments. An example is the commitment by Malaysia to the long-term development of a harmonious, prosperous and sustainable nation. This was enshrined in the Rukun Negara (national principles) proclaimed in 1970 to promote racial harmony and stability. This has influenced Malaysia’s national visioning processes. In New Zealand, Māori culture has a concept of stewardship—kaitiakitanga, which means collective guardianship, for the sky, the sea and the land—that is being embraced in policy-making.

In summary, then, effective government foresight ecosystems need to be designed and evolved in their context.

3: There is a common set of features that have helped countries to build future-oriented, resilient and adaptable foresight ecosystems

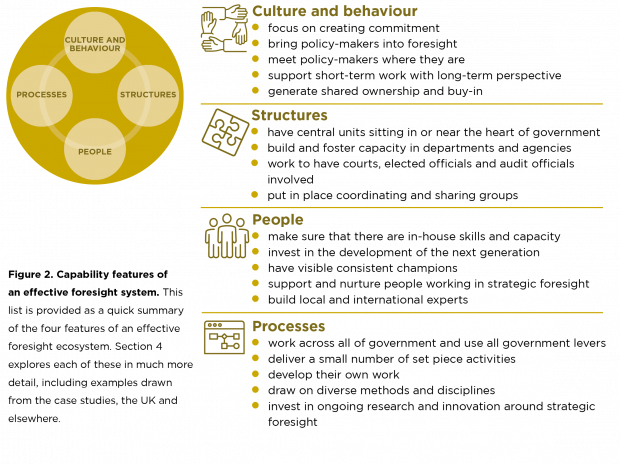

The work found four primary features of effective foresight eco-systems. These can be seen as mutually reinforcing ingredients that together generate ongoing, long-term thinking. They include culture and behaviours, systems, processes and people

While there is no single recipe for creating effective sustainable foresight in government healthy foresight ecosystems commonly have:

- Strong central units that provide a coordinating role and clear mandate for futures work, often linked to national strategy.

- A focus on creating commitment and meeting policy-makers where they are. For instance, in Singapore, the Centre for Strategic Futures works with policy-makers who are focused on short, medium and long-term time horizons. In the United Arab Emirates the foresight leadership team cultivates the right relationships and invests significant effort into ensuring that these relationships remain strong and resilient.

- Consistent, visible champions for futures work that have been a driving force in the development of capability and provided political support for futures work. However, this can lead to vulnerability if there is too much reliance on people at the expense of structures and processes.

- A small number of set piece activities that provide a common language and perspective on the future. These can be wide-ranging trends studies, such as the US National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends report that is published every four years to inform the incoming Presidency, or they can be focused on specific strategic issues, such as the Finland’s Government Report on the Future’ that sets out an agenda for each term of government

- Established networks that focus on knowledge exchange and community-building. The mechanisms vary from hosting ‘foresight Fridays’, national seminars and thematic events in Finland, to building federal and international networks such as the United States Federal Foresight Community of Interest and Public Sector Foresight Network.

- Engaged internationally to identify emerging practice and signals. In Singapore, this is one of the drivers behind the biennial Foresight Week and International Risk Assessment and Horizon Scanning Symposium (IRAHSS). Leaders in the United Arab Emirates have used foresight and futures work to create collaborations between industry, government and the public in a drive to broaden its economic resilience and strengthen its global presence.

- Brought in citizen voices that are often marginalised or absent from policy-making. Long-term vision setting has been used by countries including Malaysia to bring create a national narrative. New Zealand is working to integrate indigenous cultures into the mainstream, while in Singapore the Our Singapore Conversation (2012) facilitated dialogue with citizens around their fears, hopes and aspirations. It included 47,000 participants in 660 sessions at 75 locations and in seven languages to include as many Singaporeans as possible from all areas of life.

- A focus on skills, training and futures literacy. In Singapore, foresight skills are a core part of civil service training for new and senior positions. In Malaysia, the focus has been on building capacity among young people and supporting futures literacy.

Putting it all together

Successful foresight ecosystems are built through a series of actions that cover all four of the features (Culture and behaviour, Processes, Structures and People) over time. The priority and phasing for any given foresight ecosystem will be shaped by a system’s development and national context.

The options available to you – whether as a political leader or policy-maker – will depend on where you are in the system, your local context and the resources and capabilities at your disposal.

- If you are able to think widely and look across the governance system, then look at the different roles that parliament, audit, treasury and other actors can play.

- Connect supply and demand. Take time to build relationships with decision-makers, and help them to engage with existing insight and thinking.

- Nurture your system, and bring your champions and advocates together with others to break down silos. Develop foresight skills and capability and futures literacy at all levels.

- Bring in with diverse voices – including citizen voices and innovative thinkers.

- Be pragmatic. Changing the decision-making process to shift from a short-term mode to a future-facing one takes time. As the stewards of your system, it is about making the most of the opportunities you have and starting on the foresight journey.

- Remember that the ecosystem focus is a means to an end. What matters is that the system is incentivising better decision-making and enabling more effective and resilient approaches to policy-making, including by feeding into anticipatory innovation.

To find out more about building foresight capability in your organisation: SOIF’s Foresight Governance Practice works with the public, private and third sectors around the world. We help already futures-literate organisations to formally embed strategic foresight into their operating models and their ways of thinking, leading and making decisions.

Contact [email protected] for more information.