Global Trends in Government Innovation 2023

The global context

Governments worldwide have faced severe challenges in the last few years. The world had little time to recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation dealt the global economy a series of shocks. The culminative effect of these events has been the destruction of lives and livelihoods, and growing humanitarian, economic and governance crises. Millions of people have been displaced, energy and food markets have been severely disrupted, inflation continues to surge, and economic growth is slowing (OECD, 2022).. Governments must cope with and respond to these emerging threats while already grappling with issues such as climate change, digital disruption The challenges they face in ensuring positive outcomes for their people seem to be increasing.

Yet, despite compounding challenges, governments have demonstrated in many cases capacities for resilience, including for adaptation and innovation. More specifically to the focus of this work, governments have managed demonstrate they are open to changes on how they design policies, deliver services and manage the business of government. If anything, recent and ongoing crises have catalysed public sector innovation and reinstated the critical role of the state. While the overall tone may be pessimistic, public sector innovation has provided bright spots and room for hope.

Governments have been obliged and compelled to continuously innovate. A government cannot continue to deliver unless is innovates, unless it finds a solution for a problem that did not exist a year ago. Innovation is a stabilisation factor, a resilience factor for government.

Mario Nava, Director-General of Structural Reform Support, European Commission at an OECD discussion on “Taking the pulse in OECD democracies“.

The search for these bright spots and entry points for change is the driving force behind this report, and the research that underpins it. As part of the MENA-OECD Governance Programme, the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Mohammed Bin Rashid Centre for Government Innovation (MBRCGI) have collaborated since 2016 to explore how governments are working to understand, test and embed new ways of doing things. These efforts have culminated in 12 reports on Global Trends in government innovation, including this one, as well as a deep-dive effort on achieving Cross-Border Government Innovation to tackle global challenges.

To take the pulse of public sector innovation this year, OPSI and the MBRCGI have identified and analysed 1 084 innovative initiatives from 94 countries around the world (download CSV).

Figure 1: Innovation initiatives analysed for this report

This wealth of innovative activities among governments and their partners in industry and civil society by far surpasses the level of innovation observed in previous years, demonstrating that governments are willing and able to step up and take rapid and impactful action to overcome the obstacles in their path and to help ensure the wellbeing of their citizens and residents.

Through synthesising the identified projects and taking into account events, workshops and conversations held with governments around the world, OPSI and the MBRCGI have identified four key trends and 10 case studies that illustrate them.

As can been seen throughout this report, government responses to COVID-19, and their efforts to move towards long-term recovery, permeate several of these trends, and in many cases serve as the point of origin for their underlying initiatives. In many ways, the four leading trends represent the systemic evolution and maturity of government priorities and workstreams already underway, rather than the introduction of radically new concepts. Accountability, public care services and protecting cultures and marginalised groups are age-old functions of government. Likewise, governments have been working to open their systems to the public for several decades now. Yet, recent events, new technologies, growing expectations from citizens and increasing awareness of inequities and injustices in society have compelled and empowered governments to act in new ways. While the resulting efforts in recent years were often ad-hoc, those seen this year, while still innovative in their approach, are often more intentional, building on lessons learned from previous efforts and seeking to address the root cause of issues rather than symptoms.

In addition to the four leading trends, a number of additional secondary trends emerged. Although these are not the focus of this report, OPSI and the MBRCGI plan to touch on them in future work. These secondary trends include:

- Public administration transformation. Governments are innovating to transform nuts-and-bolts operations, such as procurement, training and reskilling and upskilling public servants, and seeking to measure public sector innovation.

- New foundations for young people and intergenerational justice. Governments are developing novel solutions tailored to the needs of young people and giving a voice to future generations in today’s policy making.

- Accelerating the path to net zero. Governments are taking creative approaches to reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainable approaches.

- Strengthening and leveraging GovTech ecosystems. Governments are reaching beyond the public sector for innovative solutions and tapping into new ideas from agile startups.

OPSI and the MBRCGI celebrate these efforts and hope that they inspire others to take action and replicate their success in their own context. The partners behind this project also greatly appreciate the work of the individuals, teams and organisations who are undertaking innovation projects and took the time to participate in the Call for Innovations that fuelled this work. For instance, innovators in Brazil submitted an astounding 112 cases, with 53 coming from Greece, and 35 or more from Colombia, Korea and Türkiye. Although not all the efforts uncovered for this work can be featured in this report, many are available on the OPSI Case Study Library, a constantly growing resource where public servants can learn about innovative projects around the world, and even reach out to the teams behind them to learn more.

Figure 2: OPSI Case Study Library

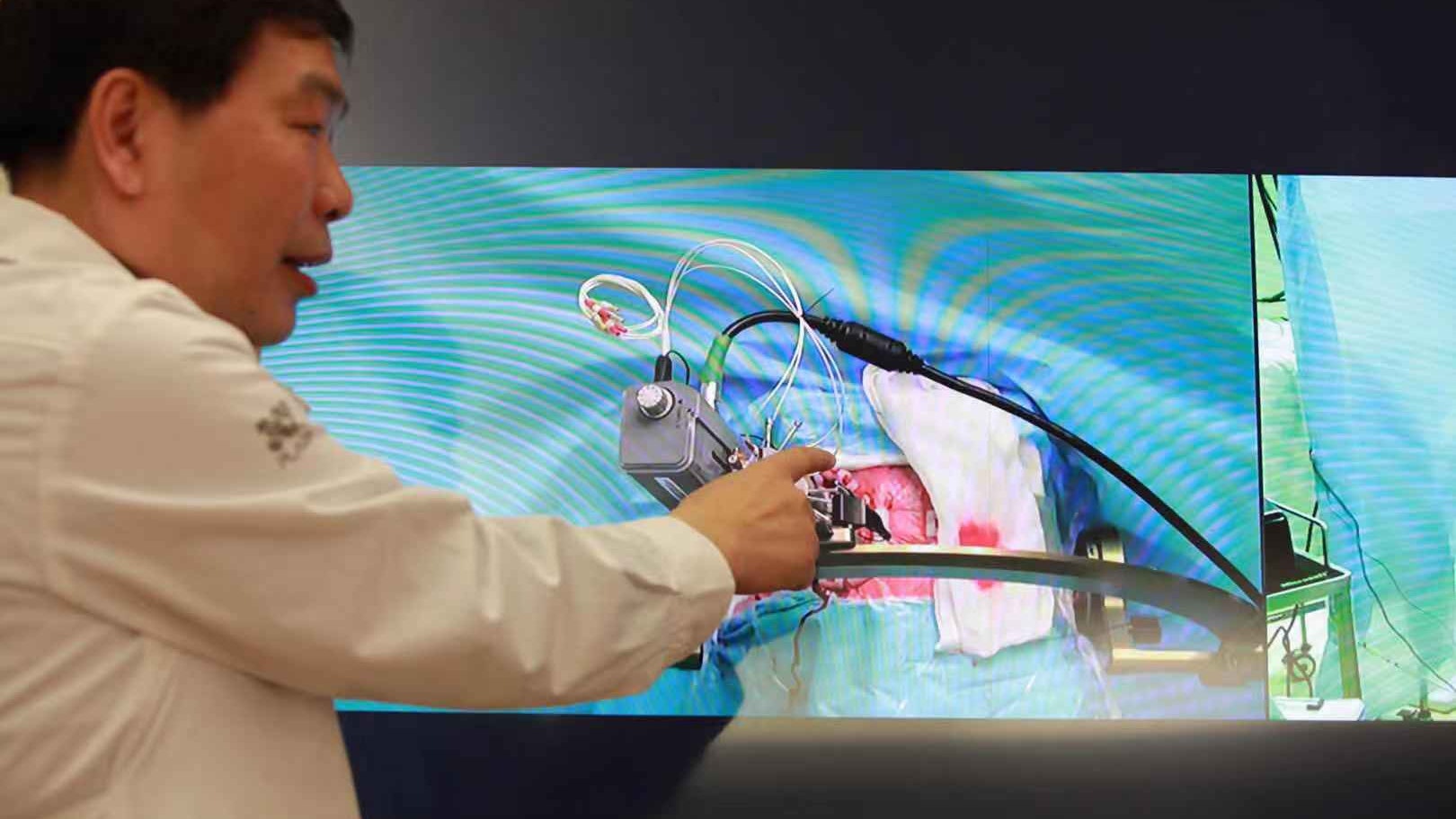

As with previous editions, this Global Trends report is published in conjunction with the World Government Summit (WGS), which brings together over 4 000 participants from more than 190 countries to discuss innovative ways to solve the challenges facing humanity. A flagship feature of the event is Edge of Government, a series of interactive exhibits that bring innovations to life and puts innovation teams on the world stage. These exhibits include several of the case studies presented in this review.

Figure 3: The Edge of Government experience

Trend 1: New forms of accountability for a new era of government

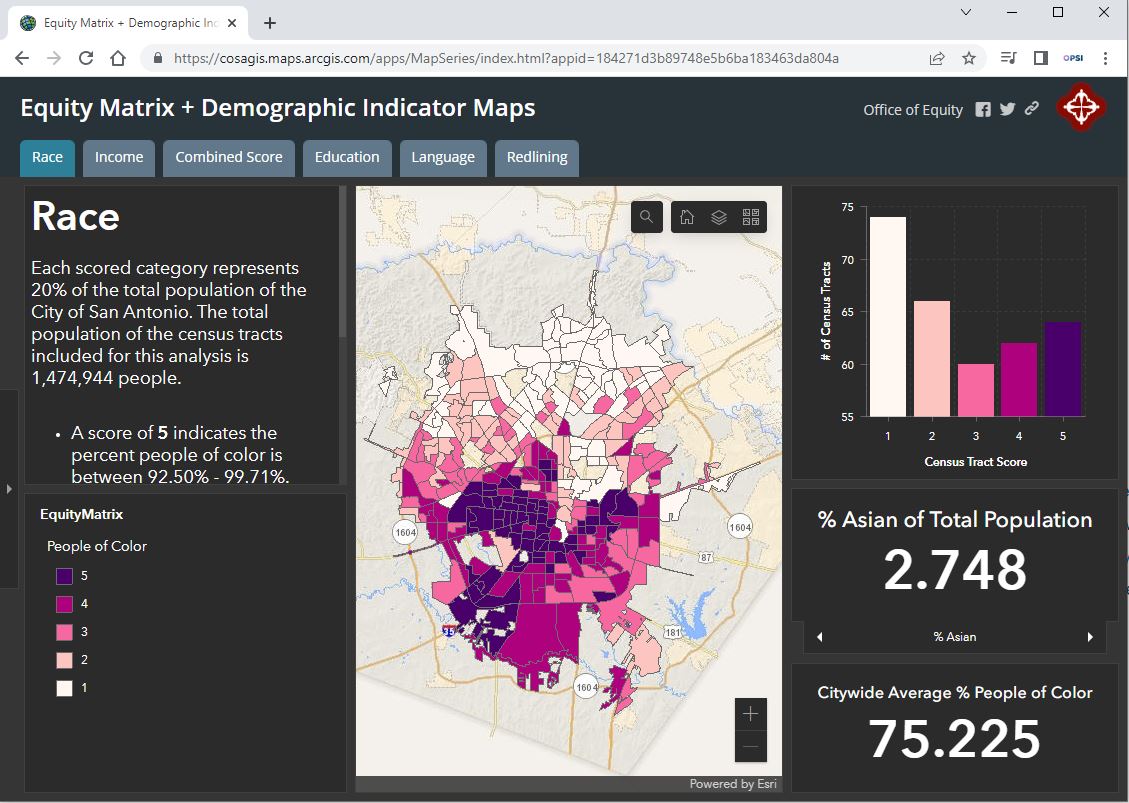

Governments are increasingly incorporating Artificial Intelligence into the design and delivery of public policies and services. This move is accompanied by efforts to ensure that the underlying algorithms and data avoid bias and discrimination and that public servants understand data ethics. Several forward-thinking governments and external ecosystems actors are promoting algorithmic accountability, emphasising transparency and explainability with a view to building trust with citizens. Beyond algorithms, governments are promoting new concepts of transparency with the evolution of Rules as Code – open and transparent machine-consumable versions of government rules. They are also evaluating privacy issues related to the Internet of Things, notably the embedding of often-invisible sensors into public spaces. While innovative policy efforts in these areas are promising, they remain often scattered and lack coherence, limiting the potential for collective learning and the scaling of good ideas. This underlines the need for further work on these topics, including by fostering international alignment and comparability.

Algorithmic accountability

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping economies, promising to generate productivity gains, improve efficiency and lower costs. As governments determine national strategic priorities, public investments and regulations, they hold a unique position in relation to AI. Many have acknowledged the economic importance and potential of AI, with AI strategies and policies now in place in more than 60 countries worldwide.

The OECD.AI Policy Observatory has taken the lead in advancing OECD’s AI-related efforts. An important milestone was the adoption of the OECD AI Principles in 2019. This pioneering set of intergovernmental standards on AI stresses the importance of ensuring that AI systems embody human-centred values, such as fairness, transparency, explainability and accountability, among others.

The majority of national AI strategies recognise the value of adopting AI in the public sector, alongside the need to mitigate its risks (OECD/CAF, 2022; OECD 2019). In fact, governments are increasingly using AI for public sector innovation and transformation, redefining how they design and deliver policies and services. While the potential benefits of AI in the public sector are significant, attaining them is not an easy task. The field is complex and has a steep learning curve, and the purpose and context of government presents unique challenges. In addition, as in other sectors, public sector algorithms and the data that underpin them are vulnerable to bias, which may cause harm, and often lack transparency.

The OECD Open and Innovative Government Division (OIG) has undertaken extensive work on the use and implications of AI and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms in the public sector to help governments maximise the positive potential impacts of AI use and to minimise the negative or otherwise unintended consequences (see examples here, here and here). Other organisations, including the European Commission, have also reviewed and examined the expanding landscape of AI in the public sector.

However, the rapid growth in government adoption of AI and algorithmic approaches underlines the need to ensure they are used in a responsible, ethical, trustworthy and human-centric manner. Perhaps more than any other sector, governments have a higher duty of care to ensure that no harm occurs as a result of AI adoption. Such potential consequences include the perpetuation of “Matthew effects”, whereby “privileged individuals gain more advantages, while those who are already disadvantaged suffer further” (Herzog, 2021). For instance:

- The “Toeslagenaffaire” was a child benefits scandal in the Netherlands, where the use of an algorithm resulted in tens of thousands of often-vulnerable families being wrongfully accused of fraud and even hundreds of children being separated from their families, resulting in the collapse of the government.

- Australia’s “robodebt scheme” leveraged a data-matching algorithm to calculate overpayments to welfare recipients, resulting in 470 000 incorrect debt notices totalling EUR 775 million being sent. This led to a national scandal and a Royal Commission after many welfare recipients were required to pay undue debts.

- In the United States, the use of facial recognition algorithms by police has resulted in wrongful arrests, while bias has been uncovered in criminal risk assessment algorithms that help guide sentencing decisions, resulting in harsher sentences for Black defendants.

- Serbia’s 2021 Social Card law allows for the collection of data on social assistance beneficiaries using an algorithm to examine their socio-economic status. As a consequence, over 22 000 people have lost benefits without an explanation, resulting in legal petitions by a network of advocacy groups (Caruso, 2022).

Government have sought to address this issue in a variety of ways, including outright bans on some types of algorithms. For instance, in Washington, DC, the proposed “Stop Discrimination by Algorithms Act“ prohibits the use of certain types of data in algorithmic decision making, and at least 17 cities in the United States and even entire countries, such as Morocco, have implemented bans on government usage of facial recognition. However, a number of have since backtracked, and OECD OPSI-MBRCGI’s prior report on Public Provider versus Big Brother shows that while authoritarian governments have employed algorithms as a means of social control (e.g. China’s Social Credit System), others have applied them in legitimate ways to deliver better outcomes for the public. Some even argue that algorithmic decision making can counteract unaccountable processes and offers “a viable solution to counter the rise of populist rhetoric in the governance arena” (Cavaliere and Romeo, 2022).

While algorithms can indeed introduce bias and discrimination, so can humans. Indeed, algorithms can systematise the human bias observed in human decisions (del Pero, Wyckoff and Vourc’h, 2022). The key to prevention is having the right safeguards and processes in place to ensure ethical and trustworthy development and use of AI technologies and to mitigate potential risks and biases, as emphasised by the 2023 European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade. One example of this approach is algorithmic accountability.

Algorithmic accountability means ‘ensuring that those that build, procure and use algorithms are eventually answerable for their impacts.’

Source: The Ada Lovelace Institute, AI Now Institute and Open Government Partnership

Broadly speaking, accountability in AI means that AI actors must ensure that their AI systems are trustworthy. To achieve this, accountable actors need to govern and manage risks throughout their AI systems (OECD, forthcoming-a, Towards accountability in AI). The concept of algorithmic accountability more specifically is rooted in “transparency and explainability“ and broader “accountability“, values that are integral to the OECD AI Principles. However, current legal and regulatory frameworks around the world lack clarity regarding these values, especially about the use of algorithms in public administrations. For instance, the European Union (EU)’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides rules and remedies related to algorithmic decisions, but the question of whether explainability is also a requirement has given rise to much debate (Busuioc, 2020). The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) (passed in July 2022), Canada’s proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA), and the United States’ proposed Algorithmic Accountability Act (AAA) all include requirements for enhanced transparency for algorithms, but are generally aimed at companies, leaving the question of how public administrations should use algorithms open to interpretation. The proposed EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) and the related EU AI Liability Directive, however, offer significant potential for algorithmic accountability in the public sector (Box 1).

Box 1: Algorithmic accountability in the proposed AI Act and AI Liability Directive

Proposed in 2021, the AI Act is the first piece of regulation that specifically addresses the risks of AI. The Act tackles gaps in current European legal frameworks by adopting a risk-based approach. It sets four levels of risk for AI: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal or no risk.

All forms of AI deemed to present an unacceptable risk will be banned as a threat to people’s rights, safety and livelihoods. Those in the high risk category, such as biometric identification systems, will be subject to stricter obligations, which include appropriate human oversight measures, high-quality training datasets, and risk assessment and mitigation mechanisms. Limited risks AI systems will comply with lighter obligations that focus on transparency and ensure that users are aware that they are interacting with a machine. The use of minimal or no risk AI systems, which constitute the majority of those currently used in the EU, will be free or restriction.

To establish a shared framework to address the legal consequences of harms caused by AI systems, in September 2022 the Commission proposed the AI Liability Directive. With this policy the Commission wants to ensure that victims of harm caused by AI are not less protected than those of traditional technologies. The policy would decrease the burden of proof for victims, establish a “presumption of causality” against the developer, provider or user of the AI system, and make it simpler for victims to obtain information about high-risk systems – as defined by the AI Act – in court.

Source: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_5807.

As the international landscape continues to evolve and solidify, a number of forward-thinking governments worldwide are promoting algorithmic accountability, led largely by oversight and auditing entities, as well policy-making bodies often located at the centre of government. External ecosystems actors are also taking note and are working to ensure the use of algorithmic approaches in government meet the higher duty of care required of the public sector. However, despite these promising approaches, more needs to be done to build alignment among disparate definitions and practices around the world.

From the inside-out: Innovative government efforts in algorithmic accountability

Independent oversight entities have a critical role to play in auditing the use of algorithms in the public sector. Such algorithmic accountability can be seen in a variety of examples from around the world:

- In a first for the Latin American region, the independent Chilean Transparency Council is developing an open and participatory design for a binding “General Instruction on Algorithmic Transparency“ for public entities. A public consultation is expected for 2023.

- The Netherlands Court of Auditors (NCA) has made significant advances in both front-end and back-end aspects of algorithmic accountability. In 2021, it developed an audit framework that assesses whether algorithms meet quality criteria. In 2022, it audited nine major public sector algorithms and found that six (67%) did not meet basic requirements, exposing the government to bias, data leaks and unauthorised access.

- In 2022, Spain created an independent Spanish Artificial Intelligence Supervision Agency (Box 2), and the Netherlands launched a similar entity in 2023. The draft AI Act (Box 1) also calls for a supervisory European Artificial Intelligence Board (EAIB).

- In an example of a successful cross-border collaboration, in 2020 the Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) of Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom (UK) collectively issued Auditing machine learning algorithms: A white paper for public auditors.

- The United State Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2021 issued Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities.

The United State Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2021 issued Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities.

Box 2: Spanish Artificial Intelligence Supervision Agency (AESIA)

AESIA was enacted by law in mid-2022 and is the first dedicated national government agency of the EU to implement a direct mandate on supervising, monitoring and building rules on AI, both for the public sector and beyond. The agency was established in response to a proposed AI Act requirement on implementing national supervisory authorities to ensure the application and implementation of the rule of law concerning AI, and to help achieve Spain’s National AI Strategy. The new agency seeks to build a tailored Spanish vision and jurisprudence that could serve as a model for future European AI agencies.

The development of AESIA is a two-step process. First, the design of auditing and implementing guides is key to mainstreaming its vision, and to gathering evidence directly from users needed to build reliable and human-centred regulatory tools. Second, by creating new sandboxes (and incorporating existing ones) with a focus on AI and algorithmic accountability, the agency will be able to test its own rules with a view to achieving objectivity and ensuring that the balance between protecting human and digital rights, and economic interests, is maintained, and that the legitimate interests of all parties are met.

AESIA is expected to be fully operational by late 2023.

Source: www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2021-21653, Interview with AESIA officials.

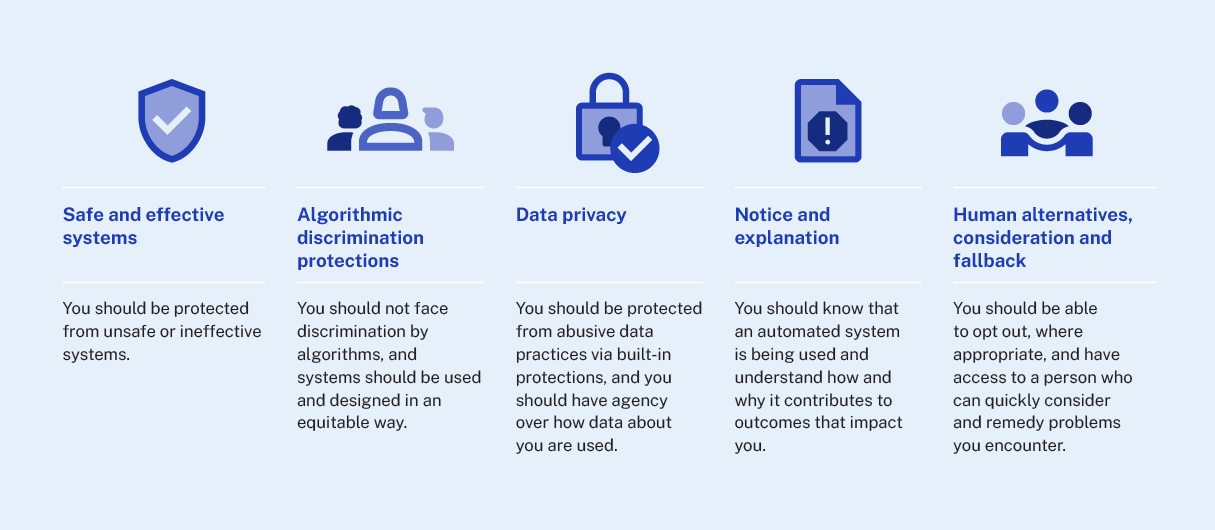

To obtain a complete picture of new forms of accountability, such as algorithmic accountability, it is necessary to look at other players in the public sector innovation and accountability ecosystems. Perhaps the most relevant of these are policy-making offices which set the rules that public sector organisations must follow. One recent example is the October 2022 US White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, which includes five principles and associated practices to protect against harm – although the blueprint has received criticism for excluding law enforcement from its scope. Similarly, Spain’s Charter on Digital Rights includes 28 sets of rights, many of which relate directly to ethical AI and algorithmic accountability, such as “conditions of transparency, auditability, explainability, traceability, human oversight and governance”.

Figure 4: AI Bill of Rights Principles in the United States

Additional relevant examples include:

- In late 2021, the UK Cabinet Office’s Central Digital and Data Office issued one of the world’s first national algorithmic transparency standards, which is being piloted with a handful of agencies (see full case study later in this publication). Relatedly, the United Kingdom, through The Alan Turing Institute (see p. 167 of OPSI’s AI primer for a case study on its Public Policy Programme), has also created an excellent AI Standards Hub to advance trustworthy AI through standards such as the Algorithmic Transparency Standard.

- Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision Making, issued by the Treasury Board Secretariat, requires agencies using or considering any algorithm that may yield automated decisions to complete an Algorithmic Impact Assessment. This questionnaire calculates a risk score which in turn prescribes actions that must be taken (OPSI’s report on AI in the public sector includes a full case study). Canada’s Algorithmic Impact Assessment has inspired similar mechanisms in Mexico and Uruguay.

- France’s Etalab has issued guidance on Accountability for Public Algorithms, which sets out how public organisations should report on their use to promote transparency and accountability. The guidance proposes six principles for the accountability of algorithms in the public sector, among other elements.

- The Netherlands’ Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations has created a Fundamental Rights and Algorithms Impact Assessment (FRAIA), which facilitates an interdisciplinary dialogue to help map the risks to human rights from the use of algorithms and determine measures to address these risks.

- At the local level, policy offices in the cities of Helsinki, Finland and Amsterdam, the Netherlands have developed AI registers to publicly catalogue AI systems and algorithms, while a policy office in Barcelona, Spain, has developed a strategy for ethical use of algorithms in the city. Based on Helsinki and Amsterdam’s work, in 2023 nine cities have collaborated through the Eurocities network to create an algorithmic transparency standard.

In addition to these internal government approaches, countries have adhered to non-binding international recommendations and principles for responsible and ethical AI that could guide this work. Such examples include the aforementioned OECD AI Principles and UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI. The development of such instruments continues, for example through the Council of Europe, which has a committee dedicated to AI (CAI) that is developing a Legal Instrument on Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law. In regard to accountability, the OECD.AI Policy Observatory is working to make principles more concrete through its Working Group on Tools & Accountability and collaboration around the prototype OECD-NIST Catalogue of AI Tools & Metrics.

Alongside these initiatives scoped specifically around AI and algorithms, the application of broader open-by-default approaches can help make governments algorithms more accountable to their people. In this regard, the OECD Good Practice Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector underscore the need to make source code openly available for public scrutiny and audit and the need for more control over data sources informing AI systems (see Box 3). Other examples in this area include the Open Source Software initiative implemented by Canada in the context of its OGP Action Plan, as well as France’s application of open government in the context of public algorithms.

Box 3: OECD Good Practices Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector

- Manage data with integrity.

- Be aware of and observe relevant government-wide arrangements for trustworthy data access, sharing and use.

- Incorporate data ethical considerations into governmental, organisational and public sector decision-making processes.

- Monitor and retain control over data inputs, in particular those used to inform the development and training of AI systems, and adopt a risk-based approach to the automation of decisions.

- Be specific about the purpose of data use, especially in the case of personal data.

- Define boundaries for data access, sharing and use.

- Be clear, inclusive and open.

- Publish open data and source code.

- Broaden individuals’ and collectives’ control over their data.

- Be accountable and proactive in managing risks.

Source: https://oe.cd/dataethics.

From the outside-in: Broader ecosystems strengthening accountability

While innovative and moving in the right direction, government algorithmic accountability efforts are currently scattered and lack coherence, which limits the potential for collective learning and the scaling of good ideas and successful approaches. The first step in bringing the global discussion on public sector algorithmic accountability into alignment is understanding the different approaches and developing a baseline for action. Some excellent work has already been done in this area, with the joint report of the independent Ada Lovelace Institute, AI Now Institute and OGP representing “the first global study of the initial wave of algorithmic accountability policy for the public sector”. Their work surfaced over 40 specific initiatives, identified challenges and successes of policies from the perspectives of those who created them, and synthesised some findings on the subject.

Box 4: Six determinants for the effective deployment of algorithmic accountability

- Clear institutional incentives and binding legal frameworks can support consistent and effective enforcement of accountability mechanisms, supported by reputational pressure from media coverage and civil society activism.

- Algorithmic accountability policies need to clearly define the objects of governance as well as establish shared terminologies across government departments.

- Setting the appropriate scope of policy application supports their adoption. Existing approaches for determining scope such as risk-based tiering will need to evolve to prevent under- and over-inclusive application.

- Policy mechanisms that focus on transparency must be detailed and audience appropriate to underpin accountability.

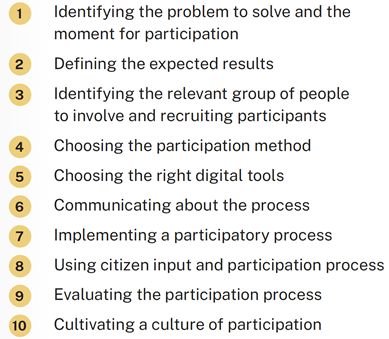

- Public participation supports policies that meet the needs of affected communities. Policies should prioritise public participation as a core policy goal, supported by appropriate resources and formal public engagement strategies.

- Policies benefit from institutional co-ordination across sectors and levels of governance to create consistency in application and leverage diverse expertise.

Source: www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/algorithmic-accountability-public-sector.

Additional relevant work has been conducted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) to develop technical standards or quality specifications approved by a recognised standardisation body. These can be powerful tools to ensure that AI systems are safe and trustworthy, and include, for instance, ISO/IEC TR 24028:2020 on trustworthiness in AI and IEEE’s Ethics Certification Program for Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (ECPAIS). Furthermore, the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), the world’s largest scientific and educational computing society, through its global Technology Policy Council, has issued a set of Principles for Responsible Algorithmic Systems, which focus on relevant issues such as legitimacy and competency, minimising harm, transparency, explainability, contestability and accountability. The principles are accompanied by guidance on how to apply them while considering governance and trade-offs.

External actors in the accountability ecosystem are also working to hold governments accountable, or to assist them in doing do. Accountability ecosystems encompass “the actors, processes and contextual factors, and the relationships between these elements, that constitute and influence government responsiveness and accountability, both positively and negatively” (Halloran, 2017). This shift towards transparency and accountability combined with ever-growing Civic Tech, Public Interest Tech and GovTech movements, have expanded accountability ecosystems to incorporate a complex fabric of civil society organisations, academic institutions, private companies and individual members of the public. When leveraged well through partnerships, external ecosystems actors can even help governments compensate for a lack of institutional capacity in this space, as seen in the OECD’s (2021i) work with cities.

As governments continue to push for more transparency in source code and algorithms, the interactions within these broader accountability ecosystem actors are poised to grow. A cluster of interesting examples of this dynamic can be seen in the Netherlands, which is shaping up to be a leader in algorithmic accountability both inside and outside government. Algorithm Audit is a Dutch nonprofit organisation that strives for “ethics beyond compliance”. It builds and shares knowledge about ethical algorithms, and includes independent audit commissions that shed light on ethical issues that arise in concrete use cases of algorithmic tools and methods. In another example, the Foundation for Public Code‘s “codebase stewards” help governments publish transparent code in alignment with its Standard for Public Code, which aims to enhance trustworthy codebases.

Additional relevant examples include:

- European Digital Rights (EDRi), the biggest European network defending rights and freedoms online, consisting of 47 non-governmental organisation members and dozens of observers.

- AI Sur, a consortium of organisations that work in civil society and academia in Latin America, which seek to strengthen human rights in the digital environment of the region.

- AlgorithmWatch, a non-profit research and advocacy organisation committed to watching, unpacking and analysing automated decision-making systems and their impact on society.

The emergence of a growing body of GovTech startups (see Box 5 for a definition) is also helping governments and other organisations achieve algorithmic accountability (Kaye, 2022). Forbes has listed the rise of GovTech startups as one of the five biggest tech trends transforming government in 2022, and there are signs of these companies entering the algorithmic accountability space. For instance, Arthur, Fiddler, Truera, Parity and others are actively working with organisations on explainable AI, model monitoring, bias identification and other relevant issues. While most activities so far appear to support private sector companies, the public sector potential is significant, as is evident in the selection of Arthur by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) to monitor AI accuracy, explainability and fairness in line with the DoD’s Ethical AI Principles.

Box 5: Definition of GovTech

GovTech is the ecosystem in which governments co-operate with startups, SMEs and other actors that use data intelligence, digital technologies and innovative methodologies to provide products and services to solve public problems… They propose new forms of public-private partnerships for absorbing digital innovations and data insights to increase effectiveness, efficiency and transparency in the delivery of public services.

The emergence of external accountability ecosystem actors is a positive development. One of the most positive outcomes of algorithmic accountability policies and processes, such as the Open Government Data efforts that preceded them, is to empower non-governmental actors to scrutinise and shed light on public sector activities. As governments continue to empower these players through the provision of open data and algorithms and develop accountability mechanisms for better responsiveness, OPSI and the MBRCGI expect to see continued growth of these types of initiatives in the near term.

Additional action needed going forward

Governments and other ecosystems actors have made tremendous progress in this area in just a few years. A spectrum of approaches is unfolding with efforts exhibiting differing levels of maturity. For instance, most standards and principles around the world represent high-level, non-binding recommendations, but concrete laws like the EU’s AI Act and US Algorithmic Accountability Act are coming into focus and have the potential to catalyse and align progress in this area.

In addition, most algorithmic accountability initiatives now focus on aspects of transparency, with many also incorporating elements of risk-based mitigation approaches. Fewer, though, demonstrate the ability for hands-on auditing of algorithms, which would close the loop on front-end accountability efforts to help ensure trustworthy use of AI in real-world use cases. Recent research from the Stanford Institute for Human-Centred AI (HAI) identifies nine useful considerations for algorithm auditing that can help inform these efforts (Metaxa and Hancock, 2022) (Box 6).

Box 6: Nine considerations for algorithm auditing

- Legal and ethical considerations include relevant laws, the terms of service of different platforms, users involved with or implicated by audits, and personal and institutional ethical views and processes.

- Selecting a research topic can include weighing discrimination and bias issues and political considerations (e.g. political polarisation, a technology’s political impacts).

- Choosing an algorithm to audit includes factoring in international considerations (e.g. which algorithms are popular where) and comparative factors (e.g. auditing one versus multiple algorithms and then comparing them).

- Temporal considerations include how often the algorithm is updated and how the data might change before, during and after an audit is conducted.

- Collecting data requires consideration of the possible available data sources and how analysing the data might scale.

- Measuring personalisation involves considering how personalisation might change algorithms from person to person and how that might impact audits

- Interface attributes require examination of the relationship between interfaces and metadata (e.g. how searches are displayed on a webpage)

- Analysing data involves filtering the data, merging it with external data and choosing points of comparison.

- Communicating findings requires considering the wider public discourse concerning the algorithms.

Source: https://hai.stanford.edu/policy-brief-using-algorithm-audits-understand-ai.

In addition to deepening and iterating their efforts, going forward, governments should work to ensure that public servants involved in building, buying or implementing algorithmic systems are informed about the AI and data ethics principles discussed in this section, and how they can play their part as stewards in ensuring such systems are accountable and serve the public good, alongside other actions in the accountability ecosystem. Such essential efforts range from basic definitional areas up to more sophisticated concepts and approaches. The challenges here have been cited in several studies which found that “in notable cases government employees did not identify regulated algorithmic surveillance technologies as reliant on algorithmic or machine learning systems, highlighting definitional gaps that could hinder future efforts toward algorithmic regulation” (Young, Katell and Krafft, 2019). Furthermore, “definitional ambiguity hampers the possibility of conversation about this urgent topic of public concern” (Krafft et al., 2020). AI Now’s Algorithmic Accountability Policy Toolkit can assist in this effort. It provides “legal and policy advocates with a basic understanding of government use of algorithms including, a breakdown of key concepts and questions that may come up when engaging with this issue, an overview of existing research, and summaries of algorithmic systems currently used in government”.

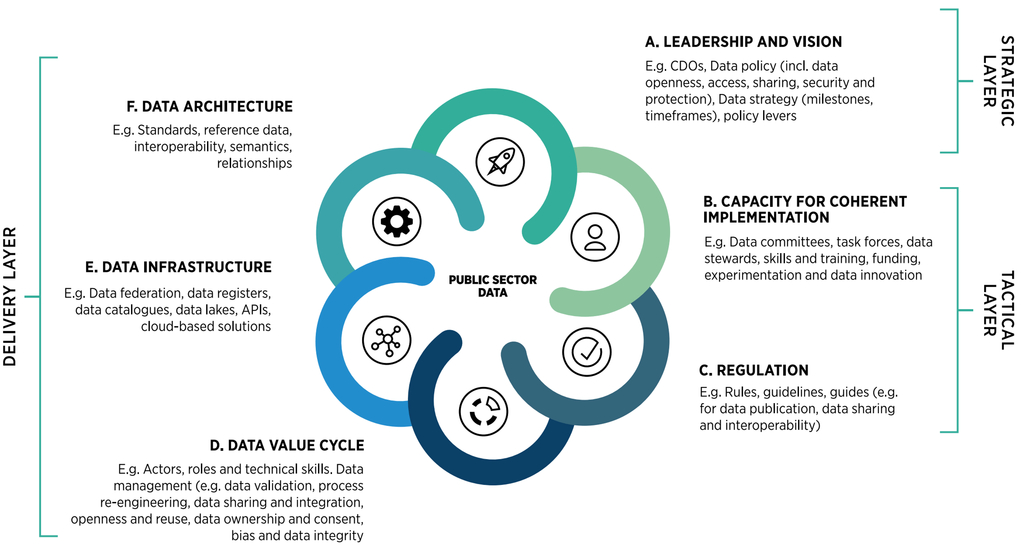

Finally, while this section has focused generally on algorithms and AI systems, governments must also pay close attention to issues related to the underlying data that are used to train modern AI systems. These are touched on in the OECD Good Practices Principles for Data Ethics in the Public Sector (Box 3) and can be seen in the penumbras of examples in this section. To achieve this in a holistic manner, governments must develop and implement robust data governance frameworks and processes across different layers (Figure 5).

Figure 5: OECD Framework for Data Governance in the Public Sector

As can be seen in Figure 5, data governance in the public sector comprises a broad, cross-cutting set of factors that serve as the foundation of a data-driven public sector, the use of data to increase public value and the role of data in building public trust (OECD, 2019a). Data governance intersects directly with and supports algorithmic accountability by helping to ensure the integrity and appropriateness of the underlying data itself along with algorithmic code and risk management processes. Good data governance is inextricably linked with algorithmic accountability but can also be supported by innovative governance techniques. For instance, data audits represent a powerful tool for auditors to assess the quality of data used by AI systems from different perspectives. For instance, auditors can assess if the data source in itself is trustworthy and whether the data are representative of the phenomena to which the AI algorithm is applied. Such data audits have been employed by governments, such as Ireland’s Valuation Office, to ensure accurate evaluations of commercial property. In fact, in 2022 Ireland’s Office of Government Procurement developed an Open Data and Data Management framework that includes data auditing as its primary focus.

The efforts discussed in this trend are building a strong, cohesive foundation to take this innovative area of work to the next level, although much remains to be done. Research is pointing to challenges as governments and private sector organisations move from fragmented and cursory algorithmic accountability efforts to systems approaches that can provide for explainability and auditability, all supported by quality data governance. For instance, without stronger definitions and processes in this space, there is the risk of false assurances through “audit washing” where inadequately designed reviews fail to surface true problems (Goodman and Trehu, 2022).

With the AI Act and other international and domestic rules looming, both governments and businesses will need to make rapid progress at data, code and process levels. Although governments have trailed behind the private sector for many activities related to AI, they also have the potential to be global leaders and practice shapers when it comes to algorithmic accountability. OPSI believes that leading governments are ready to come together to build a common understanding and vocabularies on algorithmic accountability in the public sector, as well as guiding principles for the design and implementation of governmental approaches which could result in tangible policy outcomes. OPSI intends to engage in additional work in this area in the belief that standardisation and alignment of algorithmic accountability initiatives is crucial to enable comparability, while still leaving room for contextual and cultural adaptation.

Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard

Algorithmic tools are increasingly being used in the public sector to support high-impact decisions. The UK’s Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard (ATRS) helps public bodies openly publish clear information about the algorithmic tools they use and why.

???????? United Kingdom

New aspects of transparency

Intersecting with the theme of algorithmic accountability, governments are building new dimensions to their open government approaches, inching closer to visions of radical transparency and helping to build trust with citizens, which has been at a near record low in recent years (Figure 6) (OECD, 2022a). Public trust helps countries govern on a daily basis and respond to the major challenges of today and tomorrow, and is also an equally important outcome of governance, albeit not an automatic nor necessary one. Thus, governments need to invest in trust. Transparency is not the only way to achieve this (e.g. citizen engagement is also important, as discussed later in this report), but is a crucial factor (OECD, 2022b). It has assumed even greater important in recent years, as aspects of transparency enable people to better understand and comply with government actions (e.g. COVID-19 responses).

Figure 6: Just over four in ten people trust their national government

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust). Data available at https://stat.link/jlkt6v.

OPSI and the MBRCGI first explored transparency in the 2017 Global Trends report. The OECD has covered many different angles of public sector transparency more broadly, such as efforts related to Open Government, Open State, Open Government Data (OGD), promoting Civic Space, anti-corruption and integrity, as well as specialised issues including transparency in the use of COVID-19 recovery funds among others. Indeed, one of the key focus areas in the recently issued OECD Good Practice Principles for Public Service Design and Delivery in the Digital Age is “be accountable and transparent in the design and delivery of public services to reinforce and strengthen public trust”.

When looking at the latest public sector innovation efforts, two leading themes become apparent. The first is the advancement of the Rules as Code concept, which has gained significant traction in the last few years. The second is heightened transparency around the thousands of monitors and sensors embedded in daily life, the existence of which is unknown to most people.

Bringing about Rules as Code 2.0

New technologies and approaches are leading to new aspects of transparency which empower the public while enhancing the accountability of governments. One area seeing growth in innovative applications is Rules as Code (Box 7), with some dubbing the new horizon Rules as Code 2.0. While RaC offers a number of potential benefits, including better policy outcomes, improved consistency, and enhanced interoperability and efficiency (OECD, 2020a), advocates have also highlighted the importance of transparency, as RaC has made the rule-creation process more transparent in some cases, and enabled the creation of applications, tools and services that help people understand government obligations and entitlements. This can help bolster important elements of the OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (2012), which serves as the OECD’s guiding framework on good regulatory and rulemaking practices.

Box 7: Rules as Code (RaC)

Rules as Code (RaC) is a new take one of the core functions of government: rulemaking. Fundamentally, RaC proposes to create an official, machine-consumable version of some types of government rules, to exist alongside the existing natural language counterpart. More than simply a technocratic solution, RaC represents a shift in how governments create some types of rules, and how third parties consume them.

Currently, governments typically produce human-readable rules that are individually consumed and interpreted by people and businesses. Each regulated entity, for example, must translate laws into machine-consumable formats for use in business rule systems. RaC could instead see official, machine-consumable versions of these rules produced by governments, concurrently with the natural language versions. This could allow businesses to consume machine consumable versions directly from government, while reducing the need for individual interpretation and translation for some types of rules.

Source: https://oecd-opsi.org/publications/cracking-the-code.

Since OPSI and MBRCGI’s initial coverage of Rules as Code in the 2019 Global Trends report and OPSI’s subsequent in-depth primer on the topic, the concept has reached new levels of adoption by innovative approaches within government, as it begins to embed a “new linguistic layer” (Azhar, 2022) that transparently expresses rules in ways that both humans and machines can understand.

The Australian Government Department of Finance has sponsored a project that looked at how RaC could be delivered as a shared utility to deliver simpler, personalised digital user journeys for citizens. “My COVID Vaccination Status” served as the initial use case, drawing from publicly available COVID rules. The effort focused on the questions “Am I up to date with my COVID vaccinations?” and “Do I have to be vaccinated for my job?”, using a built simulator website to provide a simple, citizen-centric user journey to provide answers. This project represents a global first in use of RaC as a central, shared, open source service hosted on a common platform, allowing government offices and third parties enhanced access to information and the ability to build additional innovations on top. The project has helped demonstrate a path for scalable RaC architecture that can take this approach to new heights.

Nearby, New Zealand is rolling out an ambitious project to help people in need better understand their legal eligibility for assistance – a process that can be incredibly difficult, as the relevant rules are embedded in different complex laws. Grassroots community organisations are implementing a “Know Your Benefits” tool to address social injustice by helping people better understand their rights. The tool leverages codified rules to help citizens and residents gain access to support to which they are entitled, and to invoke their right to an explanation about any decision affecting them.

Other, additional efforts have surfaced in this space:

- Belgium’s Aviation Portal translates the vast set of aviation laws and agreements into a single online aircraft registration platform.

- The UK Department for Work and Pensions has initiated an effort to generate human and machine-consumable legislation in pursuit of a Universal Credit Navigator to clarify benefits eligibility.

- Many projects are underway in different levels of government in the United States in areas such as benefits eligibility and policy interpretation, as showcased in Georgetown University’s Beeck Center Rules as Code Demo Day.

In general, these approaches involve processes in which a multi-disciplinary team works to co-create a machine consumable version of rules which will exist in parallel with the human readable form (e.g. a narrative PDF). However, a new take on this concept provides a hint of potential future developments. The Portuguese government’s Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda (INCM – National Printing House and Mint) has created a functional prototype of laws related to retirement that applies AI to decoding laws to make them consumable by digital systems. AI can be used increasingly in this space, optimally alongside and as tools of the aforementioned multi-disciplinary teams, to accelerate the RaC movement. Like the efforts discussed earlier in this trend, such approaches should be done in a way that is consistent with the OECD AI Principles and other applicable frameworks.

However, RaC is not a cure-all when it comes to putting in place good rulemaking practices and ensuring positive regulatory outcomes. For instance, the effects of a single regulation or rule may be dependent on a range of external factors, and its scope is currently best applied to relatively straightforward legal provisions. Yet, OPSI believes that Rules as Code has the potential to be truly transformative. In addition to OPSI’s RaC primer, innovators wanting to learn more can leverage the Australian Society for Computers and Law (AUSCL)’s excellent and free series of Masterclass sessions. Those who want to start digging into the models and code can check out OpenFisca, the free and open source (FOSS) software powering many RaC projects around the world, and Blawx. Interesting personal perspectives can also be found on blogs by Hamish Fraser and Regan Meloche.

The Internet of (Transparent) Things

Smart devices and the Internet of Things (IoT) have become pervasive, yet in some ways remain invisible. There are over 11 billion IoT connected devices around the world, with more than 29 billion expected by 2030 as 5G technology continues to roll out (Transforma Insights, 2022). The potential public sector benefits are significant (OECD, 2021a), especially through the creation of smart cities – cities that leverage digitalisation and engage stakeholders to improve people’s well-being and build more inclusive, sustainable and resilient societies (OECD, 2020b). In fact, four in five people believe that IoT can be used to “create smart cities, improve traffic management, digital signage, waste management, and more” (Telecoms.com Intelligence, 2019). The research for this report surfaced several notable examples:

- Singapore’s Smart Nation Sensor Platform deploys sensors, cameras and other sensing devices to provide real-time data on the functioning of urban systems (ITF, 2020). Also in Singapore, RATSENSE uses infrared sensors and data analytics to capture real-time data on rodent movements, providing city officials with location-based infestation information.

- In Berlin, CityLAB Berlin is developing an ambitious smart city strategy, and the local government’s COMo project is using sensors to measure carbon dioxide to improve air quality and mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

- Seoul, Korea is pursuing a “Smart Station“ initiative as the future of the urban subway system. A control tower will leverage IoT sensors, AI image analysis and deep learning to manage subway operations for all metro lines.

- In Tokyo, Japan, the installation of sensors on water pipelines has saved more than 100 million of litres per year by reducing leaks (OECD, 2020c).

While research shows that the vast majority of people support the use of sensors in public areas for public benefit, and that citizens have a fairly high level of trust in government with regard to smart cities data collection (Mossberger, Cho and Cheong, 2022), IoT sensors and smart cities have raised significant concerns about “invasion of privacy, power consumption, and poor data security” (Joshi, 2019), protection and ownership over personal data (OECD, forthcoming-b, Governance of Smart City Data for Sustainable, Inclusive and Resilient Cities) as well as other ethical considerations (Ziosi et al., 2022). For example, San Diego’s smart streetlights are designed to gather traffic data, but have also been used by police hundreds of times (Holder, 2020), including to investigate protestors following the murder of George Floyd (Marx, 2022), triggering surveillance fears. Less than half of the 250 cities surveyed in a 2022 Global Review of Smart Cities Governance Practices by UN-Habitat, CAF – the Development Bank of Latin America and academic partners report legislative tools for ethics in smart city initiatives, with those that do exist being more prevalent in higher income countries.

In many cities, sensors are ubiquitous in public spaces, with opacity surrounding their purpose, the data they collect and the reason why. Individuals may even be sensors themselves, depending on their activities and the terms accepted on their mobile device. These are important issues to think about, as “democracy requires safe spaces, or commons, for people to organically and spontaneously convene” (Williams, 2021). The San Diego case mentioned above and others like it may serve as cautionary trends, for ”if our public spaces become places where one fears punishment, how will that affect collective action and political movements?” (Williams, 2021)

IoT and Smart Cities have been well documented by the OECD, with their concepts achieving a level of integration in many cities and countries that have arguably transferred them out of the innovation space and into steady-state. However, the new levels of personal agency, privacy protection and transparency being introduced to help ensure ethical application of smart city initiatives represent an emerging innovative element.

With regard to privacy protection, New York City’s IoT Strategy offers a framework for classifying IoT data into “tiers” based on the level of risk:

- Tier 1 data are not linked to individuals, and thus present minimal privacy risks (e.g. temperature, air quality, chemical detection).

- Tier 2 data are context dependent and need to be evaluated based on their implementation (e.g. traffic counts, utility usage, infrastructure utilisation).

- Tier 3 data almost always consist of sensitive or restricted information (e.g. location data, license plates, biometrics, health data).

While useful for conceptualisation, the tiers have not been adopted as a formal classification structure in government. Nonetheless, ensuring digital security is a fundamental part of digital and data strategies at both the city and country level, with some states according digital security a top priority in their digital government agenda. For example, Korea and the United Kingdom have both developed specific digital security strategies (OECD, forthcoming-b).

One of the more dynamic approaches is found in Aizuwakamatsu, Japan, which has adopted an “opt-in” stance to its city smart city initiatives, allowing residents to choose if they want to provide personal information in exchange for digital services (OECD, forthcoming-b). This represents “a markedly different approach to the mandatory initiatives in other smart cities that have been held back by data privacy” (Smart Cities Council, 2021). Though this option applies only to public initiatives, it is difficult to envision how this approach would work with smart city elements that are more passive and not necessarily tied directly to specific residents.

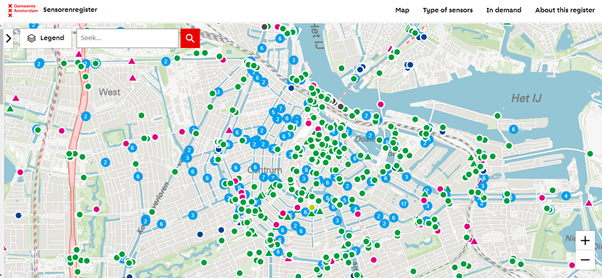

Some of the most digitally advanced and innovative governments have taken new steps to make their IoT and smart city efforts open and transparent in order to foster accountability and public trust in government. One leading effort is the City of Amsterdam’s mandatory Sensor Register and its associated Sensor Register Map, as discussed in the full case study following this section.

Other areas, such as Innisfil, Canada; Angers-Loire, France; and Boston and Washington, DC in the United States are leveraging Digital Trust for Places and Routines (DTPR) (Box 8), which has the potential to serve as a re-usable standard for other governments.

Box 8: Digital Trust for Places and Routines (DTPR)

The open-source communication standard Digital Trust for Places & Routines (DTPR) aims to improve the transparency, legibility and accountability of information about digital technology.

In 2019, experts in cities around the world took part in co-design sessions to collaborate and prototype an initial open communication standard for digital transparency in the public sphere. In 2020, this standard underwent numerous cycles of online expert charrettes and small meetings, iterative prototype development, and long-term inclusive usability and concept testing.

The final product, the DTPR, is a taxonomy of concepts related to digital technology and data practices, accompanied by a collection of symbols to communicate those concepts swiftly and effectively, including through physical signs or digital communication channels. Use of the DTPR provides a public, legible explanation of city technologies and their data footprints, enabling public input on city technologies and allowing the effectiveness of city technologies to be measured and evaluated.

Source: https://dtpr.helpfulplaces.com, www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/smart-cities-public-spaces-data.

Recent research has found that “cities today lack the basic building blocks to safeguard their interests and ensure the longevity of their smart city” (WEF, 2021). As governments continue to deploy IoT sensors and pursue smart city strategies, they should follow the lead of the cities cited above, as “public trust in smart technology is crucial for successfully designing, managing and maintaining public assets, infrastructure and spaces” (WEF, 2022). This is easier said than done, however, as governments face difficulties in establishing solid governance over such efforts – an important but often overlooked enabler of digital maturity that can help them move towards a more open and transparent approach.

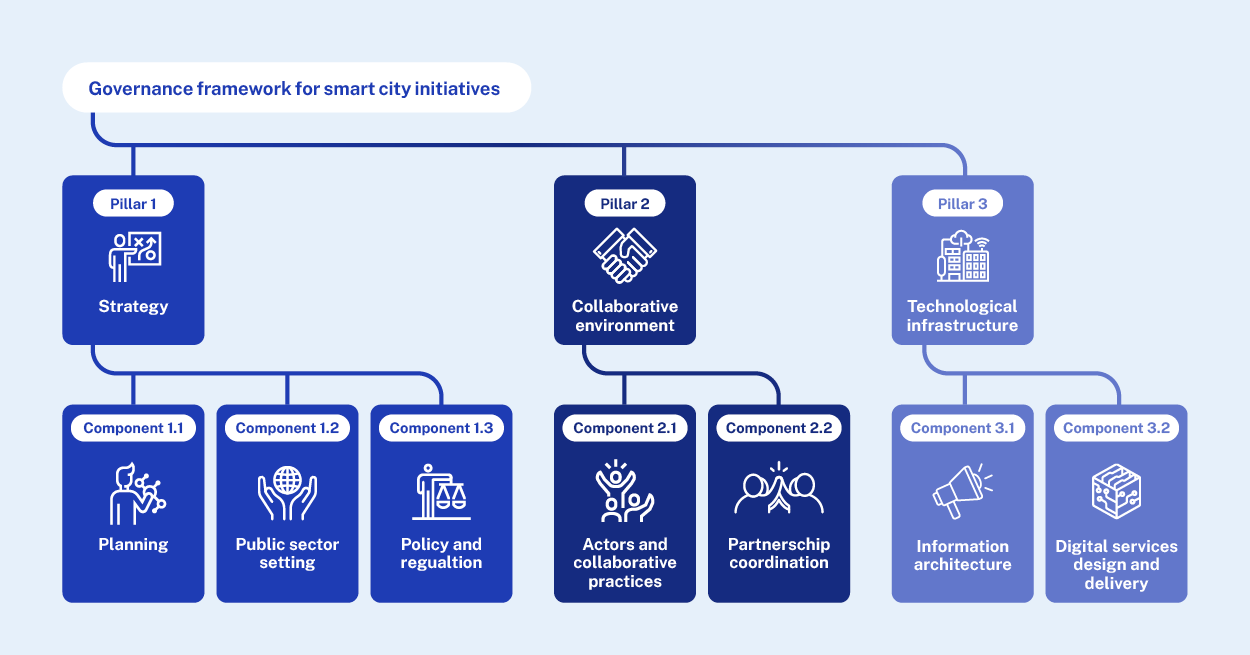

The aforementioned Global Review of Smart City Governance Practices provides a number of recommendations and a valuable governance framework (Figure 7), Pillars 2 and 3 of which include elements relevant to transparency. In addition, researcher Rebecca Williams offers 10 calls to action for cities to consider in her report Whose Streets? Our Streets! (Tech Edition). These include “mandating transparency and legibility for public technology & data” and “challenge data narratives” to ensuring “that community members can test and vet government data collection and the narratives they reinforce”, and imagining “new democratic rights in the wake of new technologies.” Ethical use of the technologies discussed in this section go far beyond transparency alone, and the guidance in these resources can provide food for thought on moving towards a more comprehensive approach with transparency as a key pillar.

Figure 7: Governance framework for smart city initiatives

Sensor Register

The Sensor Register is a tool of the City of Amsterdam used to obtain, combine and share publicly transparent information on all sensors placed for professional use in public spaces of the city. The Register is the result of an innovative Regulation which mandates the registration of all professional sensors of in public spaces.

???????? Netherlands

Institutionalising innovative accountability

The approaches discussed in the previous two themes are positive developments, illustrating how governments are connecting the concepts of innovation and accountability. Bringing together these worlds, however, has been a longstanding challenge in the public sector.

In talking with public servants anywhere in the world about innovation, perhaps the most commonly cited challenge is “risk aversion”. Many feel that trying new things in the public sector is difficult because of the negative incentives built into the system, and this sentiment can permeate the culture of government. The main issue that comes up tends to be accountability mechanisms and entities such as oversight and auditing agencies. Innovation is fundamentally an iterative and risky process. Yet, audit processes can sometimes adopt a more rigid interpretation of what risks could have been foreseen and should have been planned for. Both accountability and oversight processes sometimes seem to be predicated on the idea that a right answer existed that could have been known beforehand.

To be clear, such functions are very important for governments. They help ensure confidence in the integrity of the public sector, identify where things could be done better and create guidance about how to avoid repeating errors in the future. Like innovation, at the end of the day, accountability is about achieving better outcomes. The interplay between accountability and innovation is multifaceted but is not yet evolving rapidly enough to match the disruptive nature of new approaches and technologies in the public sector. Some governments have sought to better balance these two seeming counterweights. Back in 2009, the National Audit Offices in both the United Kingdom and Australia published guides on how to promote innovation. However, some governments are adopting a fresh perspective on accountability and putting in place processes where new ideas, methods and approaches can flourish while also reinforcing key principles of efficient, effective and trustworthy government.

One of the most systematic approaches identified for this report is the Government of Canada’s Management Accountability Framework, in particular its “Innovation Area of Management” (see Box 9).

Box 9: Management Accountability Framework – Innovation Area of Management (Canada)

The Management Accountability Framework (MAF) – a tool used by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) to monitor the management performance of federal departments and agencies – has been expanded with the integration of a new Area of Management (AoM) dedicated to innovation. Thanks to this tool, it is possible to assess a public organisation’s ability to plan, generate and use rigorous evidence to inform decision making on high-impact innovations and, in this way, support excellence in innovation management.

The assessment is carried out with a set of questions that cover the various dimensions of innovation management. By answering each question, the organisations are assigned points. The questions investigate an organisation’s ability to (1) commit resources to generate evidence to support innovation, (2) use rigorous methods of comparison to support innovation, (3) engage in innovation projects of high potential, and (4) use the evidence retrieved to inform executive-level decision making. The sum of the points scored by an organisation in each question represents a measure of the maturity level of an organisation in the field of innovation management. By collecting the results and establishing a dialogue with public organisations’ teams, TBS highlights notable work, supports the diffusion of best practices, and provides expertise and guidance to departments willing to increase their innovation management maturity.

Extensive consultations and engagement sessions were held with federal departments and agencies – the primary users of the MAF – in order to develop the Innovation AoM. This co-development proved essential to consider various perspectives, validate terminology and ensure that the approach was in line with how departments operate. The new AoM has been implemented for the first time in the 2022-23 MAF reporting cycle and will be included in future cycles to measure progress over time.

Source: https://oe.cd/maf-innovation, Interview with Government of Canada officials on 24 November 2022.

Another interesting approached is the Accountability Incubator, based in Pakistan, which seeks to infuse government with accountable practices by tapping into the potential of young people (Box 10).

Box 10: Accountability Incubator

The Accountability Incubator is a creative peer learning programme for young civic activists and change-makers who want to fight corruption and build accountability. It was developed to provide long-term support, networks and skills to people who are often overlooked by or left out of traditional civil society programmes. It is innovative in that it uses creative tools, a long-term approach and the very latest thinking to shape governance globally.

The Accountability Incubator provides tailored and hands-on support to activists and change-makers (termed “accountapreneurs”) from civil society around the world. The support they receive takes a hybrid format as useful resources are shared online and in person at Accountability Labs in eight countries – Belize, Kenya, Liberia, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The year-long programme provides accountapreneurs with everything they need – from learning opportunities to communications support, stipends and pilot ideas – to super-charge accountability within their communities and find new ways to solve entrenched problems of governance.

The overarching objective of the innovation is to build a new generation of accountability change-makers that can create a more prosperous, inclusive and fair society. So far, the project has supported over 200 accountapreneurs who have developed more than 150 new ideas for accountability. Some of these ideas include setting up the first tool to crowdsource information on public services in Nepal, establishing a film school for women to fight corruption in Liberia and building a local media outlet for verified news on issues of democracy in Pakistan.

Source: https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/accountability-incubator.

Other identified efforts have tended to focus on specific aspects bridging innovation and accountability, but with a more specific tech focus than the Canada and Pakistan cases. These include:

- The Digital Transformation and Artificial Intelligence Competency Framework for Civil Servants by UNESCO, the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which aims to promote the accountable use of innovative technology with a key focus on promoting trustworthy, inclusive and human rights-centric implementation of AI among civil servants.

- A national certification programme in Ireland to upskill civil servants on the ethical application of AI in government.

Although these efforts are positive and emit signals pointing to growing activities in the future, they remain few. More needs to be known about the relationship between relevant aspects of accountability (e.g. oversight, audit) and how they might be changed for the better. How can accountability structures (ultimately about trying to get better outcomes from government) be used to drive innovation inside public sector organisations, rather than hinder it? Is there room to respect important tenants of the audit process (e.g. independence) while also forging closer ties and partnerships between oversight functions and those that they look over? How can new forms of accountability that integrate users into the processes of monitoring and assessing public actions (e.g. participatory audits) drive innovation in government?

Little work has gone into answering these questions, signalling the need for deeper research and analysis at a global level. The OECD Open and Innovative Government Division (OIG) is exploring avenues to fill this gap and expand upon this field of study.

Although not discussed as a specific sub-theme in this report, it is important to note that leveraging innovative approaches to transform accountability, oversight and auditing functions themselves is also an area ripe for deeper analysis, as discussed by the OECD Auditors Alliance. Some examples of this include Chile’s development of a data-driven Office of the Comptroller General (CGR), as well as the creation of accountability innovation hubs and labs in Belgium, Brazil, the Netherlands, Norway, the United States and the European Court of Auditors (Otia and Bracci, 2022).

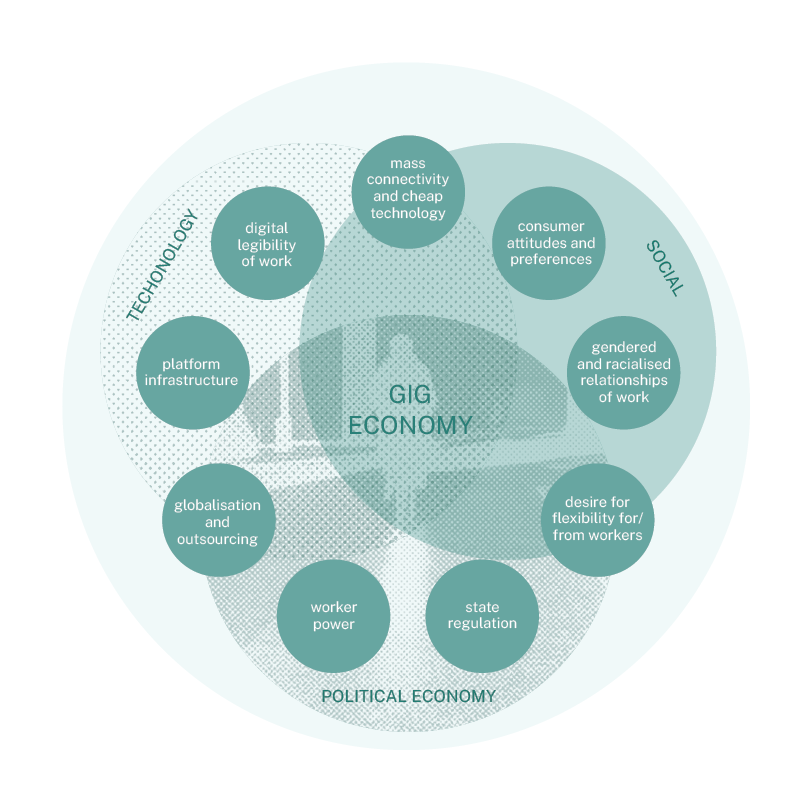

Trend 2: New approaches to care

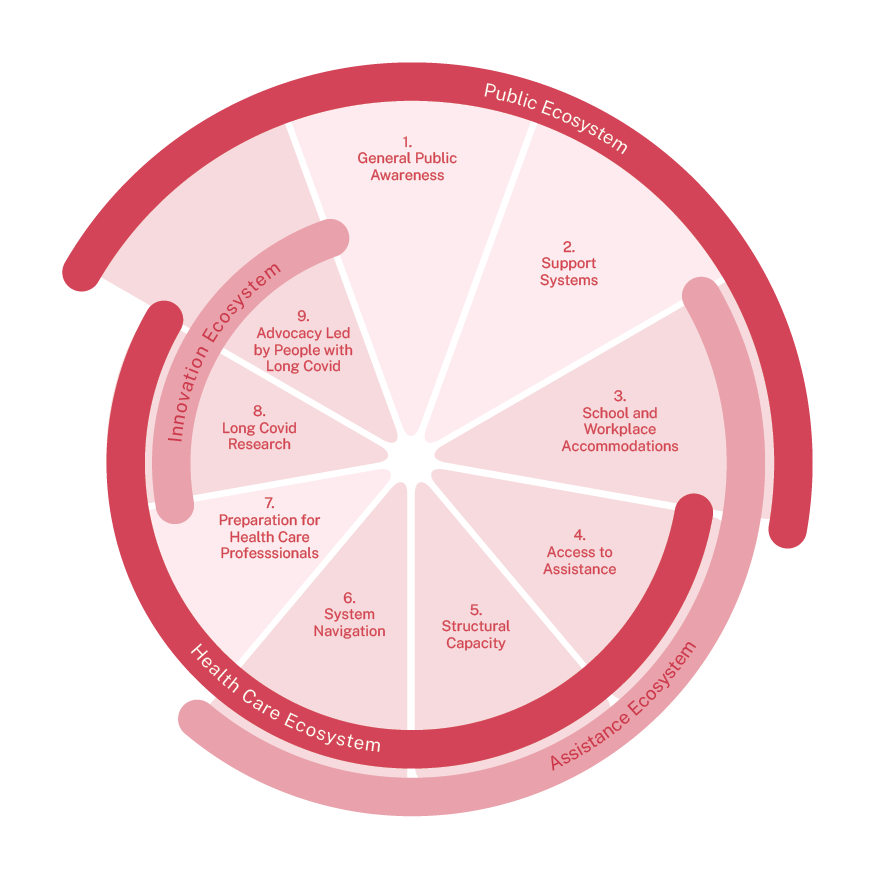

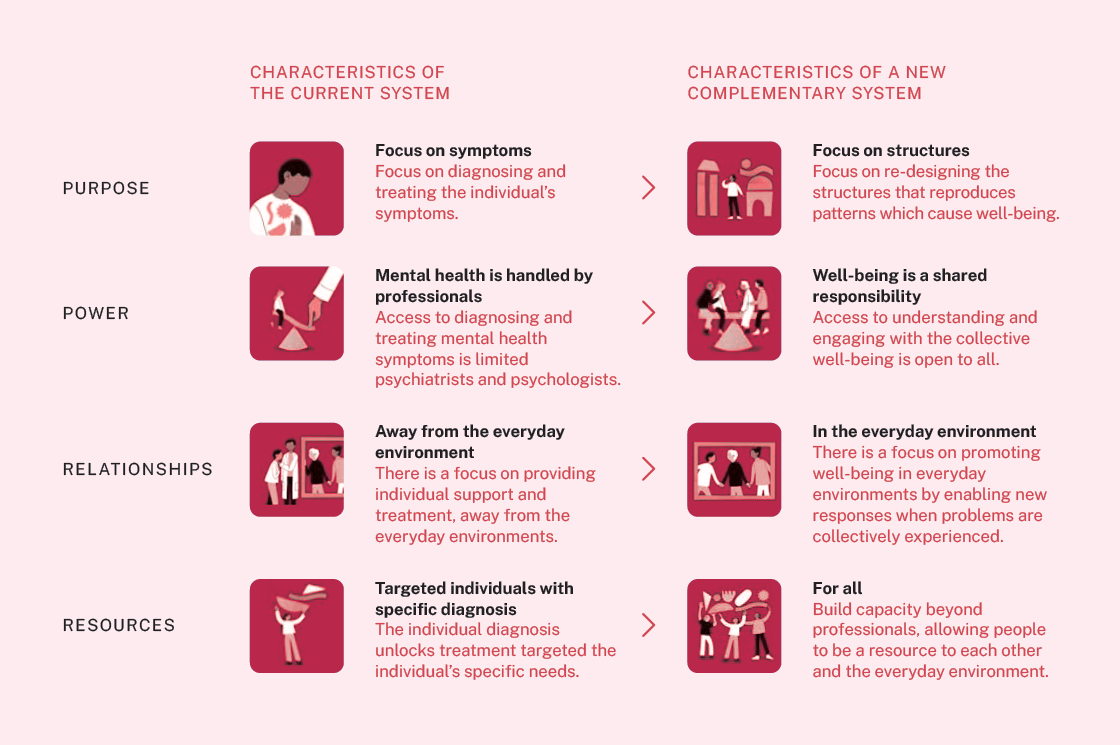

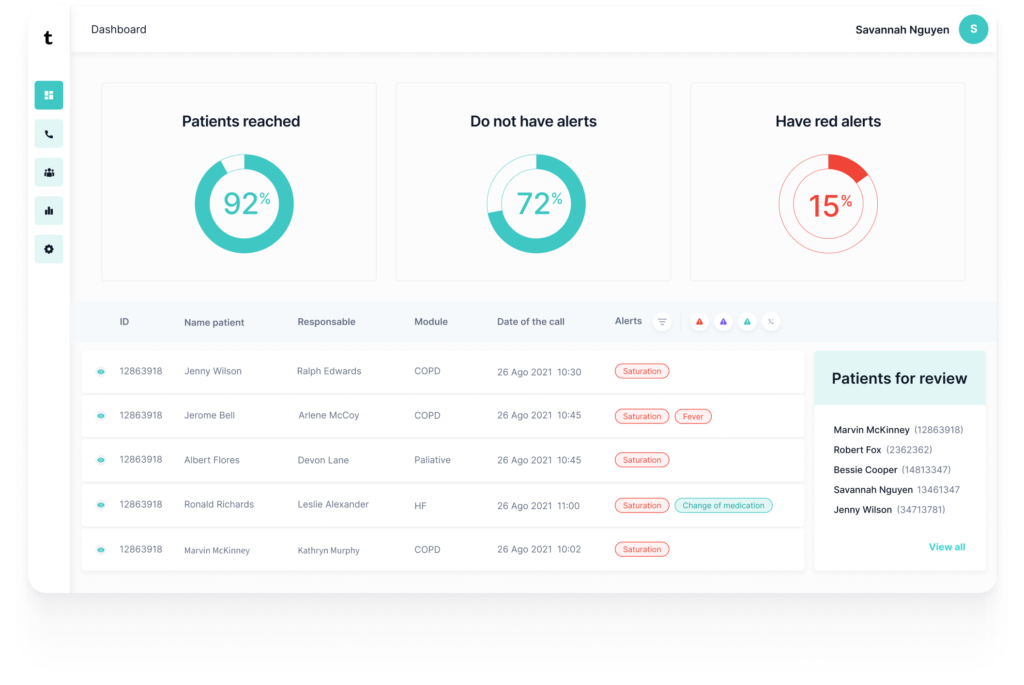

The COVID-19 pandemic placed care services under the spotlight with rapid scaling of technological innovations, especially for healthcare at a distance. However, global population trends, notably aging and growth in chronic diseases, necessitated a change in approach even before the crisis. In the face of increasing demand, disjointed health systems have prompted calls for more people-centred, integrated approaches. Such systems can also yield better quality data to drive improved outcomes, enabling governments and other health systems to make use of emerging technologies to better understand patients and diseases. This requires a shift towards systems approaches, re-orienting government processes and data flows. OPSI and the MBRCGI also found a strong innovation focus on mental health – a major casualty of the recent pandemic – leveraging methods such as Behavioural Insights. Finally, the most powerful tool for revolutionising care seen in this cycle of work is Artificial Intelligence (AI), with powerful solutions coming from governments, GovTech startups and nonprofits, though hurdles to progress remain, including insufficient data and infrastructure and absence of agreement on tailored principles for ethical and trustworthy use of AI in healthcare.

Re-orienting care (eco)systems

People generally require different types of care at different times and points in their lives. In addition, issues like aging populations and increase in chronic diseases are shifting the focus of healthcare delivery beyond acute hospital care. For instance, almost two in three people aged over 65 years live with at least one chronic condition often requiring multiple interactions with different providers, which makes them more susceptible to poor and fragmented care. Such fragmentation has prompted calls for making health systems more people-centred, and has fuelled debate about the need for integrated delivery systems capable of continuous, co-ordinated and high-quality care delivery throughout people’s lifetimes (Barrenho et al., 2022).

In recent years, governments have introduced integrated care, holistic approaches aimed at ensuring individuals receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time, but existing organisational and financing structures appear to hinder their success. In general, healthcare systems remain fragmented, focused on episodic acute care and unsuitable to solve complex health needs (Barrenho et al., 2022). Even within the same country, systems are highly unequal across regions and cities (OECD, 2022c). The COVID-19 pandemic has also amplified the need for various parts of the health systems to work together to deliver seamless care and to ensure clear co-ordination across levels of government (OECD, 2021b; OECD 2021c). In addition to these integrated systems approaches, governments can also drive progress through innovation in how they leverage and activate all relevant actors in care ecosystems able to contribute to promoting health and wellbeing (Deloitte, 2022; Pidun et al., 2021).

The research and Call for Innovations conducted by OPSI and the MBRCGI returned a number of interesting and innovative projects that demonstrate the re-orienting and strengthening of care systems and ecosystems through systems approaches (Box 11).

Box 11: Systems approaches

Complexity is a core feature of most policy issues today, including care, yet governments are ill-equipped to deal with the range of uncertain and complex challenges whose scale and nature call for new approaches to problem solving.

Such approaches analyse the different elements of the system underlying a policy problem, as well as the dynamics and interactions of elements that produce a particular outcome. The term systems approaches denotes a set of methods and practices that aim to affect systems change. Drawing on holistic analysis, they focus on the impacts and outcomes of policies, going beyond the linear logic of “input-output-outcome” of traditional approaches to policy design. This is achieved by involving all affected actors inside and outside government, and leaving room for iterative processes to account for uncertainty.

These approaches are distinct from traditional approaches which address social problems through discrete policy interventions layered on top of one another. Such approaches may shift consequences from one part of the system to another, or address symptoms while ignoring causes. Conversely, looking at the whole system rather than the individual parts enables one to identify where change can have the greatest impact.Source: https://oecd-opsi.org/publications/systems-approaches.

Re-orienting systems elements to provide integrated solutions

A number of the public sector innovation initiatives reviewed by OPSI and the MBRCGI focused on citizen-centred approaches to care that change the way services come together. Rather than requiring citizens and residents to go to different organisations and offices based on the functional structures of government, government absorbs this burden and provides holistic services that meet people where they are. One of the most compelling and innovative cases in this area is the Bogotá Care Blocks, presented as a case study later in this trend.

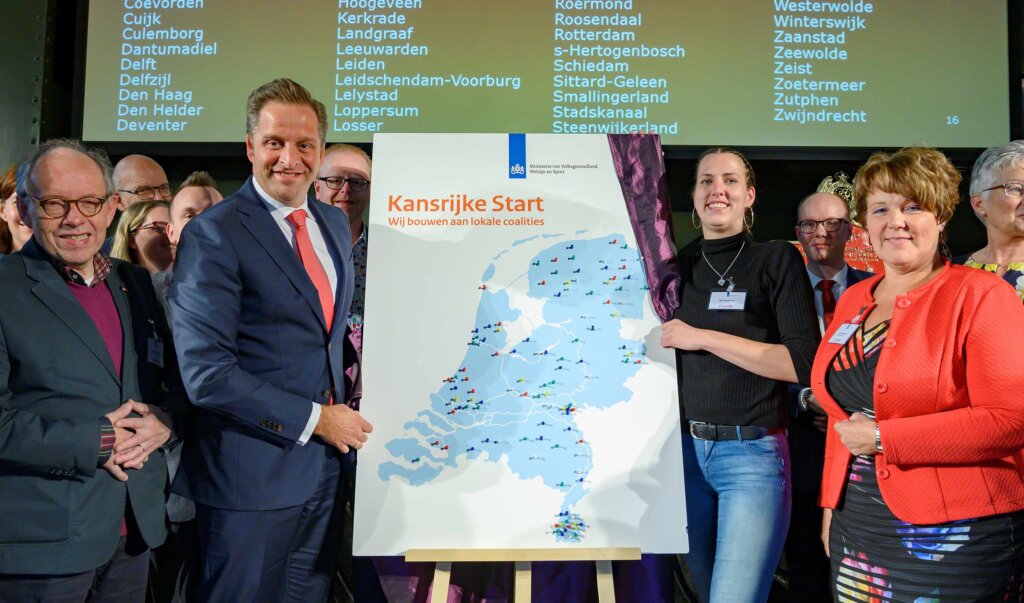

Another example – and perhaps one of the strongest proven leaders in this area – is Solid Start, a collaboration among cities, civil society organisations and the Dutch government. Launched in 2018, it seeks to ensure that every child in the Netherlands has the best possible start to life and the opportunity of a good future. As of early 2022, 275 of 345 Netherland’s municipalities have built “integrated, multisectoral teams – local coalitions – that [have] brought together service providers working in both the health-care and social domains” (Innovations for Successful Societies, 2022) to support children’s first 1 000 days.

Figure 11: Dutch Minister Hugo de Jonge showing a map of the Solid Smart municipalities

Another relevant example is the Plymouth Alliance Contract, which supports people with complex needs in the United Kingdom. Traditionally, contracts were “commissioned in separate silos, often resulting in duplication, inefficiencies and poor outcomes for the person using multiple services.” Under the co-produced Alliance mode, a legal partnership agreement created by the City Council, “25 contracts spanning substance misuse and homelessness were aligned” (E3M, 2021). Benefits include a range of newly developed practices that are co-operative and focused on the full system, treating more people, better and for less money (Wallace, 2021). A more focused discussion on affordable housing and homelessness can be found in Trend 3.

I can’t remember how I found my way – who referred/sent me. What I do know is it wasn’t just life changing, it was lifesaving. Slowly but surely, I began to feel safe, I began to trust someone. Within less than a year I have made giant leaps forward. I am forever grateful for the opportunities given to me.

Testimonial from a Plymouth Alliance service user (source)

In Scotland, the Healthcare Improvement Hub (“ihub“) adds an additional layer to re-orienting, this time by focusing on building a human learning system using anticipatory innovation principles (see the Centre for Public Impact for more research on this field). While most systems approaches identified for this work focus more specifically on the challenges of today (or are still responding to the challenges of yesterday), ihub seeks to build crisis response and anticipation into Scotland’s healthcare system, while adopting a systemic approach to innovation that supports long-term improvements. ihub tests, evaluates, shares, understands, adapts, assesses and evaluates the sustainability of findings and solutions for long-term improvement based on a four-step process:

- Crisis response and initial reaction management.

- Adaptation to the crisis.

- Transition phase to emerge from the crisis.

- Building new realities and learning from the crisis.

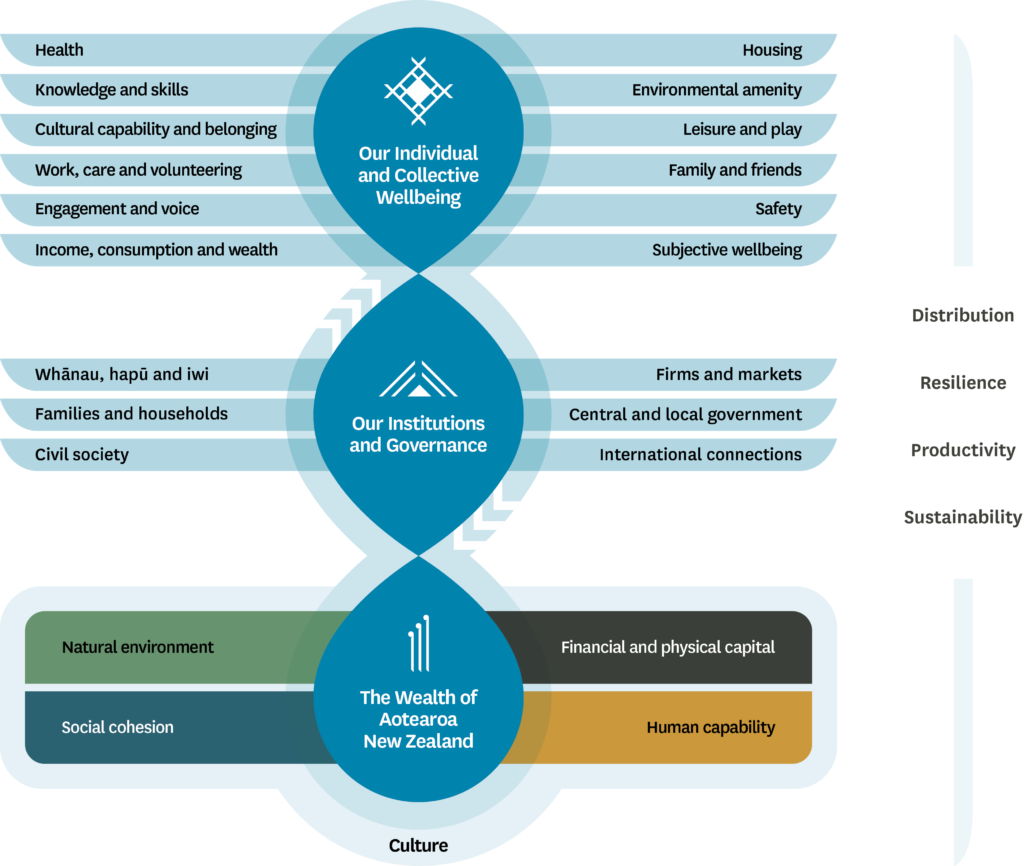

To be able to re-orient systems in innovative ways, governments need to acquire a fuller perspective of the complexities and activities of their systems, as well as how these align with positive health and wellbeing for their people. In New Zealand, the Treasury’s 2021 Living Standards Framework (LSF) aims to help government understand interdependencies and trade-offs across the different dimensions of wellbeing in order to align government activities to achieve improvements in this area. It focuses on three levels, as captured in Figure 12. In the words of Caralee McLiesh, Chief Executive and Secretary of the New Zealand Treasury, the LSF “requires us to look beyond measures of material wealth and consider human, social and natural capital, broader wellbeing outcomes, risk and distribution”(CPI, 2022).

Figure 12: The Living Standards Framework

As with many forms of public sector innovation, data is a critical factor. Integrated systems can yield better quality data to drive better outcomes, and likewise, better use of data is increasingly critical to providing integrated systems approaches to care – as recently highlighted by the former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Research (Seastedt et al., 2022) shows that bringing together different types of data can promote fairness and enables governments and other health systems to make use of emerging technologies such as Machine Learning to better understand patients and diseases (see the “New Technologies” section of this trend). Furthermore, it is possible to achieve this goal and still protect privacy and avoiding issues such as bias. Yet, the pandemic has demonstrated the major weakness of health data systems, with data trapped in silos (Smith, 2022).